EDMONDS — There are few blank walls in Brian Basset’s home, if any. It’s his personal art museum, covered with masks, paintings and framed cartoons. A cabinet near the kitchen is filled with miniature replicas of the Space Needle, and six display cases in the basement house his collection of sci-fi toy guns and model spaceships.

Basset, 65, has called the Meadowdale neighborhood in Edmonds home for the last eight years. In the yard, you’ll find him gardening on sunny days. But don’t bother asking him over for dinner or to spend a late afternoon by the fire pit, because the answer will always be a polite “No, thanks.” Evenings are for doodling, and Basset has deadlines to meet.

“I’m the only one in this neighborhood that’s not retired,” Basset said, “and nobody understands that I’ve got work to do.”

For more than two decades, Basset has sketched out the adventures of a boy and his dog in the newspaper comic strip “Red and Rover.” It runs in more than 300 papers including The Seattle Times, The Washington Post and The Daily Herald, of which Basset is a subscriber. The strip is distributed by Andrews McMeel Syndication, which also carries “Garfield,” “Peanuts” and “Calvin and Hobbes,” among others.

Basset believes he has another five years left in him as a comic artist before he brings “Red and Rover” to an end. In the meantime, he’s working to solidify his comic’s legacy while setting the stage for the next phase of his career.

‘Like you’re goofing off’

Basset spends up to 15 hours a day practicing his craft, sometimes forgetting to stop for meals.

Mondays and Tuesdays are set aside for brainstorming. The master cartoonist takes out his sketchbook, lets his mind wander and sees where the characters take him. It’s daydreaming with purpose.

“Even when a cartoonist is working hard, it looks like you’re goofing off,” Basset said. “And it used to drive my ex-wife crazy.”

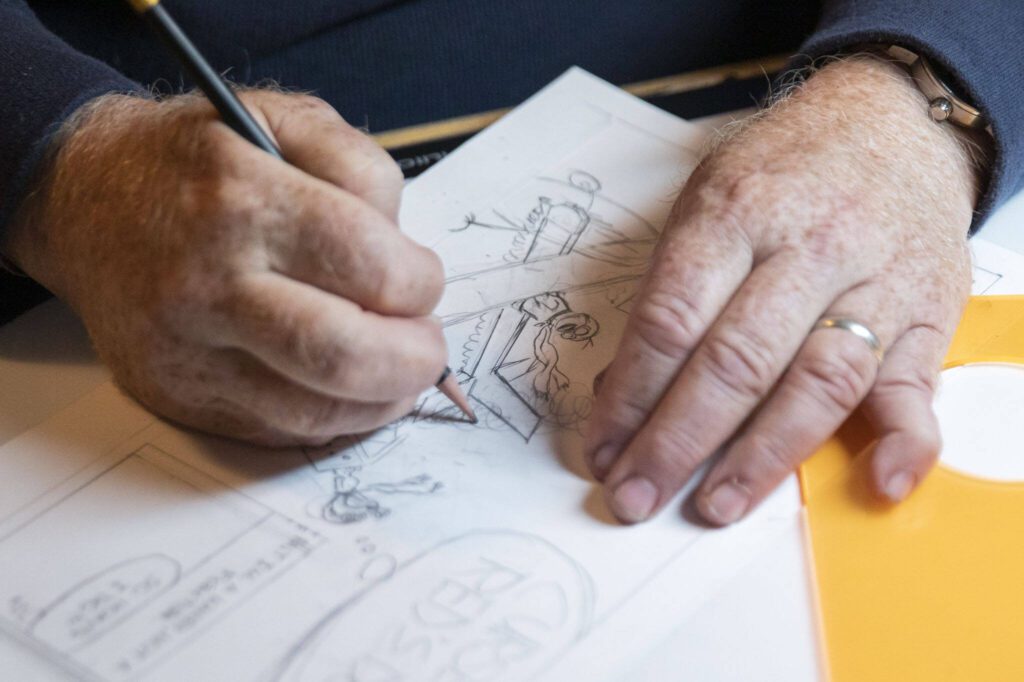

By mid-week, Basset is penciling at his desk in the basement. He is old-fashioned and forgoes the tablets and stylus that are standard today. He only uses a computer to scan and touch up his art in Adobe Photoshop. Basset loves the feel of paper and ending the day with ink-stained hands.

Basset works in silence, talking out problems in his head. With an array of pencils, pens, rulers and stencils at his fingertips, he regularly switches from drawing on his main sheet to sketching rough outlines of fresh ideas on loose scraps.

Little mistakes are covered by tape. Big errors lead Basset to tear the whole thing up and start again. Even though he has drawn these characters thousands of times, he can still encounter a challenge. He can’t work on autopilot. “Red and Rover” requires his full attention.

Each strip for Basset is a journey. By the time he’s done, a panel that should have taken an hour to finish stretches into six. Basset will redraw over and over until it’s just right.

“Whether the reader will recognize that or not, I don’t know,” Basset said. “But I will.”

‘Power of the image’

The son of a political cartoonist, Basset was made aware of what he calls “the power of the image” at an early age. His father Gene spent four decades working at a number of daily newspapers. Basset’s dad was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize and for a time served as president of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists, according to an obituary.

Basset’s father cultivated a love for the arts in his children. Brian Basset’s brother, Roger, studied at The Royal Academy of Arts in London while Brian was inspired to follow in his father’s footsteps.

“I just owe so much to him,” Basset said of his father. “He never pushed us or forced us into this, but we would just both marvel at the way he could take a sheet of paper and make it come to life.”

Basset was part of the generation of aspiring journalists galvanized by the Watergate scandal. He “wanted to be part of the good fight,” so in 1975 he enrolled in the journalism program at The Ohio State University.

Basset drew for his school newspaper and spent two summers interning at the Detroit Free Press. He was about a dozen credits shy of graduating before dropping out. A degree wasn’t necessary in the 20-year-old’s mind. He felt ready, and set out for Alaska. His dream was to work at the Anchorage Daily News.

“I was just too cocky for my own good, I will admit that,” Basset recalled. “I just wanted to go. I wanted to hit the road. I wanted to work in the real world.”

He traveled west and reached Washington in 1978. Basset said he fell in love with the landscape and decided to settle. A month later, The Seattle Times hired him. It was a six-month trial that would become a 16-year stint drawing editorial cartoons there.

Six years into the job, Basset was looking for fun and extra income. So he launched his first comic strip in 1984. It was one of the few avenues where he thought his career could expand.

“There’s an old saying,” Basset said: “A newspaper reporter can strive to become an editor, an editor can strive to become a publisher, and an editorial cartoonist can strive to be an older editorial cartoonist.”

The gag-a-day comic “Adam” follows the life of a stay-at-home dad. Basset quickly fell in love with making the strip, but it took time to get it right. He said his art was great, but his writing was terrible.

Writing didn’t matter so much when Basset was drawing political cartoons, as the imagery ultimately conveys the message. But for comics, crafting witty dialogue and characters with interesting personalities is key, and for Basset, “that was my biggest trip hazard right off the bat.”

Basset said about two-thirds of newspapers that ran “Adam” dropped it within the first year. It was a wake-up call, so he doubled down on his efforts to improve. He made his dialogue more crisp and he emphasized his characters’ body language. Learning those lessons eventually propelled him to his biggest hit.

A boy and his dog

Comics became Basset’s full-time profession after he was laid off by The Times in 1994. With a change in workspace, “Adam” was rechristened as “Adam@Home.” A few years on and Basset was itching for a do-over. He wanted to take everything he learned from trial and error and put it into a new strip, one that was good from the get-go.

The main character for the new comic would be Red, a 10-year-old boy largely based on Basset’s own childhood. Basset described Red as “a kid who’s happy, and that’s in short supply today.” The boy’s best friend is his dog Rover. The two are inseparable, and the strip would showcase their joyful friendship with the goal of putting a smile on readers’ faces.

“Dogs have always played such a huge part in my life, and I thought I’d tap into it,” Basset said. “When things were bad, I’d be off with my dogs talking to them about things. Having my dogs around meant everything.”

“Red and Rover” debuted on May 7, 2000, and was not the immediate hit it was created to be. It was slow to gain traction with newspapers. And eventually, drawing two weekly comic strips simultaneously took a toll on Basset’s health.

So, after about a decade, Basset decided to give “Red and Rover” his full attention. In 2009, he agreed to a contract buyout of “Adam@Home,” which was handed off to artist Rob Harrell.

“I took a big gamble,” Basset said. “I took a big paycheck cut. But had I not done that, I don’t think ‘Red and Rover’ would have become the strip that it is today.”

‘On my terms’

Basset is nearing the end of his comic career. While he loves cartooning, it takes a wear and tear on his body. He wants to retire at 70 and to give “Red and Rover” a fitting end, because the strip is “too personal” to hand off to someone else.

“I want ‘Red and Rover’ to retire when I go, on my terms,” Basset said, “because I don’t want it to have a different voice down the road by somebody else that’s not part of the makeup of the characters when I created them.”

Basset plans to donate his archive of original prints to the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum in Ohio. But the end of the comic will not mark the end of Basset’s career. He’s shifting his attention to writing, developing scripts for TV and film with screenwriters and other writing partners.

The last “Red and Rover” strip is not set in stone. Basset thinks it could end with an 18-year-old Red saying goodbye to an elder Rover before heading off to college, or an adult Red reminiscing over the life of his dog while at their favorite tree. Or maybe something more silly and lighthearted that wouldn’t be as upsetting to readers.

“They don’t want to believe that Rover could die, so I don’t want to necessarily provide them all that. It’s escapism,” Basset said. “I could change (my mind), but it’s going to be a very touching strip.”

Eric Schucht: 425-339-3477; eric.schucht@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @EricSchucht.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.