BOTHELL — On a rainy January morning, Clara Bannon led her school’s weekly meeting.

About 30 students and four staff members sat in a loose circle.

“All in favor raise your hand,” said Clara, 15.

“What are we voting about?” a student asked.

“If you were listening you would have known,” Clara replied. “We are voting to approve (The Daily Herald) to observe our school meeting.”

As Clara counted hands, the student replied: “Oh, sorry, my brain froze.”

At The Clearwater School north of Bothell, the voices of students and staff are equal. One person, one vote — whether it’s a 5-year-old or the school’s founder, Stephanie Sarantos.

The Daily Herald put the school’s direct democracy model into action recently. Before a reporter could come to Clearwater, students debated whether to allow the visit. After three meetings and conversations with staff and students, the school voted to let the reporter in.

Clearwater, founded in 1996, is part of a loose network of about 45 schools following the Sudbury model of direct democracy and student-controlled learning. It’s the only accredited school in the state using the model. Almost three decades later, it still feels like a radical reimagining of what a school is supposed to do.

This year, the state Department of Commerce approved a $136,900 grant for Clearwater to explore opening a bilingual preschool based on the alternative education model.

Each day at Clearwater, the 60 enrolled students choose their own lessons. They make music; work, play or program on the computer; rehearse a peer-produced play. The kids range in age from 4 to 19. There are no curricula, classes or tests.

A student-led justice committee decides how to resolve conflicts. Adults on campus are “staff,” not teachers. They only help if asked. Staff do administrative work. They also mentor the students and sometimes organize classes. They, too, are voted in each year.

At the weekly meeting, the only mandatory event, Clara rushed through a list of announcements: plans for a pizza party, news about a potential foosball table donation and the talent show that afternoon.

Some students engaged with Clara. Others stared at their screens. It wasn’t too far from what you might see at any city council meeting, with a roomful of adults.

Lily, a student organizing the talent show, asked last-minute performers to see her after the meeting.

“It’s going to be super fun,” she said. “You also get free food at the end of it if you sit through it.”

‘All your energy into it’

The first school of this kind opened in Sudbury Valley, Massachusetts, giving the model its namesake in 1968. Most Sudbury schools using the model are in the United States, with a handful in Japan, Israel and Germany.

Former Clearwater student Gabriel Klein, now on the staff, said the model fosters self-motivated adults.

“Having the choice to do what you want to do means that, when you’re choosing to do something, you’re going to show up there, and you’re going to put all your energy into it,” he said.

Few studies have looked into the post-graduation outcomes of Sudbury students. A 1986 review in the American Journal of Education surveyed 69 graduates of the original Massachusetts school. Just over 50% of the participants had a college degree or were enrolled in secondary school. Half of the group said attending Sudbury was a hurdle to higher education. They also said the benefits outweigh the disadvantages.

At Clearwater, students choose when they graduate, though their peers do vote on it. College isn’t always a metric for success. Even so, school data shows about 70% of Clearwater graduates pursue higher education. Several staff members said Clearwater education mirrors adult life more closely than traditional school, teaching self-motivation and time management. This is helpful in college — and in life.

Anecdotally, Klein said, many student choose careers in theater, the arts and English. Other graduates have studied public health, urban design or computer science. At least one went on to law school.

But the sample size is too small to identify any clear trends. Many of the students come from college-educated families.

Tuition is $10,300 a year. According to Private School Review, that’s more expensive than the average private school in Snohomish County ($8,532), but cheaper than average tuition in King County private schools ($19,599). Sarantos said many students are on financial aid.

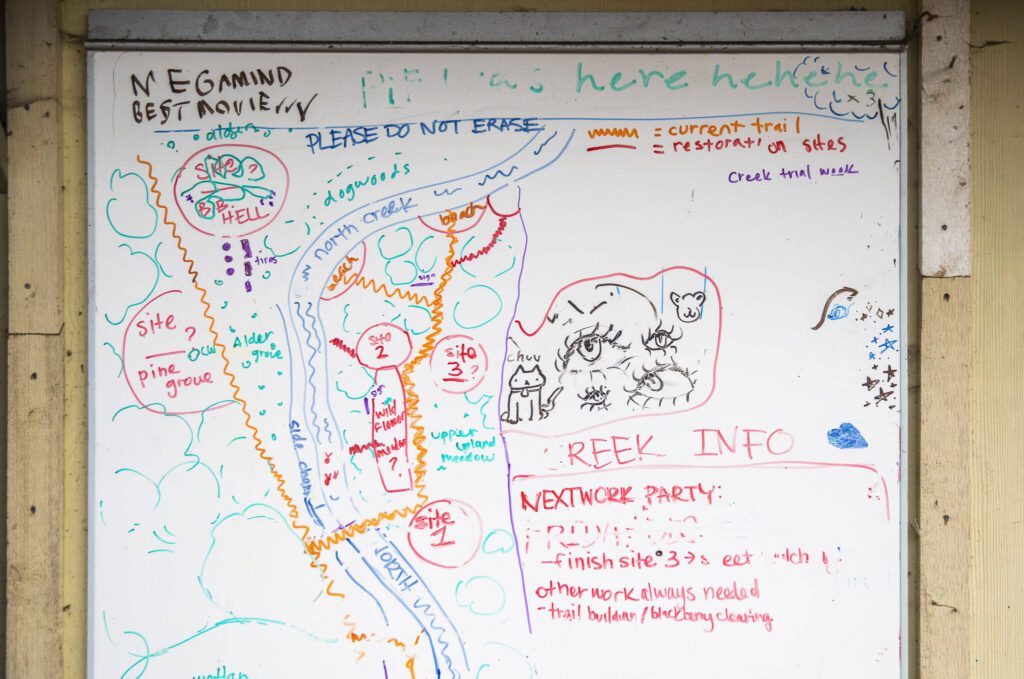

Clearwater’s 3½-acre campus at 1510 196th St. SE spans five buildings that house a computer lab, gym, kitchen, common room, art room and office, just west of Bothell-Everett Highway. Outside, the children can hang out on the playground — complete with a few benches and a donated landlocked boat — or stroll alongside the nearby North Creek.

‘There’s more buy in’

Sarantos first worked as an oncology nurse, caring for families and kids with life-threatening illnesses.

As her son grew up, she realized he didn’t fit in a traditional preschool. So she started an informal preschool with a group of friends. They set up traditional activities but realized the children were learning on their own.

At the University of Washington, Sarantos earned her doctorate in educational psychology, with specializations in special education and cognitive development.

She dreamed about an education that would give her child the power to decide what to learn, with adults to talk to, other children to play with and materials to explore with. Her search led her to the Sudbury model, where the democracy aspect stood out.

“Having a participatory democracy, where everybody has these long conversations, and you listen to all these different perspectives, in some ways, it feels tiring and inefficient,” she said. “But in other ways, I think it’s really efficient. Because eventually, everybody figures it out. So there’s more buy in.”

The school is open from from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. but students only have to be at Clearwater for 5½ hours, per state requirements. Students choose when they arrive and leave.

Klein did all his schooling at Clearwater.

He is invested in empowering students and loves how different his days at the school look. Some days, he’ll run around with 5-year-old. Others he’ll work on organizing workshops or talk about music with older students.

He said classes and initiatives can be organized, if students are interested.

There’s an occasional math class here and there, or a theater group every now and then. Recently, Klein organized a learning session about the crisis in Gaza. But Clearwater has never been a school with a lot of formal classes.

“The vast majority of the learning are the games that people play, the conversations that people have,” he said. “And just sort of existing in the world being part of a community and learning what you’re passionate about.”

‘Forcing everyone’

Through his years at Clearwater, Klein found his passion in theater. As a student, he cofounded a drama program. That’s when his days became more planned: Come to school, set up, rehearse, clean up. Not having homework allowed him to lean in and be in multiple shows at a time, both in and outside of school.

He also appreciated having the time to support his friends through their struggles with mental health.

He believes a one-size-fits-all model of a traditional school has unreliable results, when it’s “forcing everyone to try and learn stuff that they’re not interested in, and that they’ll forget really quickly,” he said.

The Clearwater School asserts its model works at all levels of education. But many parents wonder how well it develops fundamental skills like reading, writing and basic math.

“(Reading) happens pretty late compared to traditional education or societal expectations. In most cases, we tend to see people not having any interest in it,” Klein said. “When they have interest in reading, oftentimes there’s something they want to do that they can’t do without being able to read.”

He said some typical things that spur a desire for literacy in students include the video games they play or watching their friends reading.

The model isn’t foolproof, Klein conceded: Some dyslexic alumni felt the absence of education milestones prevented them from realizing their struggles and getting the resources they needed.

‘We lost our elders’

After the mandatory part of the weekly meeting, most students sprang out of the room, leaving behind a few students to continue on.

The next item on the agenda seemed appropriate: Should there be a “draft” that forces some students to stay through the entire meeting?

First, students debated the mechanics. Should it be a voluntary system, where only students signed up for the draft must attend? Or a random one?

Past attempts at conscription had backfired.

“It ended up getting a lot of very angry people that they had to be there,” one student said. “At some point, they started voting what would get them out of there quickest, instead of voting on what’s actually good.”

Cedar Gallien, the student who put that item on the agenda, retracted her idea, but the group agreed there should be more social pressure to attend the full meeting.

Sarantos explained later that since COVID-19, the student body has struggled to fully regain its school spirit. Older kids decided to graduate earlier during the pandemic.

“The 14- and 15-year-old students talk about how we lost our elders,” she said. “Everybody’s dealing with that same question of, ‘How do we get our connection with each other back?’”

Klein said since students enforce many rules, early graduations have led to a looser sense of collective responsibility.

Minutes later, the meeting abruptly ended. It no longer had the quorum of students required to cast votes. Clearwater rules require 10% of the school community be present for votes. Half of the attendees must be students.

‘Teaching myself how to find motivation’

Clara Bannon transferred to Clearwater in November 2020. She had good grades in public school, but struggled with anxiety.

In early 2021, Clara started shadowing an older student who led the meetings. When the other student graduated, Clara took the position. By doing so, she said, she has improved her communication skills, especially with younger students.

Younger students ask her questions, mistaking her for staff.

Despite her deep involvement, Clara’s focus was figuring out what interests her.

“I’m slowly teaching myself how to find motivation in myself, rather than from other people or systems,” she said.

“Sometimes I just want to be told what to do,” she added. “Sometimes, in an effort to maintain the spirit of the school, I can overwork myself doing something I’m not actually interested in doing.”

Willow Lambey, 14, has spent a decade at the school and has learned to code from older students.

This year, Willow has taken on chairing the Justice and Compassion committee.

Anyone can write up someone for a “JC” violation. Previous offenses include a stolen blueberry muffin, a messy kitchen and a broken toy. But the goal isn’t to find a culprit and exact punishment.

Willow remembered being scared of the judicial committee when they were younger.

“’Oh no, I’m in trouble. What am I going to do?’ I would hide under the table,” they recalled. “Then, I very much realized, ‘Oh, it’s not that scary.’ And all the people hosting it were students I knew and were not mad at me.”

The chairs ask the accused for their version of the story. Then, they turn to whoever reported the incident: “What do you want out of this case? What do you want to be different?”

Sometimes, Sarantos shifts the focus away from the specifics.

“Sometimes in a JC case, two kids are mad at each other,” she said.

She said she asks them: “‘Are you friends most of the time?’ ‘Oh, yeah, we play together most of the time.’ So you switch it over to: ‘Can they think about how to reconnect with each other on their own?’”

‘What is smart?’

Arlo Dolven, 24, attended school his entire life at Clearwater.

In 2017, Dolven enrolled in community college through Running Start. The first few days were nerve racking.

“I’d be thinking, ‘What if they asked me to do something that I can’t do? What if I have to go and write a bunch of really smart things on the whiteboard in front of everyone?’”

For his first English class, he wrote an essay comparing Clearwater and traditional education. He asked himself: “What is smart?”

In the essay, Dolven recounted how, at 14, a soccer teammate outside of Clearwater asked him to calculate six times eight. Dolven felt like a “complete idiot.”

Last spring, he graduated from Evergreen State College.

After getting his driver’s license and earning a 4.0 GPA in college, he felt “pretty smart.” He still didn’t know the multiplication tables.

Dolven, who now works for the Washington Conservation Corps, said Clearwater taught him to learn on his own.

“Clearwater gave me a lot of time to reflect on what I actually like doing and what kinds of things I find interesting,” he said.

The lack of structure prepared him to approach college with “a real sense of interest.”

Dolven is considering going to graduate school. Before that, he said, he is going to have to spend some time catching up on math.

Aina de Lapparent Alvarez: 425-339-3449; aina.alvarez@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @Ainadla.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.