Related: Suicide-prevention resources and help for young people

MARYSVILLE — Steve and Sabrie Taylor made their Las Vegas getaway around Valentine’s Day last year.

It’s a special time of year for the couple, a celebration of their first date.

The trip marked the only time in their 18 years together that they would spend a couple of days away, just the two of them. They’d never left the kids alone before.

The night before their trip, they had a talk with their 19-year-old son, DeJohn “DJ” Ward. They told him he was responsible for looking after his sisters, Oshinaye “Osh” and Veronika Taylor, 15 and 12.

The next day, DJ drove his parents to the Bellingham airport. Sabrie told him she loved him.

DJ always had a big smile and a knack for being the center of attention. The 6-foot-4 former football player had accepted a new job that week. He and his girlfriend were counting the days until the birth of their boy, expected in the summer.

Steve and Sabrie hugged their son goodbye.

They were awakened by a phone call just before 2 a.m. Feb. 14. It was Osh.

DJ had hanged himself in the garage.

Suicides a wake-up call

DJ’s death was one of 12 in Snohomish County last year among 12- to 19-year-olds. It was part of a spike in youth suicides that saw the numbers more than double, from five the previous year.

Dr. Gary Goldbaum, health officer for the Snohomish Health District, said the dozen deaths should be a wake-up call to the community.

Snohomish County exceeds the statewide rate for suicides among 10- to 24-year-olds, with roughly 18 deaths per 100,000, while statewide it’s slightly more than 12 per 100,000.

When Wendy Burchill started working for the health district 15 years ago, there were at most three reported suicides per year. Some years there were none.

Last year, two 12-year-olds took their lives. “When you think of 12-year-olds in middle school, what does it take to get a kid there at such a young age?” Burchill said.

Clusters of suicides have occurred in Marysville, Stanwood and Mukilteo since 2014: four at Kamiak High School in Mukilteo, three at Stanwood High School and five in Marysville.

Students are taught about sex and drug use, but there isn’t much discussion of how they might feel when they lose someone and how to cope with that, said Angie Drake. The Stanwood mom said she couldn’t bear to see her teenage daughter come home one more time in tears because another student had taken their life.

She started a group, Survivors of Suicide Loss, in October 2015 after the deaths of the three Stanwood High teens within 10 months. She and other volunteers helped bring suicide prevention and intervention training to town.

“Someone’s got to talk about it, because the silence is killing people,” Drake said.

Yet for generations, suicide has been associated with a shame that was seldom discussed.

People tend to assume that suicide doesn’t happen in their community, not to their children or their children’s friends, Burchill said. Then it happens to three kids in one high school.

Hold on, pain ends

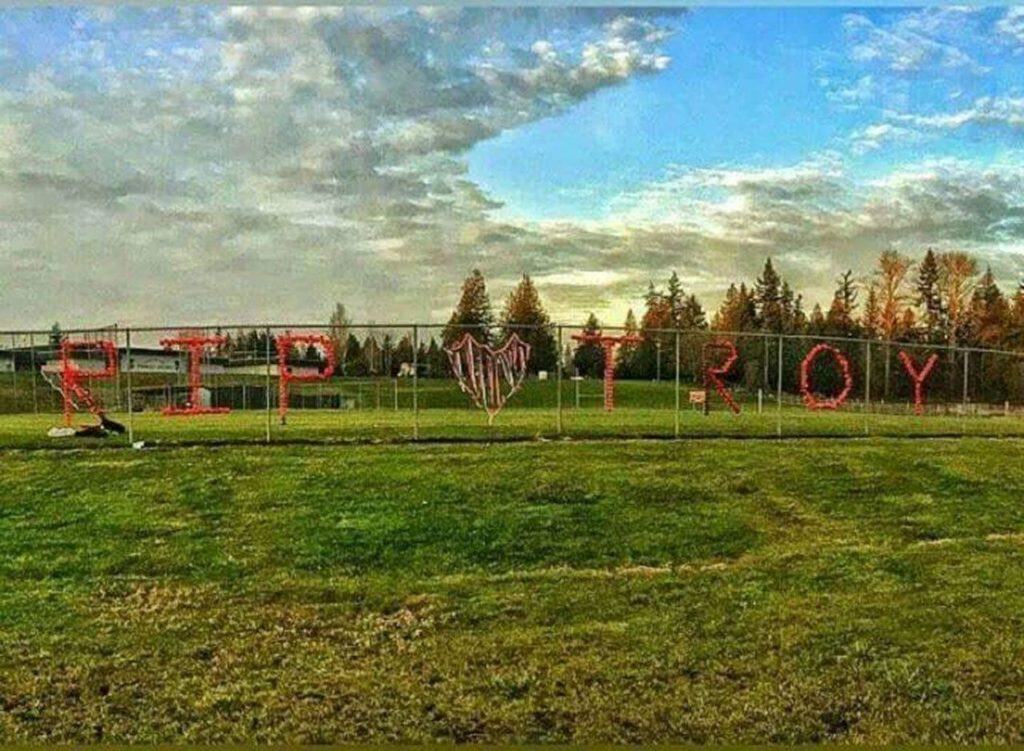

It was hard to miss the grief displayed on a grassy slope near Highway 532, the main road through Stanwood. Red cups had been pressed into the chain link fence surrounding the city’s only high school.

They formed the words “RIP Troy,” for a student who took his life in January 2015. Within 10 months, two more young men, ages 16 and 17, also would kill themselves, shaking the tight-knit community of 6,500 people into action.

Padlocks with names of the students scrawled on them dangled on the high school’s fence long after the cups were removed.

At the high school, administrators added district-wide staff training on suicide prevention. Legislation passed by the state in 2013 requires school nurses, social workers, school psychologists and counselors to be trained on youth suicide screening. The state requires suicide prevention education for middle and high school students. A statewide suicide prevention plan was released in January by the Department of Health.

Stanwood school administrators didn’t stop at the state requirements. They now have regular meetings with community groups, a volunteer program called Spirit Guard that brings more adults on campus, and an improved system for tracking and checking in with at-risk teens.

Suicide has been talked about briefly as part of the high school health curriculum for years, but the focus has shifted more toward prevention, and the unit expanded to multiple days, said Jennifer Zill, the school psychologist.

The district contracts with Catholic Community Services to have mental health counseling available twice a week. Parents can pay through insurance or, for low-income families, the cost is on a sliding scale.

Skyler Christofferson, 17 and a senior at Stanwood High School, went to middle school with one of the teens who killed himself last year. In the 1,200-student high school, the loss of a classmate hits hard. The loss of three was staggering.

Christofferson helped start an afterschool club called Team H.O.P.E. The name captures the message young people in Stanwood want to send to each other — Hold On, Pain Ends.

“We just want to make a place where people are comfortable being there for each other,” he said.

Last spring, club members put together flyers with Life Saver candies attached to them. The flyers reminded teens to ask each other questions, show they care and get help if needed.

There are a lot of things in place now that weren’t before, Zill said. It took the cluster of suicides to trigger such a strong community response.

“It’s not this dark secret,” she said. “We’ve brought it from the darkness into the light.”

“You are not alone”

Most people who have experienced some personal loss know that it helps to talk, said Rena Fitzgerald, who manages Volunteers of America’s online chat line, imhurting.org, where nearly half of the users are teens. Yet when someone says they’ve lost a loved one to suicide, people don’t want to talk.

“It scares them,” Fitzgerald said. “They don’t know how to deal with it, what to say.”

Youth coalitions have been started in Mukilteo, Monroe and Darrington to give young people a way to address the issues others may be scared to talk about, including suicide, depression and drug abuse.

The Mukilteo Youth Coalition handed out yellow wristbands to students as they returned to Kamiak High School for registration in August. The wristbands are imprinted with the number for the local confidential 24-hour crisis hotline.

Monroe’s youth coalition produced a video that was recognized by the health district for its strong message to other students: “You are not alone.”

The shift toward more public conversations about suicide isn’t just happening in schools. This summer, Sno-Isle Libraries hosted four open forums on suicide, including one in Stanwood.

An Out of the Darkness walk to raise money for suicide prevention and research is scheduled Oct. 15 at Everett’s American Legion Memorial Park. It’s the first time the event, part of a national campaign, has come to Snohomish County. The Everett fundraiser is one of at least 28 such walks planned around the country that day. It’s a time to be honest about emotions and share the weight of losses.

“The great lie we all tell is when someone says, ‘How are you doing?’ and we all say, ‘I’m fine,’” Burchill said.

Plans for the future

Some inner ticking clock still often awakens the Taylors. DJ is always on their minds, even in their sleep.

It’s always around 1 a.m, about the time Osh found her brother in the garage.

“For a long time I blamed myself,” Sabrie said. “I didn’t see the signs.”

She and Steve sometimes joke about whose turn it is to cry — she broke down yesterday, so he’ll break down today.

DJ could down a gallon of milk and a box of cereal in a day. Now, walking down a grocery store cereal aisle is a reminder for his mom.

She remembers DJ as a child, riding his bike down a flight of stairs. As a teen, he was the funny guy, the life of the party.

“As soon as he stepped into the room, everyone was like, ‘DJ’s here!’” Osh said. “Everyone wanted to be around him.”

She remembers her brother checking on his sisters to make sure they were serious about school and not goofing around. He wanted the best for them.

His dad still brags about his talent on the football field, where he played running back and inside linebacker. His trophies shine from a shelf in the front room of their home and his football jerseys hang in the closet of his parents’ bedroom. When he was a freshman, DJ suffered a concussion, barring him from play. Football was his thing, and without it he didn’t know what to do. That’s when he started spending his time with the wrong crowd, his parents said.

Run-ins with the law became more frequent. They included graffiti, burglary, marijuana use, and leading police on a chase through Marysville in his mom’s car. By age 16, he’d been referred to juvenile court multiple times.

DJ would be gone for days at a time. He’d call his mom to let her know he was OK, but worried his dad would be mad. On the phone with his mom, he’d tell her not to cry for him.

He pleaded guilty to burglary and illegally possessing a firearm in 2012. DJ spent time in juvenile detention and rehabilitation centers.

He “expressed his desire to make positive changes in his life,” a probation counselor wrote, but struggled to break free from drugs and peers that led him astray.

After a stint at Green Hill, a youth correctional facility in Chehalis, DJ earned his GED in 2014.

He began planning for the future. He wanted to go to college and train to become an underwater welder. It’s dangerous and physically demanding work, but with his athletic build and energy, DJ would have been well-suited to it.

In November, when the family was attending Osh’s soccer game at Arlington High School, DJ, smiling, told his dad the news he later proudly posted on Facebook. He and his girlfriend were having a baby.

He and his mom went on shopping trips, picking out infant outfits and baby essentials. His dad chuckled while DJ struggled to assemble a playpen, a moment captured in a family photo.

Two days before his parents left for their trip to Las Vegas, DJ was offered a job at a local plant nursery. The following day, he was offered a job at Walmart, which he accepted.

“We were having conversations every dad wants to have with his son,” said Steve Taylor, who took the father’s role in DJ’s life since he was 18 months old.

On his first day of work, while Sabrie and Steve were in Las Vegas, DJ texted his mom a photo. His Walmart shirt was tucked neatly into his pants.

The image of his father

The family moved within two weeks of DJ’s death. They couldn’t stay in that house. DJ’s friends helped pack up and haul away everything in a couple of hours.

They later learned DJ was on meth the day he died. His parents believe the drug pushed him over the edge. “Scared feelings of becoming a father, life is changing,” Sabrie Taylor said. “You take drugs and add to that mix. It’s an epidemic between drugs and suicide.”

Osh took a week off from school after losing her brother, then was back at it with classes and sports. The high school junior is taking college classes through Running Start. She and sister Veronika play varsity soccer and the family is at games most fall weekends.

DJ’s son, “Little DJ” as his family affectionately calls him, spends a lot of time at the Taylor house. He was born on June 12, four months after his dad’s death.

Family photographs hang on the walls of their new Marysville home. Among them is a picture of DJ when he was a toddler. Little DJ looks just like him — bright eyes, curly brown hair and the same smile.

He loves to dance. Strawberries are his favorite treat. He knows who his dad is and can point to him in the photographs.

This summer, the family gathered around their dining table while Little DJ crawled around on top of it. The framed photograph of DJ when he was a toddler sat on the table. Little DJ picked it up.

When Steve Taylor reached over to tug away the photo so he could give his grandson a hug, Little DJ pulled the image of his father closer and hugged it to his chest.

A few days earlier, while the family was watching TV, he pointed to a photo of DJ on the wall.

“Dad,” the little boy said, a grinning, giggling reminder of their son.

The Taylors dread the day when they’ll have to explain what happened to the missing person in the family photograph. That, Steve said, will be the hardest part.

Sharon Salyer: 425-339-3486; salyer@heraldnet.com. and Kari Bray: 425-339-3439; kbray@heraldnet.com.

Related: Suicide resources and help for young people

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.