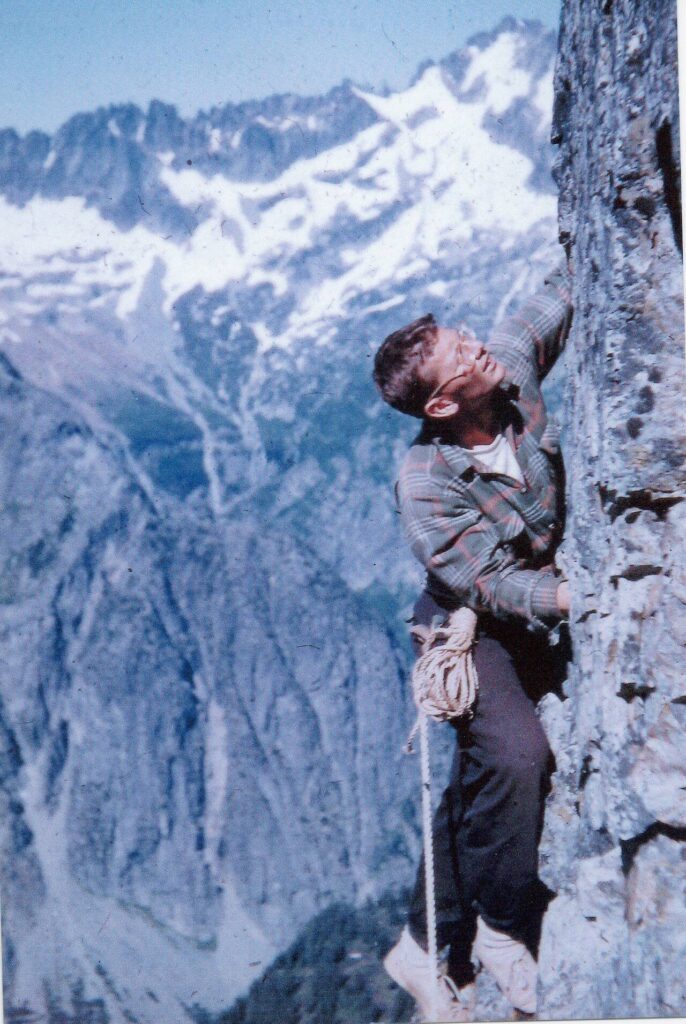

MOUNT VERNON — By the time he met his wife Lorraine in 1984, longtime Everett mountaineer Kenn Carpenter had summited over 650 peaks.

At least 15 of those routes — on Three Fingers, Silvertip, Bear Mountain and others — had never been done before.

He rarely told climbing adventure tales in the couple’s 40 years together, like his near-death experiences on Denali or bushwhacking on the descent from Mount Rainier.

Yet he readily shared stories from his time as a volunteer with Everett Mountain Rescue, “because it was not about him,” Lorraine Carpenter said in an interview this week. “It was about the person being rescued or about the team working together.”

Kenn Carpenter, of Mount Vernon, died of natural causes on May 6. He was 95.

His legacy, Lorraine Carpetner said, will be about more than his momentous climbing career, or the people he helped save in the North Cascades.

“Kenn will be remembered for the positive and lasting impact he had on the lives of the people who came into his sphere of influence, inspiring them to reach for the summit in their own lives,” Lorraine Carpenter wrote in a note about her husband.

Kenn Carpenter was born in Chicago on Feb. 10, 1929. He spent most of his young adult life in Philadelphia.

In 1953, Kenn Carpenter was working as a mechanical engineer at the Scott Paper Company in Pennsylvania when he transferred to the location in Everett — “for the mountains,” Lorraine said. He quickly joined the Everett Mountaineers. He was 24.

‘So that others might live’

Within his first year in Washington, he reached 50 summits: among them, the volcanos of Glacier Peak, Mount Baker and Mount St. Helens, decades before its pinnacle lost about 1,300 feet of elevation in a catastrophic eruption.

Kenn Carpenter usually ascended multiple mountaintops in a weekend. He meticulously and neatly documented the locations, elevations and dates of many of his treks in a small notebook titled, “Climbing in My Backyard: Trips and Adventures of Kenn Carpenter.”

In the 1950s, he led the founding of Everett Mountain Rescue. The volunteer organization would supplement Seattle Mountain Rescue, the only mountain rescue team in Western Washington at the time.

“The Cascades were so huge that one rescue organization was going to be stretched,” said Malcolm Bates, a mountaineer who interviewed Kenn Carpenter for his book, “Three Fingers: The Mountain, the Men and the Lookout.”

“I would imagine that he was one of those guys you are glad to see if you are in need of rescue,” Bates said. “I think his attention to detail extended to all aspects of mountaineering, not just route-finding, but rope management and first aid.”

In 1959, Kenn Carpenter directed more than 100 people in a mission to rescue a 9-year-old boy who was lost in the wilderness near Lake Bosworth. That same year, he descended into a 200-foot hole to save a state forester in the Sultan Basin.

The Everett Mountain Rescue Council nominated him for a “Citizen of the Year” award in 1959 for his rescue efforts — which he did on top of his full-time job at Scott Paper.

“This outstanding citizen of Everett has devoted many many hours of searching for lost people, and on several occasions risked his own life, so that others might live,” wrote Ralph Mackey, former chairman of the council, in the nomination letter.

‘In his DNA’

In 1961, Kenn Carpenter invited Robb Briggs, of Lynnwood, and several other U.S. Air Force members stationed at Paine Field to climb Mount Stickney, north of Gold Bar. Briggs had graduated from the Exum School of Mountaineering in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, then enlisted in the Air Force. Upon arriving in Everett, he heard whisperings from other climbers of a young man with impressive navigation skills on rock faces.

Briggs’ first climb with Kenn Carpenter sparked a decades-long friendship, filled with shared Pacific Northwest adventures and joint-rescue missions through Everett Mountain Rescue.

Not long after leading the group climb, Kenn Carpenter asked Briggs to join him in an ascent of the aptly named Mount Formidable, east of Marblemount. The trip took longer than the pair had anticipated, and once it got dark, they lost the trail. The next morning, they found their way down with the help of daylight and returned to Everett, Briggs said.

“We were always amazed with his ability to know exactly where he was in any desperate route-finding problem,” Briggs wrote in a letter to Lorraine, after her husband died. “We were lost. He never was.”

Kenn Carpenter was known to echolocate by yodeling during harsh weather. When the fog or snow cleared, “they found they were right where they were supposed to be,” Lorraine wrote in her remarks about her late husband.

“It was in his DNA, this understanding of the mountains and where he was,” she said.

Kenn Carpenter was detail-oriented and safety-conscious, Lorraine said. He studiously planned all of his adventures, leaving room for Mother Nature’s surprises.

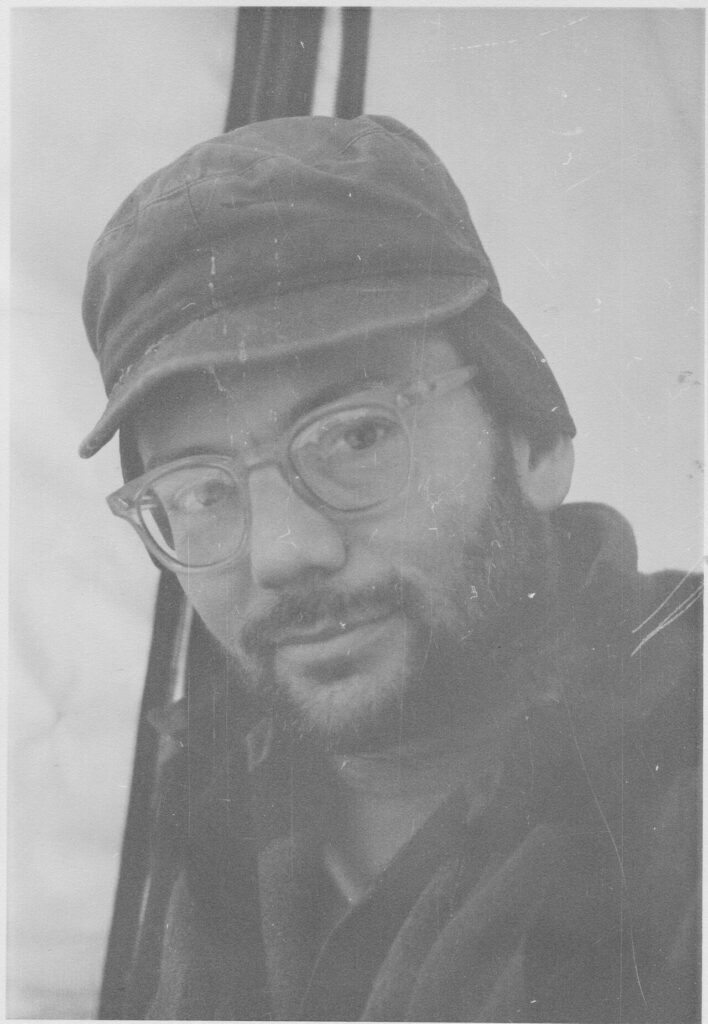

He attempted to climb Denali twice, back when it was known as Mount McKinley. During his second attempt in June 1962, he wrote in his journal: “We may not make it.”

A terrible blizzard engulfed him and three other climbers as they neared Denali’s summit. One member of the group got altitude sickness. Kenn Carpenter believed she would die if they didn’t turn around. Two climbers from the group made it to the top. Kenn and his friend Ron Miller helped the sick climber descend to safety.

‘To perfection’

In 1963, Briggs and Kenn Carpenter had “many close calls” during an attempt to climb Mount Robson in British Columbia, the peak with the most prominence in the entire Rocky Mountain Range. At 9,000 feet, an electrical storm prevented them from summiting. They collapsed their tent and huddled inside the flat shelter for hours.

“He was, to me, an enigma, in that he kept his thoughts and feelings private, even when the situation in the mountains could have gone either way,” Briggs wrote in his letter to Lorraine.

Big Four, at over 6,000 feet high, seemed to be his favorite, Lorraine said. He lovingly photographed the mountain covered in snow, with a clear blue sky as the backdrop. On his 34th birthday, he completed a first winter ascent of a route on Big Four.

In the 1970s, Kenn Carpenter’s climbing career abruptly ended due to a back injury. The injury happened before Lorraine met Kenn, so she wasn’t sure exactly when or where it happened. She understood that during a particular climb, someone in Kenn’s group got injured. He carried the climber’s pack, in addition to his own, for the rest of the trip.

Then within days of the climb, he bent over to pick something up, only to find he couldn’t stand up straight, Lorraine Carpenter said.

He found new avenues for adventure: bicycling, canoeing and running. In 1998, Kenn and Lorraine Carpenter biked across the country, starting in North Carolina and ending in Marysville, where they lived at the time.

Both the National Forest and National Park Service consulted Kenn Carpenter on conservation projects. His advice was instrumental in designations of the Boulder River and Glacier Peak wilderness areas in Snohomish County. He also helped map the Old Spanish National Historic Trail — a 2,700-mile route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to Los Angeles that Kenn and Lorraine biked four times.

Beyond his love for the outdoors, Kenn Carpenter was also a musician, artist, craftsman and mentor.

“Everything that he did,” Lorraine Carpenter said, “he did to perfection.”

“He was quiet, unassuming, gentle, kind, thoughtful and generous,” Lorraine concluded in her remarks about Kenn. “He was my hero.”

Ta’Leah Van Sistine: 425-339-3460; taleah.vansistine@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @TaLeahRoseV.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.