EVERETT — A newly-hired lawyer came into Kathleen Kyle’s office at the Snohomish County Public Defender Association baffled by a system that seems to fail some of the community’s most ill.

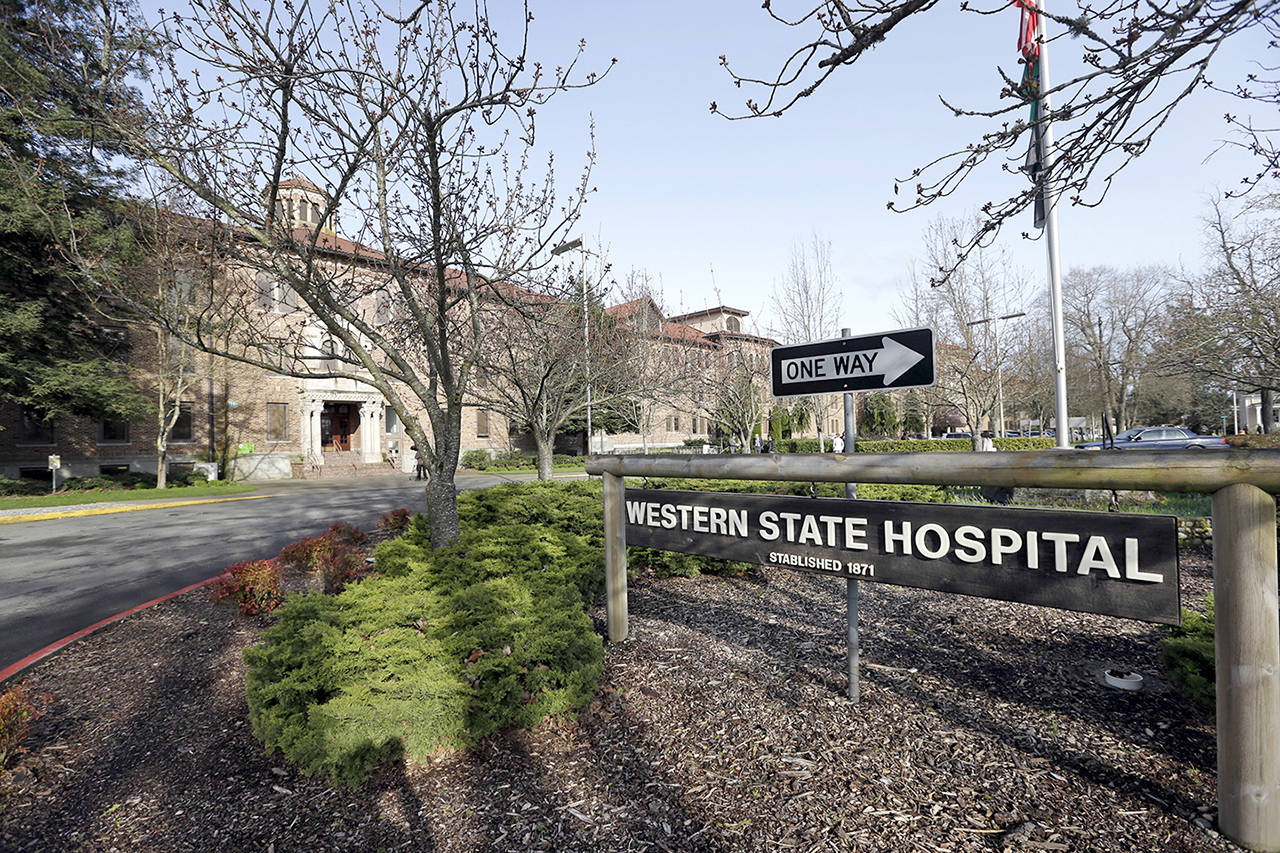

It was another case of a mentally ill client waiting for admission to the problem-plagued Western State Hospital. The client, charged with a misdemeanor, was too sick to help his defense attorney and a judge had ordered him to be treated at the state psychiatric hospital. The client was in the county jail waiting for a hospital bed.

The lawyer doubted that the man would be competent to stand trial and the case likely would be dismissed, although prosecutors weren’t budging. Meanwhile, the attorney was worried about her client’s deteriorating health.

She asked the boss what else could be done.

Kyle, the executive director of the association, had heard it all before.

Lawyers in her office were the first to sue the state Department of Social and Health Services for the long wait times at the state’s psychiatric hospital. The federal lawsuit was taken over by nonprofits, including Disability Rights Washington, and a federal judge sided with them, saying the state was violating the constitutional rights of inmates who were waiting weeks — sometimes months — for treatment.

A federal judge ordered the state to fix the problem and assigned a monitor to track its compliance. By last week, the state had racked up about $15 million in contempt fines for failing to provide timely admissions to inmates needing competency restoration treatment, said Emily Cooper, an attorney with Disability Rights Washington.

That amount is more than what the plaintiffs ever expected, she said. The fines are based on how long it takes the hospital to admit each patient waiting for restoration services. In recent months, the state has averaged more than $2 million a month in contempt fines, Cooper said.

“The state is going backwards,” she said. “The state is not taking to heart its obligations to serve and treat patients.”

U.S. District Court Judge Marsha Pechman ordered those fines to be spent on diversion programs. In March, she agreed to distribute $4.2 million among five different agencies, primarily mental health organizations.

The fines were doled out to develop programs to provide more timely treatment, ease the burden on jails and relieve some of the pressures at the state’s psychiatric hospitals.

A chunk of that money is headed to Snohomish County for an 18-month pilot program. The competency diversion program will be aimed at inmates who are too sick to assist with their own defense and need intensive mental health treatment.

Sunrise Community Behavioral Health applied for the nearly $1 million grant late last year with encouragement and help from Kyle and Hil Kaman, the city of Everett’s public health and safety director. The program will be carried out with the cooperation of the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office, which is responsible for the jail, allowing Sunrise mental health professionals access to inmates while they are incarcerated.

The Snohomish County Prosecutor’s Office also agreed to join the efforts and will add a counselor to monitor participants in its Therapeutic Alternatives Program. The office will be the gatekeeper, deciding which cases will be diverted.

The program will not accept people accused of a sex offense or serious violent crime, Snohomish County Prosecuting Attorney Mark Roe said.

“I think the public expects us to be careful about who we offer this to and allow in,” he said.

The program also was designed to include municipal court cases that otherwise would be handled by a city prosecutor.

That’s good news for Everett, Kaman said. The city has one of the highest numbers of Snohomish County jail inmates waiting for beds at Western State Hospital, second only to the county. Cities pay a daily fee to house inmates jailed on misdemeanor cases. They can be charged more to house a person with a mental illness.

The goal of the diversion program will be to move mentally ill inmates out of jail and connect them with behavioral health services and other resources, such as housing and public insurance. They will have frequent contact with a mental health professional and also will be required to have regular meetings with the counselor in the prosecutor’s office. If all goes well, the criminal charge can be dismissed.

“The idea is to create a safety net,” Kyle said.

That could keep some from rotating back into the criminal justice system. In many of these cases, charges are dismissed because the defendants are too sick to help with their own defense and competency cannot be restored. Often they are released back into the community without any intervention by social services.

If they are waiting for a bed at Western, they frequently are held well beyond any sentence they would receive for a misdemeanor conviction, such as shoplifting. Their conditions often get worse behind bars because a jail isn’t meant to treat the severely mentally ill, Kyle said.

“The program is designed to get them out of jail sooner and get them help sooner,” she said.

Sunrise has a good reputation in the city, Kaman said. The organization has been involved in Everett’s efforts to intervene in the lives of mentally ill people who often are involved in the criminal justice system and are frequent users of emergency medical services and crisis care. Kaman said Sunrise staff is willing to try creative approaches to assist their clients.

Some of the challenges can be building relationships with folks who turn down services. Some, because of their mental illness, don’t think they need help. Sunrise works with these clients, building trust over time, Kaman said.

As part of the grant, Sunrise and the other recipients must track their outcomes. If they are showing good results, the grants could be expanded or the programs could be replicated in other communities, Cooper said.

This could be the something else that the Snohomish County defense attorney was hoping to find when she walked into her boss’s office.

Diana Hefley: 425-339-3463; hefley@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.