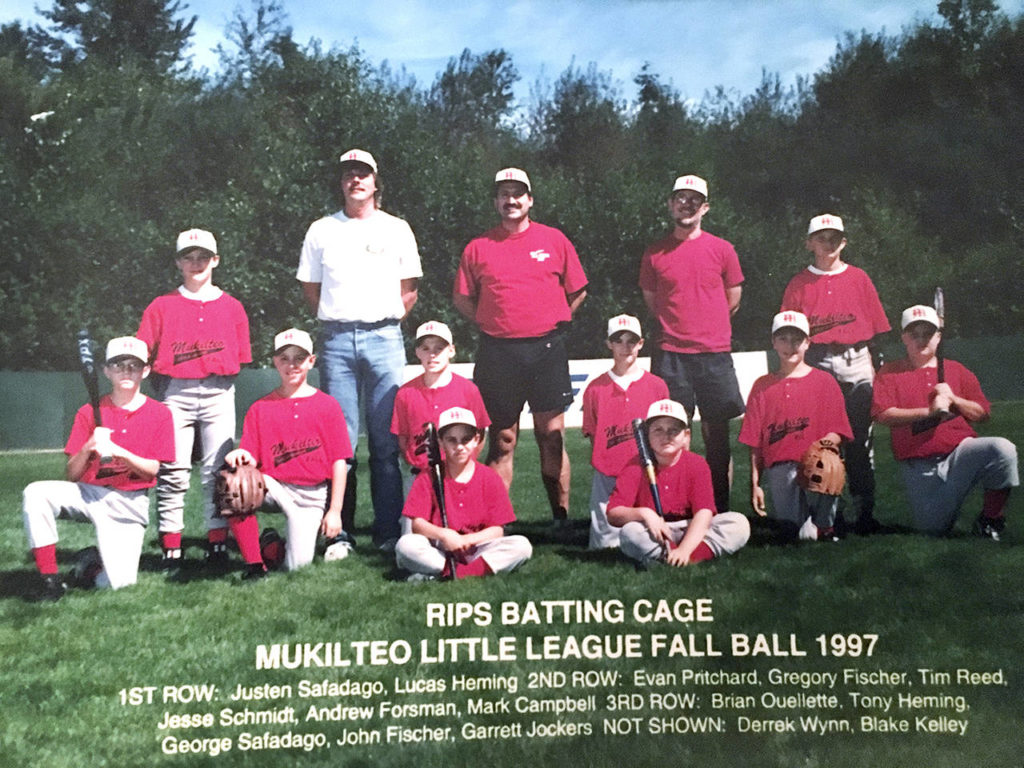

MUKILTEO — Ten kids lined up in rows on the outfield grass and squinted into a camera on a sunny day, for a Little League photo that Brian Ouellette has held onto since fall 1997.

Standing in the third row was Ouellette, 11, with his hands behind his back, his red Mukilteo baseball shirt tucked in and his face shaded by the bill of a white ball cap.

He was a standout pitcher who lived across from the fire station in Mukilteo’s Old Town. Two spots to his left, coach George Safadago smiled under a thick black moustache. He recalled Ouellette, even at a young age, had a special arm. Later, as a college prospect at Gonzaga University, a radar gun told the right-hander he could touch 93 mph with his fastball.

Ouellette didn’t recognize his old coach on the evening of March 7, when Safadago collapsed along the Mukilteo Speedway. Safadago didn’t recognize the former ballplayer from 21 years ago, either. He’d landed face-first on the sidewalk, and felt nothing. His memory went blank the moment he passed the post office, 40 yards from the spot his heart stopped. Usually a heart attack gives warning. The cardiac arrest suffered by Safadago, 60, did not.

“I was dead before I fell,” Safadago said.

Ouellette led a team of firefighters from Mukilteo, Everett and south Snohomish County who performed CPR. After about a half-hour, Safadago’s heart found a rhythm again.

A walk

Safadago weighed 308 pounds when he began a new diet and exercise plan in October. No pasta, no rice, no potatoes. Instead of bread on his sandwiches, he’d swapped in romaine lettuce. It wasn’t as good, he admitted, but it was working. The day before his cardiac arrest, the scale read 231. He’d shed 77 pounds.

Along with cutting carbs, he’d been walking two miles a day — a mile uphill, a mile downhill — starting from his home on the speedway. He’d picked a bad time of year in Washington to commit to daily exercise. Anytime he stepped outside, he said, it seemed to start raining. On a whim that Wednesday, he made up his mind to double his distance. Maybe it was too much, too soon. But part of Safadago wonders what could have happened if he’d fallen somewhere less visible, like at home.

George and Trudy Safadago have lived in their house since the 1980s, when the speedway was two lanes, the fire department was volunteer and downtown Mukilteo was pretty much all of Mukilteo. These days George commutes to King County for his transit maintenance job. Trudy is a records specialist for the state Department of Corrections office in Everett.

Her work day was ending when George texted her he’d reached his turnaround point, as he did on every walk. She scolded George that he’d gone too far.

“We’d talked about you increasing,” Trudy said to him later. “But we didn’t talk about going all the way to Walgreens.”

She texted about dinner. He didn’t answer, and suddenly she felt like something was off, she said. She drove toward home, and about a half-mile from the house saw an ambulance stopping ahead of her around 5:10 p.m., near the Lodge Sports Grille. She drove by slowly. Beneath the huddled crowd, she caught a glimpse of a red coat, the color of the Spyder jacket that was her husband’s favorite.

She called one of their sons.

“Is Dad at home?” She was hysterical, she said. “Tell me Dad’s at home. Go through the house, and tell me he’s at home.”

She turned around and got out of the car. Police held her back. In retrospect, she said, the officers probably feared she would have a heart attack and need an ambulance, too.

A hold

The 911 call reported a man down across from a bus stop. He had no pulse. He wasn’t breathing. The bridge of his glasses left a gash in his nose. Blood covered his face and forehead. No one had started CPR.

An aid crew on Medic 24 arrived in minutes. Ouellette, Capt. Ed Krikawa and probationary firefighter Darrell Oswald got to work, pumping medicines through IVs, pressing in tempo on Safadago’s chest, and breathing for him. This went on for a half-hour, on the pavement. Every two minutes, they shocked Safadago with a defibrillator.

“He was sure fighting throughout the call,” Ouellette said. “We shocked or defibbed him nine or 10 times.”

As the lead paramedic, Ouellette’s job was to supervise, while EMTs took turns doing chest compressions. Ouellette did not do any of the actual CPR or rescue breathing, he said. He is glad he didn’t recognize Safadago until later — trying to bring anyone back from the dead is stressful enough. This patient was unusual, for other reasons.

“With him, he was in a shockable rhythm every time we checked,” Ouellette said. “It just seemed like his heart was trying to fight back. I know that sounds cliche or corny, but he was fighting to come back. The heart either decides to come back, or it decides to go the opposite way.”

More firefighters showed up: three aboard Medic 25 and crews from Everett and South Snohomish Fire. Near the end of the lifesaving efforts, the paramedics shocked Safadago once more. They got a pulse. They loaded Safadago into the ambulance and put a breathing tube down his throat.

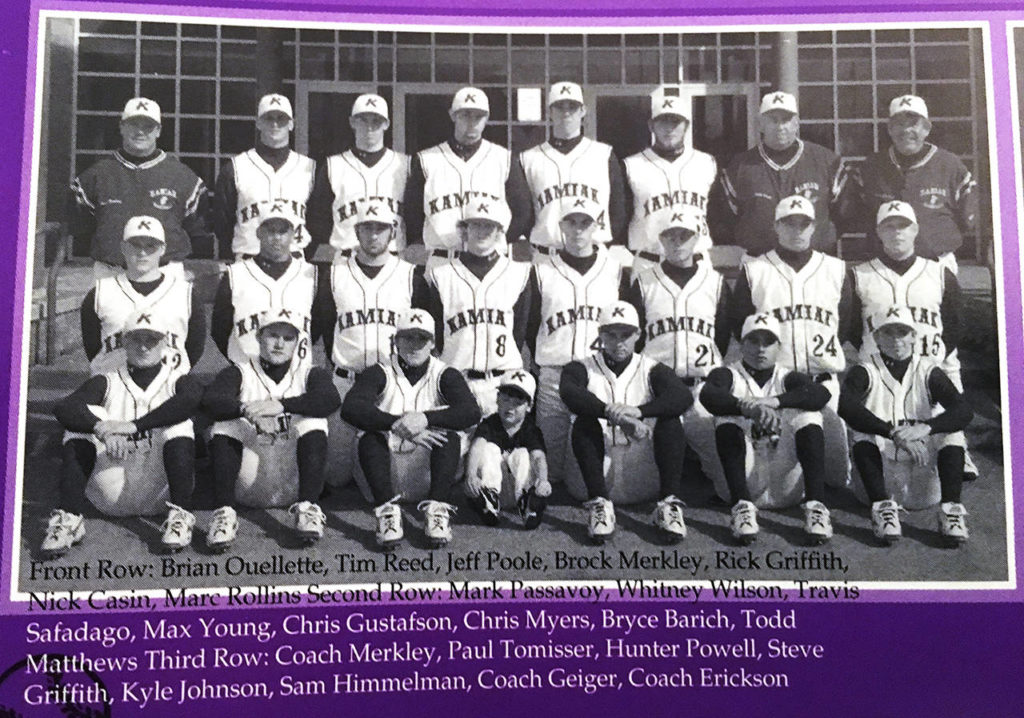

One of Safadago’s sons arrived at the scene. Ouellette did a double-take. He’d grown up down the hill from the Safadagos, where the boys, Justen and Travis, had a batting cage in the back yard. George Safadago had coached Justen and Ouellette on that fall ball team in 1997, and he had played baseball and wrestled with Travis at Kamiak High School.

Shoulder and elbow injuries cut short Ouellette’s baseball days at Gonzaga. He went on to become a paramedic, a career that took him to Ellensburg, Wenatchee and Sequim, before he landed back home in Mukilteo in 2016. That day in March, Safadago hadn’t seen Ouellette in ages. He didn’t know he had gone into the fire service.

“You don’t give too much thought about what they’re going to be doing 15, 20 years from now,” Safadago said. “But I’m glad about his choice.”

A save

Doctors at Providence Regional Medical Center Everett gave George a 15 percent chance of survival, his wife recalled. For the first two days, they put him into a drug-induced coma and cooled his body. Once he was warmed up, the family would give him 72 hours to respond. If not, they’d talk about what to do next.

The warming period seemed to take too long for Trudy. She went home at 12:30 one morning, exhausted. She actually fell asleep. Her phone woke her at 3 a.m.

“He’s squeezing my finger,” a nurse whispered.

George’s recovery went fast, for such a serious emergency. Once he was ready for food, he got a tuna sandwich. He scarfed it down so quickly Trudy thought he’d make himself sick.

George spent six days in intensive care, and a total of 10 in the hospital. He remembers almost none of it. Medical staff couldn’t find a clear reason for what happened — no blocked arteries, no plaque buildup, no real problems at all, other than a low heart rate and low potassium. George’s primary doctor told him later if he had to bet on any patient having a sudden cardiac arrest, he wouldn’t put money on him.

“It’s really awesome to have a second chance,” Safadago said, “and not even know that I needed a second chance.”

Since that day, he has a lot of people to thank: the witnesses who called for help from the Lodge, from a nearby dentist’s office and from the bus stop; the first-responders; and the doctors and nurses. The hospital gave him a pacemaker, to shock his heart if it ever stops again. He showed up at the fire station, to express his thanks to the firefighters who saved him.

“There were definitely guardian angels, through the whole journey,” he said.

Safadago still goes on walks. His doctor wants him to keep active. His wife is trying not to be a mother hen, she said, but she has timed exactly how long it takes him to cover three-quarters of a mile. The other day he was overdue texting her by four minutes. She panicked when he didn’t answer his phone. She called again. He picked up. He told her sorry, he’d bumped into somebody he knew. He’d stopped to chat and to enjoy life.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.