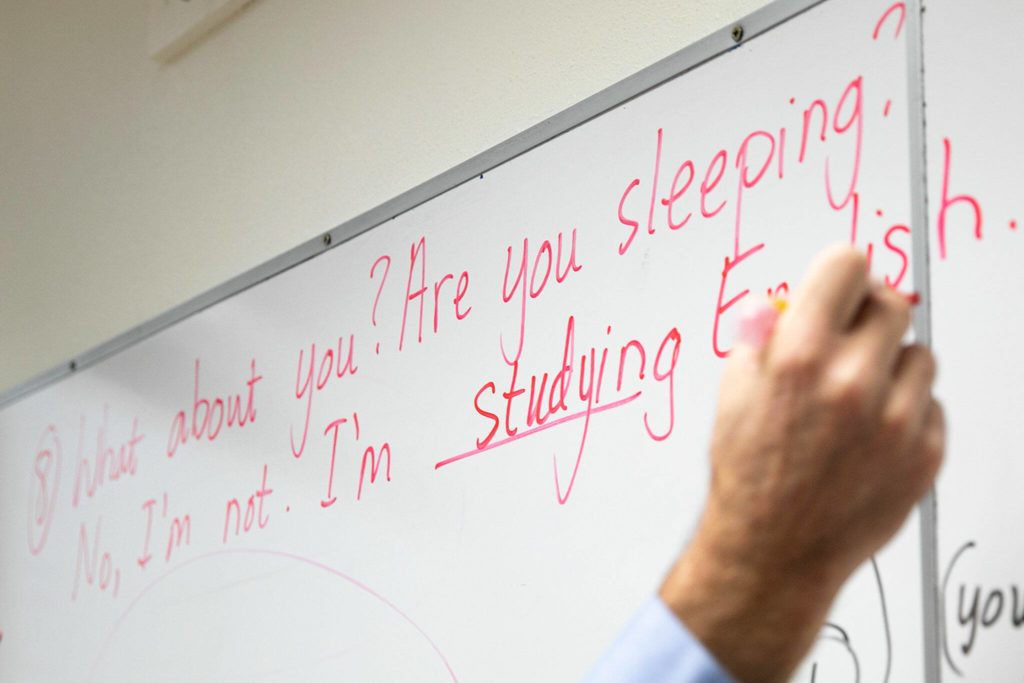

EVERETT — Students scratched foreign characters on paper Monday as a red Expo marker squeaked out bits of English on the whiteboard at Everett Community College.

In the second row, a spry 70-year-old music teacher from Ukraine smiled attentively. It took her a month of travel — on trains, planes and cars in Latvia, Poland, Germany, Mexico and finally the United States — before she arrived in Everett in May.

“My name is Liudmila. I am from Ukraine. … Please speak slowly,” she said, laughing. “I’m learning English because I live in America now,” Siri translated for her.

Her Beginner’s English class of 28 students is three students over capacity. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine uprooted millions of people, demand has boomed for English classes. This is one of 15 offered at Everett Community College — free of charge.

Professor James Willcox teaches Liudmila’s 16-credit class for four hours a day Monday through Thursday.

“I’ve had Iranian, Iraqis, Syrians, because it depends on where the hot spots in the world are,” Willcox said. “But most recently there’s just been this tidal wave (from Ukraine), of course.”

Snohomish County is home to 1,905 Ukrainian refugees, and it ranks as the 16th most populous county in the United States for people fleeing the Russian invasion, U.S. Rep. Rick Larsen, D-Everett, said earlier this month. So every weekday, hundreds of Ukrainian refugees gather to muddle through the syntax of a language very different from their own.

Liudmila’s daughter and grandchildren moved to Everett. Liudmila, a refugee who asked to be identified only by her first name, found a home in Lynnwood. She was proud to share that her daughter is enrolled in the third-level English course.

“My entire family is student,” she said, grinning.

Van Dinh-Kuno, the executive director of the Refugee & Immigrant Services Northwest, stressed that English language lessons are essential for quality of life. These people lost their homes and may have lost loved ones. They now live nearly 9,000 miles away, surrounded by people they cannot speak with. She explained that incoming refugees are assessed in reading, writing, listening and speaking before being divided into corresponding classes.

Teaching English to refugees poses different challenges than teaching English to, say, a study abroad student, Willcox explained. Refugees aren’t on scholarships with family back home; they are actively caring for children and loved ones, and their ability to learn English affects their likelihood to get a job and earn money.

“The more English my clients have, the more money they make,” Dinh-Kuno said.

Dinh-Kuno herself fled a war-torn country, Vietnam, and arrived in the United States when she was 16 years old.

“As a refugee, I had 20 minutes to pack my bags and run for my life. We were in a boat for 11 days — no food, no water,” she said.

Initially, she stayed at a camp in Arkansas. The First Lutheran Church of Brainerd, Minnesota, offered her and her 11 siblings sponsorship.

“Every single one of us finished college in this country,” said Dinh-Kuno, who earned a degree in biochemistry from the University of Minnesota and worked as a researcher before transferring to Everett.

The Ukrainian refugees arrive in Snohomish County on “humanitarian parole status” and have to immediately apply for Temporary Protected Status. The status lasts 18 months, and they must pay $500 for a work authorization card before they can get jobs. People then either apply for an extension or for asylum, a process that can take two years to be accepted or denied. If accepted, people can apply for a green card, and then they must wait five years before taking a test to become a U.S. citizen.

In all, the process can last 15 years.

Elvira Nazarova, the billing specialist for Refugee & Immigrant Services Northwest, helps refugees with these applications. All of the Ukrainians enrolled in English lessons want to apply for citizenship eventually, she said.

Nazarova gestured to a stack of manila folders, each inches thick with paperwork, teetering in the corner of the office. Then she pointed to another stack. And another — all corners crowded with columns of applications for hundreds of people.

“I need a new file cabinet,” she said, shaking her head.

Nazarova emigrated from Uzbekistan through the Diversity Visa Program, or as most people say, she “won the immigration lottery.” In the program, people from countries with low immigration numbers to the United States can apply for visas. A small number get randomly selected.

“It is exciting because I got it — I got lucky,” Nazarova said. “Many people apply, and most of them wait many years.”

She now uses her own fortune to help others achieve the same dream of citizenship.

Willcox, an immigrant from England, has been teaching English to refugees for 10 years. He met his wife, who is from Edmonds, while studying abroad in Oregon.

“It’s just wonderful,” Willcox said. “Religion, race and all those things can go out of the window. We’re just here studying English and getting on and talking. I absolutely feel that it’s a privilege to meet and engage with people from so many different nationalities. It feels like it’s good work.”

He nodded to the front row, gesturing toward two women in conversation.

“I mean Sami (from Afghanistan) has made such good friends with Diana from Colombia,” Willcox said. “The cultural exchange is something I love, and I think these guys really enjoy it, too. We’re having a good time.”

The lessons teach language as well as basic computer skills and cultural knowledge. They help refugees build a new life, create community and integrate into their new society.

“I like America,” Luidmila said, smiling. “And I like English. It’s very nice.”

More information about resources can be found at the website for Refugee and Immigrant Services Northwest, a nonprofit headquartered at EvCC. Donations are accepted in Rainier Hall, Room 228.

Kayla Dunn: 425-339-3449; kayla.dunn@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @KaylaJ_Dunn.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.