PUD’s experimental solar power microgrid is ready to go live

Published 1:30 am Sunday, July 25, 2021

ARLINGTON — Solar power, batteries, cars that can charge buildings, a self-sustaining energy grid.

Snohomish County PUD’s $12 million microgrid is a clean energy experimenter’s dream. And it’s a tool that could one day become useful in the face of natural disasters, predicted to become more common as climate change persists.

It isn’t big, at least as far as electric projects go, but it’s big on ideas. The goal is to show all the possibilities of a microgrid, and give a chance for engineers to work out any kinks, while they still can.

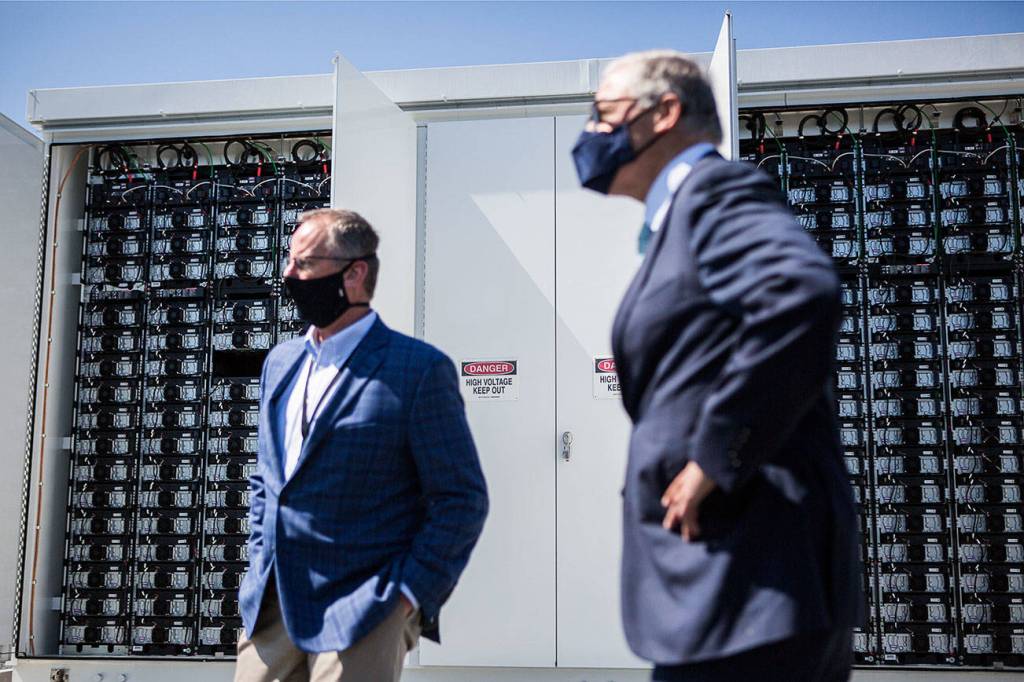

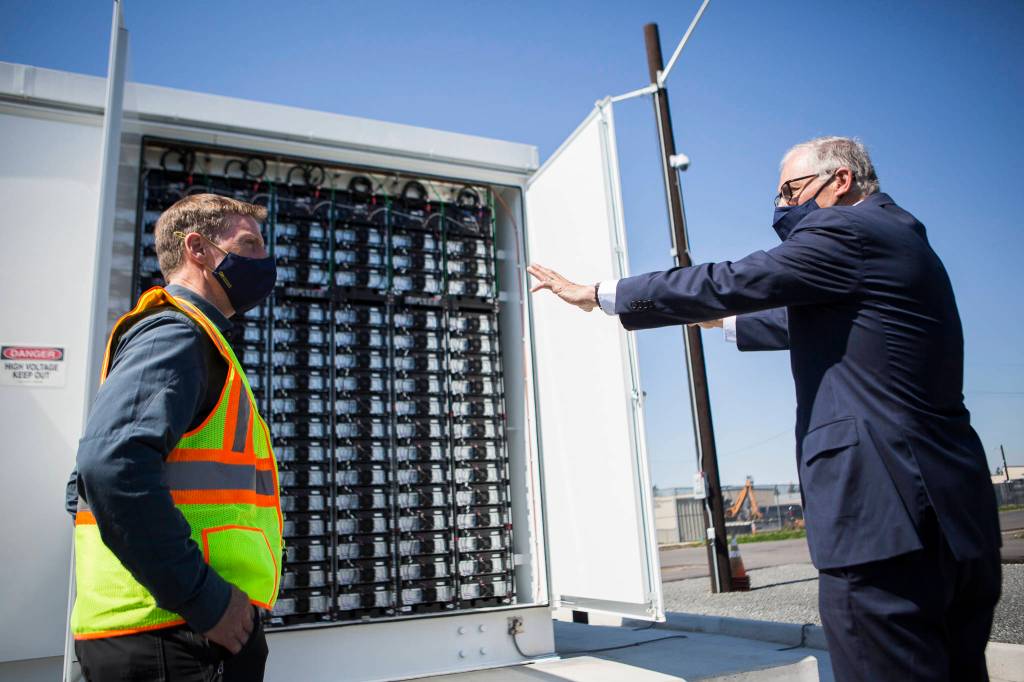

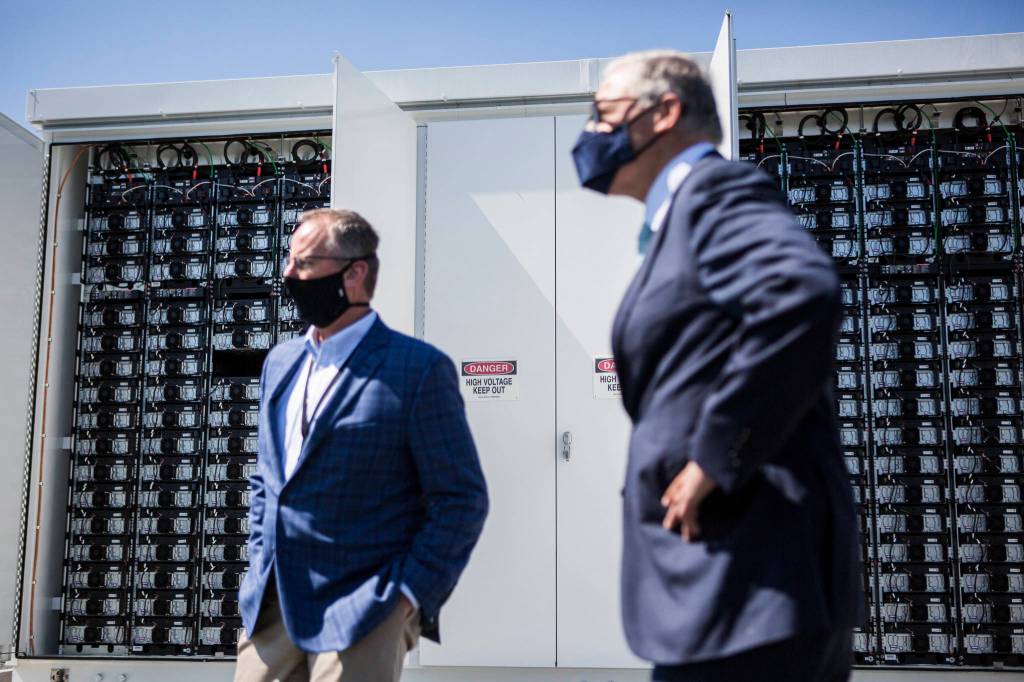

During a visit in April, the site near the Arlington Airport had Gov. Jay Inslee impressed. He marveled at the battery storage, and made sure to stand in front of the solar array for a photo opp. It was the type of innovation he wanted to see in Washington’s energy systems.

“I’m gonna brag about this,” Inslee assured PUD officials.

As of Friday, the microgrid is ready to be turned on, whenever needed. Project manager Scott Gibson said the team was doing some final tests and troubleshooting.

Gibson described the demonstration project as a “test lab,” a place where the PUD can learn how microgrids work and how to harness solar energy, an intermittent resource, and turn it into a reliable product via batteries.

“We’ve got to figure out how to make it work, and how to get value out of it,” Gibson said. “We know it’s part of our future. We’re not building more coal, we’re not building more gas. It’s going to be a long time before nuclear makes sense. Therefore we need to rely on wind and solar.”

So, what is a microgrid?

Simply put, it’s an electrical grid, but small.

Put another way, that loud gas-powered generator your dad drags out during an outage? You could call that a microgrid, of sorts.

Snohomish County PUD’s microgrid won’t be as loud or smelly, and it won’t produce any greenhouse gases, but it’ll still be an independent source of energy when the lights are out elsewhere. It uses solar power and stores any excess energy in batteries to save for a rainy day. The solar array takes up about three acres and can produce 500 kilowatts, which can then be stored in a lithium-ion battery system, with one megawatt hour capacity. With the system, they can generate enough energy to consistently power about 40 homes.

Then there’s the vehicle-to-grid system, built by Mitsubishi Electric Power Products in Japan. It’s a “very nascent” technology, Gibson said, that uses an electric car’s battery as an energy source. It’s not much — enough to power a home through the night — but it can make a difference at a critical moment. The PUD will study the impacts this use has on the car’s battery, and whether it makes sense to use electric fleet vehicles as grid support in the future.

There is a caveat to all this: There is a diesel generator on site, in case the solar and battery power runs out, and perhaps when there aren’t any more electric vehicles lying around. That’s a last resort, Gibson said.

In an emergency, the microgrid will power the PUD’s buildings in Arlington, which could become a vital base of operations as crews work to repair lines.

Compare that to the main grid the PUD operates, which powers more than 327,000 homes throughout Snohomish County and Camano Island, and another 33,000-some-odd businesses.

Having all those homes and businesses interconnected, while efficient, comes with its own problems. Power can be knocked out in large swaths, leaving hundreds or thousands of people in the dark and cold.

Meanwhile, a microgrid doesn’t have to be connected to any greater part. If power is cut off to other buildings on the same street, that’s not a problem.

The true value of a microgrid is on display during a natural disaster. Say a catastrophic earthquake hits, like one from the Whidbey Fault, where power would be knocked out for so many people when they might need it most. The PUD would send crews out to restore power, but that can take time — days or weeks, maybe months. The current go-to for backup power, diesel generators, require fuel, and that could be hard to get if roads are impassable.

Microgrids would become small sanctuaries of electricity that, in an ideal scenario, could become the backup for emergency services, like hospitals, fire departments and 911 call centers. They could also be used to power shelters, where displaced people could come charge their phones, see what’s going on, and experience all the comforts of having electricity.

These sanctuaries could become crucial, as the world sees more wildfires, hurricanes, winter storms and heatwaves.

The peculiar winter storm in Texas, for example, showcased how an ill-prepared electrical grid could be its own disaster. Millions were left without power or clean water in below-freezing temperatures. More than 200 people died as temperatures plummeted, some within their own homes.

When not in use as a backup generator, the PUD’s microgrid will supply solar power to the grid at large. That will help the grid pay for itself, as well as give a bit of a clean energy boost to the PUD’s portfolio.

Gibson calls it a microgrid with a day job.

“It’s actually earning its keep,” he said.

Today, if single sources of energy like a large dam or a giant coal plant were to suddenly become inoperable, the impacts would be severe. Imagine a world where there are a plethora of self-sustaining and clean power-producing microgrids where, if one went down, there would still be plenty of other sources to produce electricity. By spreading out our power sources, we can have a more reliable and more resilient electrical grid, Gibson said.

If these microgrids-with-a-day-job become more prevalent, he added, they could help reduce peak energy usage. When the utility district doesn’t have electricity to meet demand — usually only a problem during peak events, like cold winter days — then it has to buy energy from elsewhere. That can be more expensive, and could introduce fossil fuels to the mix.

In 2019, state lawmakers passed the Clean Energy Transformation Act, requiring utilities to remove fossil fuels from their portfolios. The law sets a goal for utilities to eliminate coal power by 2025, become carbon neutral by 2030, and completely carbon free by 2045.

Building the microgrid had its challenges, Gibson said. It’s expensive, first off, though a $3.5 million grant from the Washington Clean Energy Fund helped offset costs. The PUD also made a chunk of money upfront by letting people invest in the solar array, and it’ll make some money back from selling solar power on the grid.

A bigger challenge is that the PUD is used to building substations and powerlines, not innovative pieces of technology.

“This is complicated stuff, holy cow,” Gibson said.

The tech for solar power and batteries is also newer, and relies on a digital inverter to convert the energy the panels produce into energy we can use. That can be finicky, Gibson said. Fossil fuel plants, on the other hand, typically burn fuel to make steam, then use that steam to spin a turbine generator, and with it magnets and wire that create an electric current. It’s a reliable, tried and true method that’s been around for a long, long time. Those old turbine generators are typically more resistant to disruptions than the digital inverters, too.

It’s like buying a new car with all the electric bells and whistles. It takes some getting used to, and there are more things that can go wrong.

That’s not to say the microgrid won’t be reliable, just that experimenting with the technology has to start somewhere. Gibson said he’s thankful for the people with the project’s contractor, Hitachi ABB Power Grids, who have been willing to help troubleshoot at every turn.

“With every problem there’s a learning opportunity,” Gibson said. “We’ve had a lot of opportunities to learn.”

Those lessons will be incorporated in the building of future microgrids, either those built by the PUD, or with the PUD’s help. Gibson said he’s already received interest from businesses and agencies, like the Tulalip Tribes, that want to make their own.

“We’re quickly becoming the regional experts,” he said. “People are coming to us left and right.”

The next solar-powered microgrid the PUD builds, Gibson promises, will be better. And maybe eventually, they too will become the tried and true standards of electricity.

Zachariah Bryan: 425-339-3431; zbryan@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @zachariahtb.