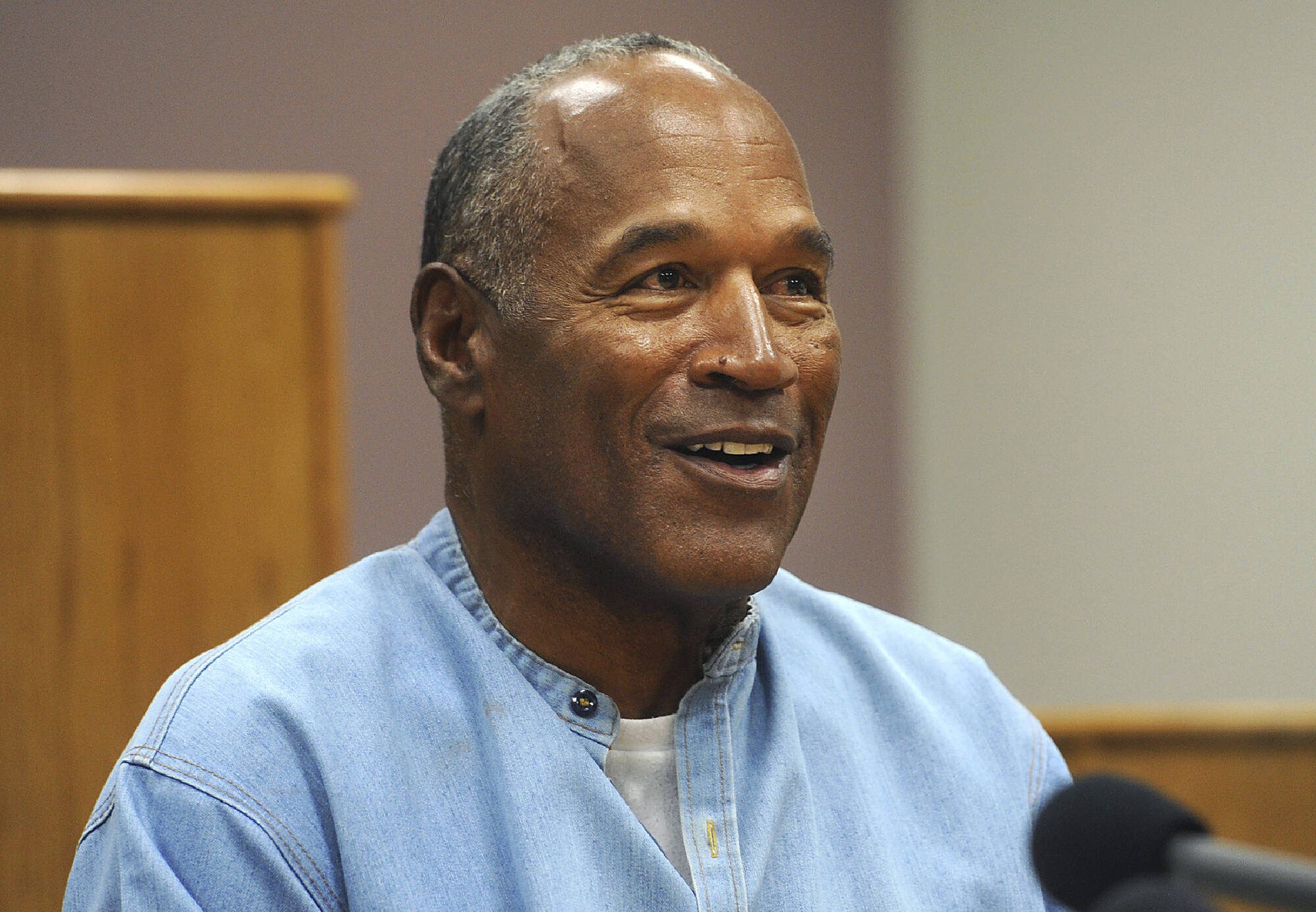

LAS VEGAS — O.J. Simpson, the football star and Hollywood actor acquitted of charges he killed his former wife and her friend in a trial that mesmerized the public and exposed divisions on race and policing in America, has died. He was 76.

The family announced on Simpson’s official X account that he died Wednesday of prostate cancer. He died in Las Vegas, officials there said Thursday.

Simpson earned fame, fortune and adulation through football and show business, but his legacy was forever changed by the June 1994 knife slayings of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ronald Goldman in Los Angeles. He was later found liable for the deaths in a separate civil case, and then served nine years in prison on unrelated charges.

Live TV coverage of his arrest after a famous slow-speed chase marked a stunning fall from grace.

He had seemed to transcend racial barriers as the star Trojans tailback for college football’s powerful University of Southern California in the late 1960s, as a rental car ad pitchman rushing through airports in the late 1970s, and as the husband of a blond and blue-eyed high school homecoming queen in the 1980s.

“I’m not Black, I’m O.J.,” he liked to tell friends.

His “trial of the century” captured America’s attention on live TV. The case sparked debates on race, gender, domestic abuse, celebrity justice and police misconduct.

Evidence found at the scene seemed overwhelmingly against Simpson. Blood drops, bloody footprints and a glove were there. Another glove, smeared with blood, was found at his home.

Simpson didn’t testify, but the prosecution asked him to try on the gloves in court. He struggled to squeeze them onto his hands and spoke his only three words of the trial: “They’re too small.”

His attorney Johnnie L. Cochran Jr. told the jurors, “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.”

The jury found him not guilty of murder in 1995, but a separate civil trial jury found him liable in 1997 for the deaths and ordered him to pay $33.5 million to family members of Brown and Goldman.

A decade later, still shadowed by the California wrongful death judgment, Simpson led five men he barely knew into a confrontation with two sports memorabilia dealers in a cramped Las Vegas hotel room. Two men with Simpson had guns. A jury convicted Simpson of armed robbery and other felonies.

Imprisoned at age 61, he served nine years in a remote northern Nevada prison, including a stint as a gym janitor. He was not contrite when he was released on parole in October 2017. The parole board heard him insist yet again that he was only trying to retrieve sports memorabilia and heirlooms stolen from him after his criminal trial in Los Angeles.

“I’ve basically spent a conflict-free life, you know,” said Simpson, whose parole ended in late 2021.

Public fascination with Simpson never faded. Many debated whether he had been punished in Las Vegas for his acquittal in Los Angeles. In 2016, he was the subject of both an FX miniseries and five-part ESPN documentary.

“I don’t think most of America believes I did it,” Simpson told The New York Times in 1995, a week after a jury determined he did not kill Brown and Goldman. “I’ve gotten thousands of letters and telegrams from people supporting me.”

Twelve years later, following an outpouring of public outrage, Rupert Murdoch canceled a planned book by the News Corp.-owned HarperCollins in which Simpson offered his hypothetical account of the killings. It was to be titled “If I Did It.”

Goldman’s family, still doggedly pursuing the multimillion-dollar wrongful death judgment, won control of the manuscript. They retitled the book “If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer.”

“It’s all blood money, and unfortunately I had to join the jackals,” Simpson told The Associated Press at the time. He collected $880,000 in advance money for the book, paid through a third party.

“It helped me get out of debt and secure my homestead,” he said.

Less than two months after losing the rights to the book, Simpson was arrested in Las Vegas.

David Cook, an attorney who has been seeking since 2008 to collect the civil judgment in the Goldman case, said he’d spoken with Ron’s father, Fred, on Thursday about Simpson’s death. Cook declined to say what Fred Goldman said or where he was.

“He died without penance,” Cook said of Simpson. “We don’t know what he has, where it is or who is in control. We will pick up where we are and keep going with it.”

Simpson played 11 NFL seasons, nine of them with the Buffalo Bills, where he became known as “The Juice” and ran behind an offensive line known as “The Electric Company.” He won four NFL rushing titles, rushed for 11,236 yards in his career, scored 76 touchdowns and played in five Pro Bowls. His best season was 1973, when he ran for 2,003 yards — the first running back to break the 2,000-yard rushing mark.

“I was part of the history of the game,” he said years later. “If I did nothing else in my life, I’d made my mark.”

Simpson’s rise in football happened simultaneously with a career in television. He signed a contract with ABC Sports the night he won the Heisman Trophy in 1968. That same year, he appeared on the NBC series “Dragnet” and “Ironside.” During his pro career, Simpson was a color commentator for a decade on ABC followed by a stint on NBC. In 1983, he joined ABC’s “Monday Night Football.”

Simpson quickly became a charismatic pitchman. In 1975, Hertz made him the first Black man hired for a corporate national ad campaign. The commercials, featuring Simpson running through airports toward the Hertz desk and young girls chanting “Go, O.J., go!” were ubiquitous for years.

Simpson made his big-screen debut in 1974 in “The Klansman,” an exploitation film in which he starred alongside Lee Marvin and Richard Burton. The film was a flop but Simpson would go on to appear in several dozen films and TV series, including 1974’s “The Towering Inferno,” 1976’s “The Cassandra Crossing,” 1977’s “Roots” and 1977’s “Capricorn One.”

Most notable, perhaps, was his performance in 1988’s “The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad” and its two sequels. Simpson played Detective Nordberg in the slapstick films opposite Leslie Nielsen.

Of course, Simpson went on to other fame.

One of the artifacts of his murder trial, the carefully tailored tan suit he wore when acquitted, was later donated and placed on display at the Newseum in Washington. Simpson had been told the suit would be in the hotel room in Las Vegas, but it turned out it wasn’t there.

Orenthal James Simpson was born July 9, 1947, in San Francisco, where he grew up in government-subsidized housing projects.

After graduating from high school, he enrolled at City College of San Francisco for a year and a half before transferring to the University of Southern California for the spring 1967 semester.

He married his first wife, Marguerite Whitley, on June 24, 1967, moving her to Los Angeles the next day so he could begin preparing for his first season with USC — which, in large part because of Simpson, won that year’s national championship.

On the day he accepted the Heisman Trophy, his first child, Arnelle, was born.

He had two sons, Jason and Aaren, with his first wife; one of those boys, Aaren, drowned as a toddler in a swimming pool accident in 1979, the same year he and Whitley divorced.

Simpson and Brown were married in 1985. They had two children, Justin and Sydney, and divorced in 1992. Two years later, Nicole Brown Simpson was found murdered.

“We don’t need to go back and relive the worst day of our lives,” he told the AP 25 years after the double slayings. “The subject of the moment is the subject I will never revisit again. My family and I have moved on to what we call the ‘no negative zone.’ We focus on the positives.”

Biographical material in this story was written by former AP Special Correspondent Linda Deutsch.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.