SNOHOMISH — Two signs at Willis D. Tucker Community Park troubled some residents on the morning of Aug. 14.

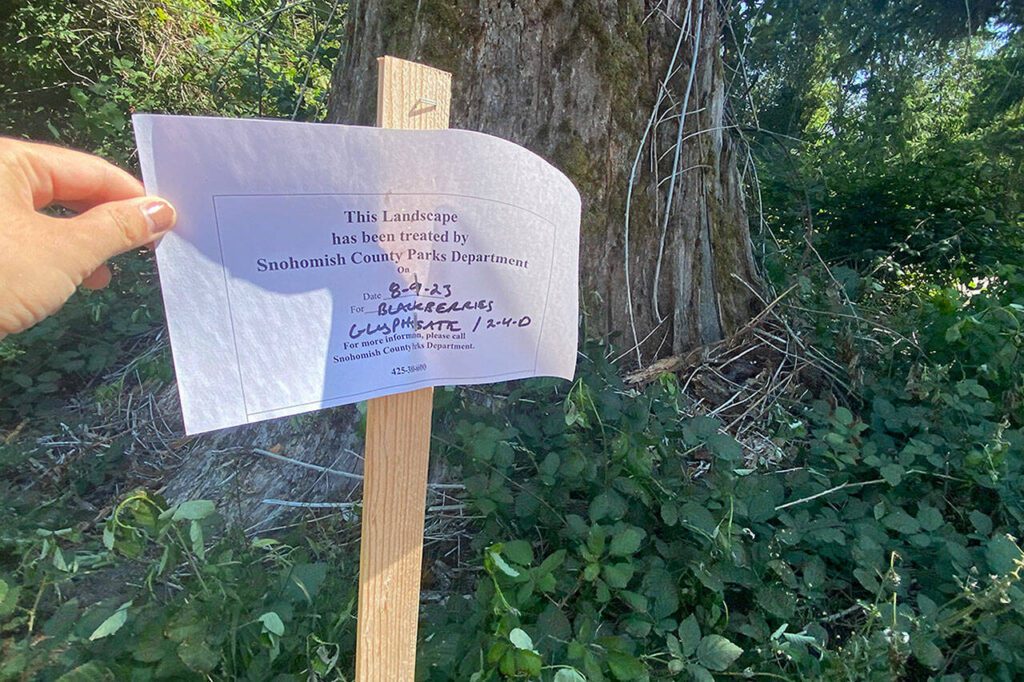

Staked just beyond the outer edge of the park’s baseball fields, the signs said blackberry plants nearby had been treated with the herbicides glyphosate and 2,4-D several days earlier.

When resident Norm Hagen saw the signs, he got upset. County staff told him they didn’t spray at the park, he said.

“I’m just really concerned and I’m pissed,” Hagen said. “We use that park three to four times a week.”

Historically, there has been conflicting information about the safety of herbicides like glyphosate, also known by the brand name Roundup. County officials familiar with the products said they are safe when users correctly follow the labels. Still, the Snohomish County Parks and Recreation Department said staff try to use other methods of removal before spraying plants in public spaces.

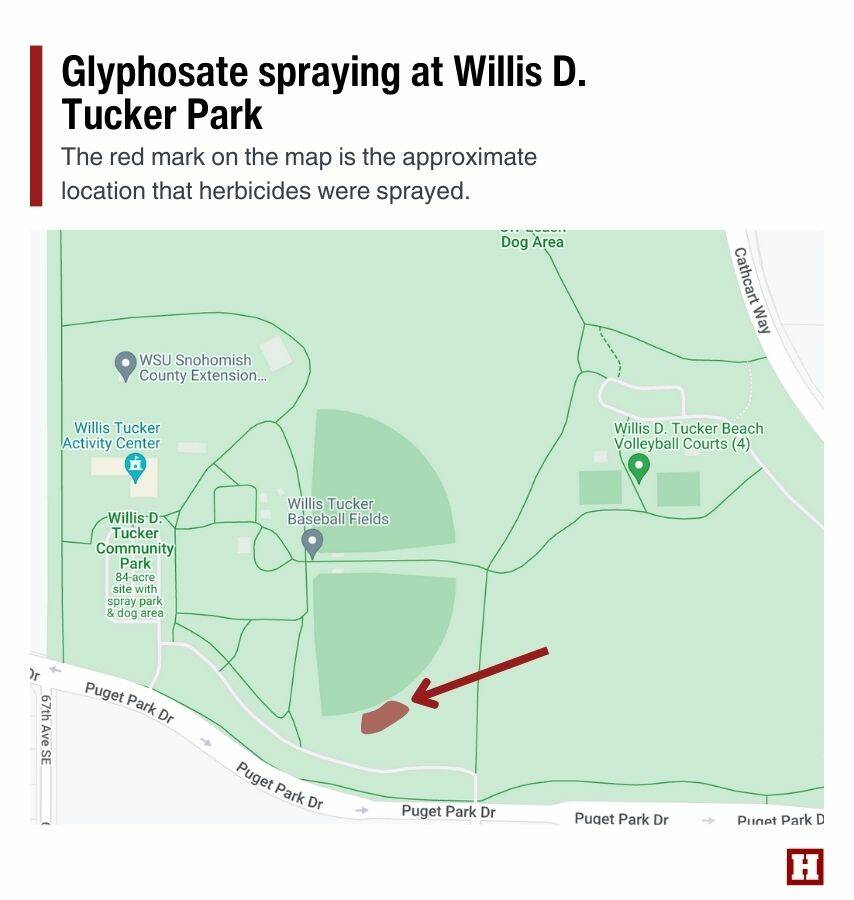

The area in contention at Willis Tucker Park east of Mill Creek is 11,000 square feet in the park’s southeastern region, away from any trails. Park staff planted about 100 native plants there in February, including Douglas fir, cedar and ferns, as a part of a county effort to create more habitat for native species.

Before the planting started, staff removed Himalayan blackberry, poison hemlock and Scotch broom plants by hand. The state Noxious Weed Control Board considers all three “noxious weeds,” a legal term for invasive plants that are aggressive and difficult to control. Poison hemlock is also toxic to humans and animals if ingested, so park staff remove the plant — which is in the carrot family — to ensure park users don’t pick it.

The invasive plants at Willis Tucker Park continued to reemerge, so licensed and trained applicators sprayed the plants with glyphosate and 2,4-D on three different occasions, park staff said. In May, the invasive plants were treated with 11.25 ounces of herbicide, then 11.25 ounces again in July and 1.45 ounces in August, according to the county’s application records.

When invasive plants aren’t controlled in these areas, there’s a risk the native plants won’t thrive, said Sharon Swan, division director for county parks.

“For the most part, we do really try and use mechanical means of controlling the competitive species,” Swan said. “That might be mowing, or it might be hand-pulling or weed-whacking. But in some cases, those don’t really work well.”

That’s when the county applies herbicides, Swan said.

The blackberry plants were small when the herbicides were applied, Swan said, and there weren’t any blackberries growing on them.

“We don’t apply to fruit,” she said. “We do know people are out in the parks, and that’s appealing, so we wouldn’t do that kind of application.”

‘Safe spaces’

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer concluded glyphosate is “probably carcinogenic to humans.” The agency noted the conclusion was based on “limited evidence” people exposed to glyphosate had higher rates of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The Sierra Club’s policy on glyphosate also references the International Agency for Research on Cancer study and warns glyphosate could “contaminate and harm all facets of an ecosystem, including the soil biology and composition, water and non-target plants, … animals and humans.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency assessed glyphosate’s safety again in 2020, however, and found “there are no risks of concern to human health when glyphosate is used in accordance with its current label.”

Federally approved glyphosate products have “caution” labels, said Geraldine Saw, the county noxious weed control board coordinator. Caution labels describe chemicals that are “the least toxic,” compared to products with “warning” or “danger” labels, Saw said.

“The toxicity is just so damn low,” said Allan Felsot, a specialist on pesticides who teaches at Washington State University’s campus in Tri-Cities.

Felsot reads articles and peer-reviewed scientific research on glyphosate almost daily, he said. As a pesticide specialist, he addresses controversial issues associated with pesticides. He said there isn’t enough education about pesticide use and the decisions that go into approving them.

When toxicologists — especially in academia — conduct research, they want to get results, Felsot said. So scientists inject high levels of chemicals into animal test subjects.

“And boy, do you get results,” Felsot said. “But that’s not the same thing as when you go out and spray it.”

The herbicide 2,4-D also has low toxicity to humans, meaning people would have to be exposed to over 500 milligrams of the chemical to be poisoned. Felsot said park agencies generally seem to avoid using it because of the smell.

“You can walk through a neighborhood and you know when people have been spraying 2,4-D products,” he said.

In recent years, Swan said park staff typically only sprayed when they were doing restoration projects.

Park staff have used herbicides on three occasions so far this year — all at Willis Tucker Park.

“We have over 100 individual properties that we manage and thousands of acres,” Swan said, “and out of all of that, there were only three applications because we are mindful of … the other mechanisms that we can use to get to the end that we need.”

Swan said the county follows an integrated pest management plan to evaluate the presence of an invasive plant and methods for controlling it.

“We want parks to be safe spaces,” Swan said. “That’s why we’re very careful about following all the rules and really choosing the best tool.”

Ta’Leah Van Sistine: 425-339-3460; taleah.vansistine@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @TaLeahRoseV.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.