EVERETT — Since the killing six years ago, Anthony Garver has lived in legal limbo, shuttling between jail and a state mental hospital as psychologists over and over found him too mentally ill to stand trial.

On Tuesday, after a month of trial, a judge found Garver guilty of murdering Lake Stevens woman Phillipa Evans-Lopez, 20. The killer gagged her, slit her throat and stabbed her more than 20 times in June 2013.

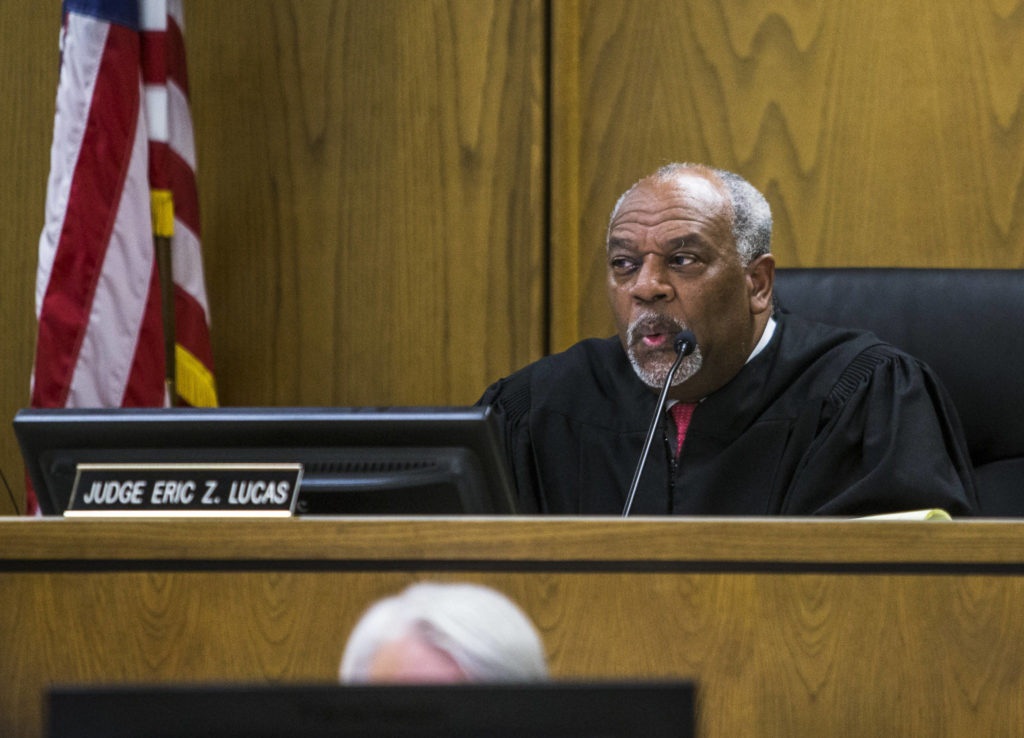

Garver, 31, whispered back and forth with his attorney after he was led into the courtroom Tuesday. Superior Court Judge Eric Lucas delivered his verdict to a packed courtroom. He said he believed Evans-Lopez had been tortured by Garver for days.

Lucas found the defendant guilty of first-degree murder with a deadly weapon.

Garver had given two stories about what happened — one at the time of his arrest, and another at trial — and neither could be believed, Lucas said.

Last week the defendant took the witness stand and denied any part in the crime. He conceded what he could not deny, that security cameras showed him and Evans-Lopez at a Walmart in Everett, then at a McDonald’s in Lake Stevens, in the early morning of June 14, 2013. A bail bondsman reported finding her dead three days later, in an upstairs bedroom of her boyfriend’s home.

The boyfriend, Lance Cleator, was in jail at the time on a driving-related warrant.

On the witness stand Garver claimed he’d known Evans-Lopez for months. He met her at a bus stop, he said, and sometime in the weeks before she died, she gave him a folding knife with a blue hinge — what prosecutors believe was the murder weapon. A state crime lab found Evans-Lopez’s blood in a groove of the knife. Garver’s defense attorney, Jon Scott, argued it may have been contaminated as the state lab examined different pieces of evidence in the case.

Garver testified he’d gone to the Lake Stevens house with Evans-Lopez. He said he simply left after a few minutes. He claimed he didn’t go upstairs, where the woman’s body was found days later, with limbs outstretched and tied to the posts of the bed.

Police caught up to Garver soon after a state lab found his DNA on an electrical cord used to bind one of the woman’s wrists. He had a felony record, and his genetic profile was in a national database. He was arrested July 2, 2013, in Everett. In an interview with a sheriff’s detective, he claimed to be his brother. At trial he testified he’d lied about many things in the 2½-hour questioning because he did not want to go back to prison for violating probation.

At least six times early in the case, state psychologists opined that Garver was unable to assist in his defense. The case was briefly dismissed while he was civilly committed to Western State Hospital.

He escaped from the mental facility around 6 p.m. April 6, 2016, with one of his roommates. Defeating the lock on the secured window “surely took weeks,” according to court records. Garver took a bus across the state to his hometown of Spokane, where he was captured. The breakout led to heightened scrutiny at Western State and the firing of the hospital chief.

Garver’s condition fluctuated when his medication dosages changed, or when he refused to take drugs.

“Every time I stop taking the medications I become psychotic … (and) start hearing voices and seeing colors,” he reported in 2017.

Garver had a well documented history of “thought disorganization, incoherent speech, impaired attention, behavioral dysregulation, suicidal and homicidal ideation, aggressiveness, response to internal stimuli, paranoid ideation, grandiose beliefs, delusional thought content, flat affect, impaired grooming and hygiene, and thought blocking,” wrote a forensic psychologist in one of many reports.

As early as age 13, doctors expressed concerns that Garver “presented a likelihood of serious harm to others,” according to forensic mental health reports. He’d been obsessed with gas masks, chemical warfare and conspiracies, and had been overheard making threats to carry out an attack with an automatic weapon. He talked about burning his hands so there would be no fingerprints.

In 2002, a doctor noted that Garver had “intrusive thoughts,” including, “I want to kill my brother with a knife.” A report from 2003 said he’d threatened to make a bomb to blow up his school.

His mental health struggles continued into adulthood. By 2006, he’d been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and unspecified psychosis.

He was sentenced to a year in federal prison in 2009, for possessing ammunition for an AK-47 after being committed to a mental institution. He was on probation when he arrived in Everett in 2013. Behind bars on charges of murder, Garver claimed aliens and demons had told him to destroy mankind, according to mental health reports.

“I have telepathy, telekinesis and mind control,” he reported in January 2017. “I am God.”

Over the years, jail and medical staff documented many threats of violence by Garver.

“I am going to walk out of here and there will be casualties, starting with the first person who opens this door,” he said in February 2019, according to a mental health professional’s report. “I … have addresses and information and can get more. You don’t believe me? I’m going to do something and I have the means to do it.”

At least one doctor concluded the evidence showed Garver was exaggerating some of his psychological issues, to avoid legal consequences. However, the doctor found he did appear to have a genuine mental illness, marked by a “constellation of symptoms.”

Judge Lucas signed an order this year requiring Garver to take his medication, if he refused it. Over the months that followed his mental state stabilized, and he was found competent to stand trial in July.

A bench trial began this month in front of Lucas. The judge recited his interpretation of the facts to the courtroom for about an hour Tuesday, listing off which witnesses he’d found credible and which he did not — ending with Garver.

Twice in court, the judge had watched the recorded interview between the suspect and the detective. The judge said he saw an intelligent, combative young man who was confident in his intellect but delusional in his tactics to deflect guilt.

“I did not see any sort of debilitating mental illness,” Lucas said. “Intellectually he is more than a match for the detective.”

The judge, who is black, said it appeared Garver had chosen to fulfill homicidal fantasies by killing Evans-Lopez because she was “a black, drug-addicted tiny female that no one cares about because they are black.”

“She fit everything he was angry at,” Lucas said.

Garver may have figured drug dealers would be the prime suspects, not a silent killer, Lucas said.

Evans-Lopez’s mother, Kris Evans, had expressed hope that a trial would finally bring closure. Instead the family was forced to relive the pain of six years ago.

“I realized that first day that I came (to court), it wasn’t going to be the magic that I thought it was going to be,” she said Tuesday.

But she’s glad, she said, that there will be justice for her daughter.

Less than a week before she died, Evans-Lopez told her friends on Facebook that she was trying to get life straightened out for the sake of her young son, Kris Evans said.

“If she’d used her drive and headed in a different direction, she could’ve been running a company or something like that,” the mother said. “She could’ve done anything she wanted.”

Sentencing is scheduled for Nov. 6.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.