EVERETT — Snohomish County is mostly on track to step into “phase two” of its opioid settlement spending plan, starring a mobile treatment program for homeless, low-income and rural residents.

So far, the county has spent about $2.3 million of the more than $8 million it has received from opioid lawsuit settlements. It’s a fraction of the $35 million the county expects to get over the next 16 years, Emergency Management Director Lucia Schmit said in an update to County Council members Tuesday.

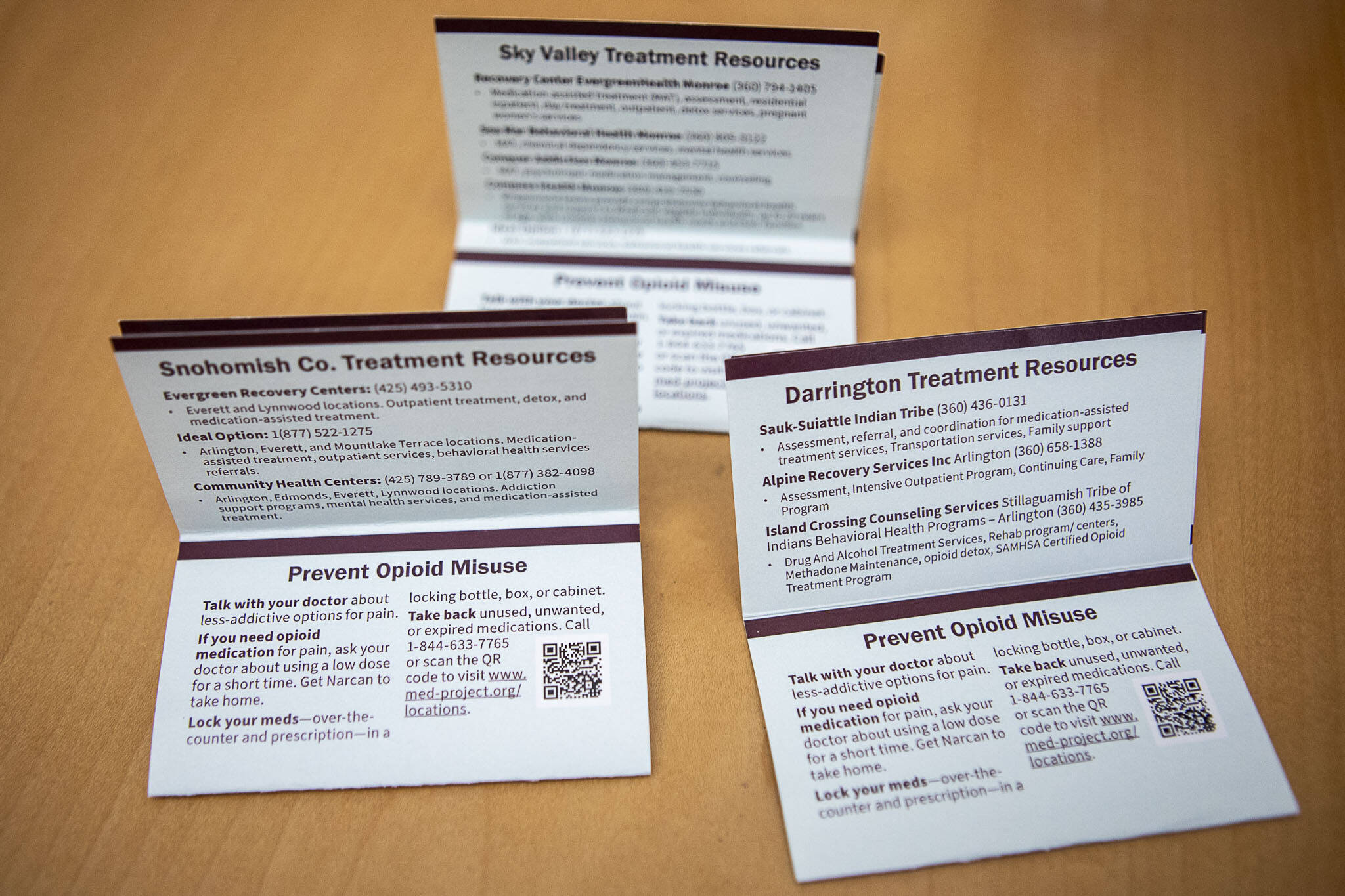

Phase one of the two-phase spending plan included staffing up county overdose prevention programs, distributing the opioid-reversing medication naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan, and distributing some money to local recovery-focused nonprofits.

This fall, the county plans to launch a mobile opioid treatment program. The county spent about $500,000 to retrofit a van to travel parts of Highway 2 and Highway 530, where Acadia Healthcare workers will provide opioid addiction medication and other recovery services. But the annual cost to keep up the program — about $900,000 — is “significantly higher” than expected, Schmit said. Initially, the program was budgeted for $600,000 per year, and the entirety of phase two was supposed to cost $800,000.

The initial spending plan was conservative, Schmit said, with sustainability in mind. Right now, the county has enough to run its current opioid settlement programs for four years, at a cost of about $1.9 million per year.

Council member Sam Low said he was looking forward to the mobile program’s launch since rural residents lack access to drug recovery services. Schmit agreed it was “money well spent.”

The county is also dispersing a second round of grants to local drug recovery organizations. Applications are due Sept. 8. The grants will be about $7,500 each.

Snohomish County’s opioid-related deaths hit an all-time high last year, at 269 reported deaths. In 95% of cases, the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl was involved.

This year, the county has reported 155 opioid-related deaths as of July — a 28% decrease compared to the same time last year. Overdose deaths are declining nationwide, and have plummeted in the county since February. Health Officer James Lewis has said the county’s prevention and treatment efforts are likely part of what’s working.

By October, Washington had won more than $1.1 billion from multiple lawsuits against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors for their roles in the opioid crisis. The state awarded half to local governments, including $28.9 million to Snohomish County.

After more recent settlements from Johnson & Johnson and Kroger, the county expects more than $35 million. The total comes from a hodgepodge of settlements with varying amounts, and payment schedules ranging from one to 16 years.

In April 2023, the county approved a plan to spend the initial settlement money on two phases of direct opioid response efforts, with local taxes, state and federal grants filling in the gaps.

The county reached most of its phase one goals. It hired an emergency management program manager for $135,000 per year. In April, it began distributing $77,800 to 11 local recovery agencies. Shortly after, it hired an epidemiologist for $125,000 a year to join its substance use prevention team. It enrolled in the nationwide “Leave Behind” program, where first responders have provided at-risk residents with more than 70 Narcan kits. It also partnered with the state’s recovery hotline, using caller data to better determine residents needs.

The county has adjusted some parts of its plan. Originally, $130,000 was supposed to be allocated for the Snohomish County Agencies for Engagement, or SAFE, a team of doctors, paramedics, social workers and police targeting homelessness. It turns out the team is ineligible for settlement money, so the county is looking to a new public safety sales tax it hopes voters will approve in November’s general election to fund SAFE.

The county also held off on hiring a primary prevention educator, at $200,000 per year, who would have taught opioid addiction prevention in public schools. This past legislative session, the state tasked the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction with developing updated drug curriculum. The county is waiting to see if additional education efforts are needed.

As a result, county officials re-allocated some money in the budget toward more grants for local drug recovery organizations.

The county will evaluate and change its spending based on program performance, Schmit said, and will continue seeking outside funding, including state and federal grants.

“Thirty-five million dollars is not nearly enough,” she said, “to fix the scope of this problem in our community.”

Sydney Jackson: 425-339-3430; sydney.jackson@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @_sydneyajackson.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.