Sylvia and Don Irvine became foster parents in the mid-1980s for personal reasons. A 12-year-old stepdaughter of Don’s wanted to come live with them. More than 32 years and 250 kids later, what the Lake Stevens couple learned about children they housed and helped is shared in a new book.

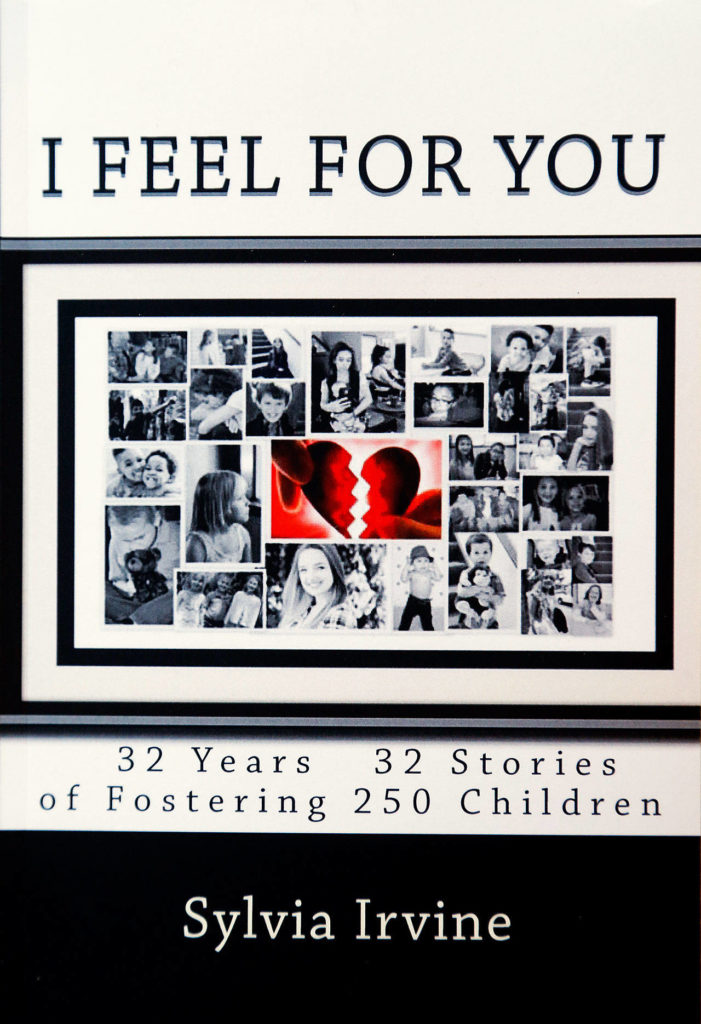

“I Feel For You: 32 Years 32 Stories of Fostering 250 Children” is the title of Sylvia Irvine’s nonfiction book. The author changed kids’ names in the self-published book, and for chapter headings used photos of volunteer models rather than pictures of their foster children.

Her accounts of foster parenting span a roller coaster ride of experiences, heartwarming to harrowing. The Irvines don’t have children in their home now, but remain licensed foster parents with the state Department of Social and Health Services. A phone call asking them to help a child could come any time.

Norah West, a DSHS spokeswoman, said state records show the Irvines being licensed back to March 1986, “and they are still, with an active license in good standing.” Records also show the number of placements in their home aligns with the 250 noted in the book, West said.

The opening pages list emotions foster children shared over the years. They include: “You say you feel alone and nobody loves you.” And “You feel sad that your parents chose drugs over you.”

“I sat and listened,” said Sylvia Irvine, who years ago directed a kids’ performing troupe called Sunshine Generation. She has volunteered with Christmas House, and in 2007 was honored by the Greater Lake Stevens Chamber of Commerce as its Citizen of the Year.

Now 64, she was born in Honduras. She came here as a child, and now teaches Spanish in her home. One chapter tells how she and her husband searched for the birth mother of a foster child who’d been adopted from Honduras as an infant.

That foster daughter was an adult when she asked them to help search for her roots. They couldn’t find the birth mother, but 22 years after that child first came to their home they are still in touch with her.

They have seen successes among kids who stayed with them. “I’d drive them to school,” said Don Irvine, 67, who is retired from the now-closed Bayliner boat-building plant in Arlington. “Eight kids graduated from high school and three went to college.”

Some foster children wreaked havoc in their home, where the Irvines also raised their own three kids.

One chapter describes a defiant 10-year-old who had victimized his siblings. In their home, he was often caught kicking their dog and harming their cat. Irvine felt sorry for him. “His only way of showing his emotions was to have a behavior of hurting animals,” she said.

Another boy, a 4-year-old, started a fire in their home, they said.

In recent years, they have housed hard-to-place teenagers.

Calling her last chapter “kind of dramatic,” Irvine recalled a 15-year-old girl who was to stay only one night before going to a group home. Irvine wrote that when they got up the next morning, a family car and the teen were gone. The girl was arrested in south King County. Driving Irvine’s SUV, she had been chased by police and hit several cars.

Irvine said the teen’s mother had died a month before of a drug overdose. “Kids do all this stuff because of what they’ve gone through,” she said.

The Irvines, who made 16 family trips to Disneyland and included their foster kids, said they have tried to do something special for each child.

West, the DSHS spokeswoman, said Washington has about 5,000 licensed foster homes, and roughly 9,200 children in care out of their own homes. Many are with relatives who aren’t licensed foster parents. “The need is great, especially for homes that can care for sibling groups, older youth, and children with health and behavioral challenges,” West said.

The Irvines have cared for kids from Pasco and beyond. They supported several young people into adulthood. Along with training, a foster parent must undergo a home inspection and background check. The state provides reimbursements to help with costs.

“You don’t do it for the money,” Sylvia Irvine said. “They have a lot of problems and issues. You’ve got to have a lot of patience.”

One foster daughter, who returned to them several times, had a baby at 15, and kept her child. Another foster child had ties to a gang. After they reported one runaway, Irvine recalled, a Lake Stevens police officer suggested they stop taking in kids — and that kids are getting worse.

“You can’t give up on these kids who need you,” she said. “We didn’t give up. They were part of the family the minute they walked in the door.”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

Learn more

Sylvia Irvine’s book, “I Feel For You: 32 Years 32 Stories of Fostering 250 Children,” is available on Amazon.com in paperback ($15.99) or ebook ($9.99) formats.

Information about becoming a licensed foster parent in Washington: www.dshs.wa.gov/CA/fos/becoming-a-foster-parent.

More information: http://fosteringtogether.org.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.