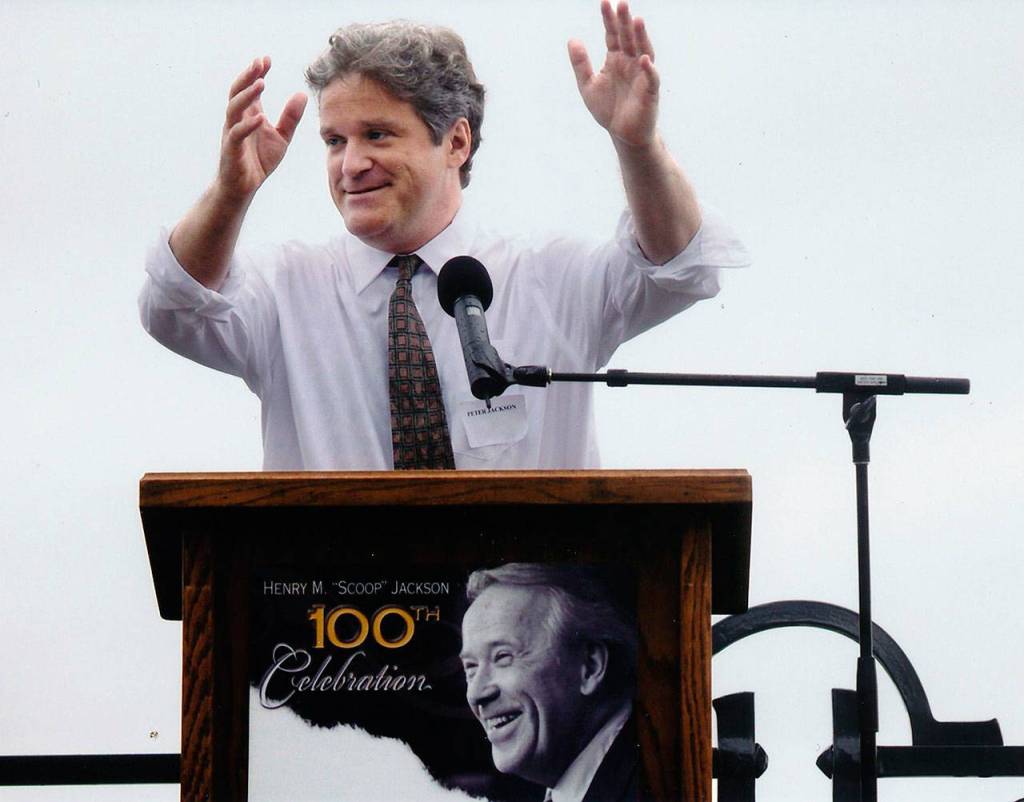

Peter Jackson, writer and Scoop’s son, dies of cancer at 53

Published 1:30 am Tuesday, March 24, 2020

Peter Hardin Jackson, son of the late U.S. Sen. Henry M. Jackson, was born into the world of political power, but that was not his path. A brilliant and eloquent writer, he used his commanding voice to champion the causes of human rights and the environment.

Jackson, 53, died Saturday evening in Seattle, where he lived with his wife of nearly 10 years, Laurie Werner. The Daily Herald’s editorial page editor from 2012 to 2014, in September 2016 he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. His determined fight to live included surgery, radiation and more than 65 rounds of chemotherapy.

“With the incredible support of Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, he just wanted to give it his all. He was full tilt,” Werner said Monday.

He was born April 3, 1966, in Washington, D.C., to Sen. “Scoop” Jackson and his wife, Helen Hardin Jackson. His father, who would later make a run for the White House, was a U.S. senator from 1953 until his death in 1983, and earlier served in the U.S. House.

Along with his wife, Peter Jackson is survived by his sister, Anna Marie Laurence and her husband Daniel Laurence, of Everett, as well as his nephew and niece, Jack and Julia Laurence.

“Peter was very humble, a bit soft-spoken, but he stood for the things he felt were important,” Laurence said of her younger brother. “My early memories, I think Peter was born with a book in his hand. He loved to read at a very early age. He challenged all of us with his writings and his incredible vocabulary.”

With the power of the pen, “his editorial pieces kind of opened our world,” she said.

She and her brother largely grew up in Washington, D.C., but spent summers and holidays in Sen. Jackson’s native Everett. Laurence now lives in the former Jackson home on Grand Avenue. Helen Jackson lived there until her death in 2018 at age 84.

Peter Jackson graduated in 1984 from St. Albans School in Washington, D.C. He attended the University of Washington as a college freshman, but graduated from Georgetown University in 1988 with a degree in government.

A VISTA volunteer in Port Townsend, he also spent time in the Los Angeles area and Washington, D.C., before returning to Seattle in the late 1990s. He worked as a speech writer for Gov. Gary Locke and later for Gov. Christine Gregoire before turning to journalism.

For Seattle-based Crosscut, an online news outlet founded in 2007, Jackson wrote the Daily Scan, along with articles covering politics in the region and nation.

While at The Daily Herald in 2014, Jackson won the Dolly Connelly Award for Excellence in Environmental Journalism for his pieces about coal and oil trains, the Hanford cleanup efforts, and a proposed pebble mine at Alaska’s Bristol Bay.

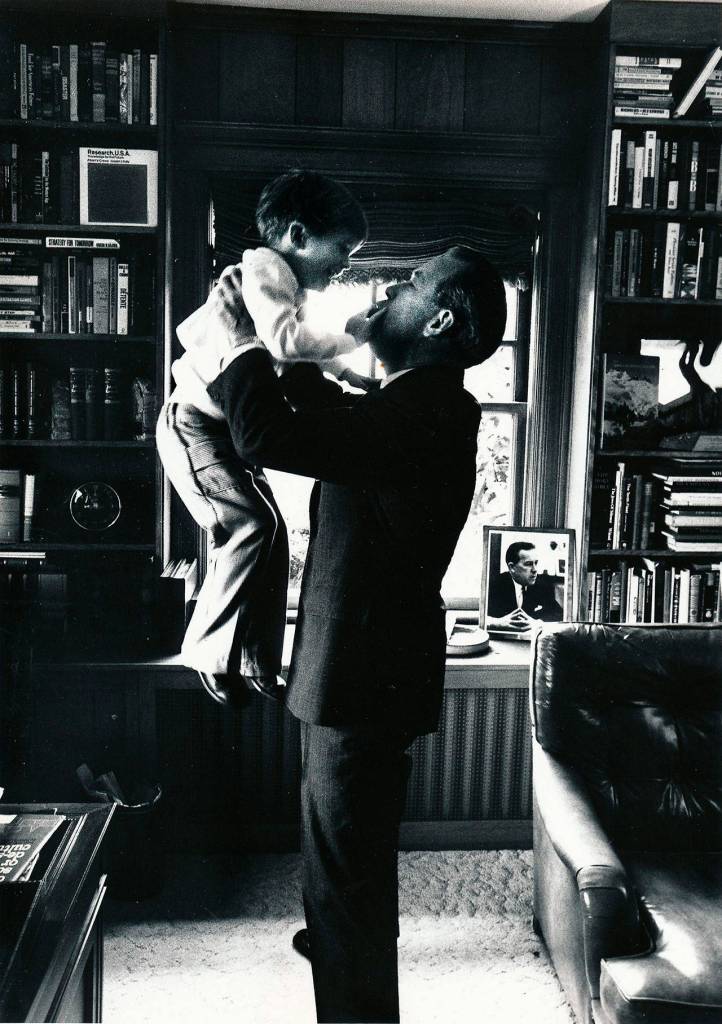

Bob Ferguson, Washington’s attorney general, met Jackson when they were UW undergraduates. On Monday, Ferguson recalled walking into Jackson’s room back then and seeing a picture of Robert Kennedy with a young child. Ferguson wondered which Kennedy child it was — but soon learned it was Peter Jackson as a boy.

That was a memorable start to their three-decade friendship.

Jackson was among those from whom Ferguson sought advice in his first campaign, for a King County Council seat. He’d bend Jackson’s ear often in the coming years because of the scribe’s knowledge of history, political aptitude and self-effacing demeanor.

“When Peter spoke, it was clear that that was the way to do it,” Ferguson said. “He never felt like he had to be the first one to speak. He would invariably be the most astute political mind in the room.”

On Facebook, state Rep. Mike Sells, D-Everett, said of Jackson: “A thoughtful, compassionate writer interested in human rights and conservation, he made anyone who met him feel like they had been friends for ages.”

“I looked forward to his intellect on display in his writings as the Herald editorial editor, in Crosscut and wherever he decided to park his ‘scribblings’ as he called them,” Sells wrote.

Nearly 130 comments on a “Peter H. Jackson’s Cancer Fight” Facebook page convey the respect and sadness of friends and colleagues.

“He was an amazing guy. Heartbroken,” wrote Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers.

“Humor and warmth belied deep, deep commitment to global human rights and to what is natural and unspoiled about the Pacific Northwest,” Joel Connelly, political columnist for the Seattle PI, commented.

“Absolutely heartbreaking — such a profound loss for his family, the UW, our entire community and world,” wrote Ana Marie Cauce, president of the University of Washington.

Angelina Snodgrass Godoy is director of the UW’s Center for Human Rights. In 2008, the Jackson Foundation endowed the Helen H. Jackson Chair in Human Rights at the university, which sparked enthusiasm for the Center for Human Rights there.

Godoy, who holds the Helen H. Jackson Chair in Human Rights, said Monday it was Jackson’s effort in taking to the Legislature the idea that resulted in the center’s founding. “I think of Peter as a lion,” Godoy said in a written tribute that likened Jackson to “a storybook lion … possessed of a great and generous heart.”

“Steadfastly loyal, relentlessly unassuming, Peter grew up in the corridors of power but he always seemed allergic to claiming status or recognition for himself,” Godoy wrote.

Like Ferguson, Paul Bannick met his longtime friend when they were students at the UW. “We were rebellious at times,” the Seattle man said. Bannick said Jackson helped him see the world differently, influencing him to turn from a computer software career to work in nonprofits and writing.

“He was a brilliant and gifted communicator,” Bannick said. “He was able to write in a way that really got at people’s humanity and shared values and yet was pointed and actionable, pushing people toward change and growth.

“He could wield a hammer and have it sound like a poem,” Bannick said.

His friend’s humor was unique. “Peter had this incredible wit,” Bannick said. “It never came at anyone’s expense.”

And like Godoy, Bannick said political power was never Jackson’s aim.

“He saw power in his life, and could have leveraged his name for that power. He eschewed that,” Bannick said. “He spent his life speaking up for the people and issues that had no power.”

Laurence remembers a childhood brush with power.

“At a very early age, Peter could recite all the presidents in 30 seconds,” she said. “Dad was so proud of him, he put Peter on the spot. He did that for President Nixon at the White House. And President Nixon said, ‘Don’t forget me.’ Peter was so smart and so well read.”

In Everett as a boy, he loved to spend hours in his backyard tree house, Laurence said.

Werner met her future husband at a fundraiser for John Kerry in 2004, the year the senator from Massachusetts ran for president. Later, she said, “I asked him out.” That first date was at Ivar’s on Lake Union.

They were married Oct. 31, 2010.

Her husband, she said, was so knowledgeable that after he died a friend noted, “I’m going to have to start using Google again.”

“He had so many books, and he read them all. I think that part goes back to childhood. He didn’t like being in the limelight,” Werner said.

Journalism was a true love. “He loved working in a newsroom — he so wanted to be back in a newsroom,” Werner said.

It was just March 15 that a commentary Jackson co-wrote with Craig Gannett, “Climate change poses national security threat too,” was published on The Herald’s opinion page.

When he wasn’t reading or writing, Werner said he loved documentary films, the jazz music of Miles Davis, and their two black cats, Jack and Leo.

Jackson loved poetry, too, and often posted favorites on Facebook. The last poem he shared was “In a Dark Time,” by Theodore Roethke.

Last week, Jackson and Werner established the Advancing Human Rights at Home Fund to support the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights. It’s being created, the paperwork says, to support work done by students and staff “to further the pursuit of justice and equality for all who live within our borders.”

To donate to the fund: giving.uw.edu/peterjackson

Herald writer Jerry Cornfield contributed to this story.

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.