EVERETT — Boaters saw the body in the river on the first day of summer.

The current of the Snohomish pulled him downstream from Dagmars Marina on June 20, 1980. He’d likely been in the water for months, putting his possible time of death in spring.

He’d dressed in short sleeves, a tan cotton shirt with buttons and a white undershirt made by Healthknit, a fairly common brand in vintage stores today. Under a tangled pair of tan Big Mac coveralls, he wore blue swimming trunks with white stripes on the sides.

An autopsy revealed one of his final meals had a side of sliced potatoes, most likely French fries. They had hardly been digested.

Four decades later, his name is a mystery. How he ended up in the river is unknown. And we don’t know how far he was swept downstream. He could have been fishing, canoeing, tubing — or fallen in by some other random accident.

There was no obvious trauma, and no obvious cause of death.

On his death certificate, it was noted as an apparent drowning.

He’s one of over a dozen unidentified people whose remains have been found in the county since the 1970s. Last fall, he became the last of those to have his grave exhumed, when his weathered bones were lifted with his coffin from a cemetery in Everett.

Advances in genetic technology could help to identify him, if ever-shifting groundwater hasn’t done too much damage to his DNA.

Snohomish County cold case investigators are trying other means, too, to restore his identity and hopefully bring answers to his family.

Waterways

Two wild rivers, the Skykomish and Snoqualmie, spill out of the Cascade Range and fork together south of Monroe, to form the waterway that shares a name with the county.

Twenty miles downstream, the wide cloudy river washes into Possession Sound around the point where this John Doe was found.

Sheriff’s cold case detective Jim Scharf suspects the man had been snagged somewhere upstream for a while and broke loose, for some reason, around the time the boaters saw him.

Hydrological records show the river was not unseasonably high or low at any point that spring or summer.

Water can kill in any season.

Rivers run much higher and swifter in winter. In summer, people flock to them — and some drown.

The man is one of three unidentified people found dead in local rivers in 1979 and 1980.

One was in mudflats at the mouth of the same river, 1½ years earlier. A third was found by a teenager in the main stem of the Stillaguamish, near Silvana, in July 1980. All three men had been dead for a long time. All were clothed, with no apparent sign of foul play.

People have fallen or jumped into the Snohomish miles upstream and weren’t found until their bodies ended up drifting out toward Whidbey Island.

If someone hadn’t sighted the body floating in the river on that 73-degree day, that might have been this man’s fate, if he’d ever been seen at all.

Anatomy

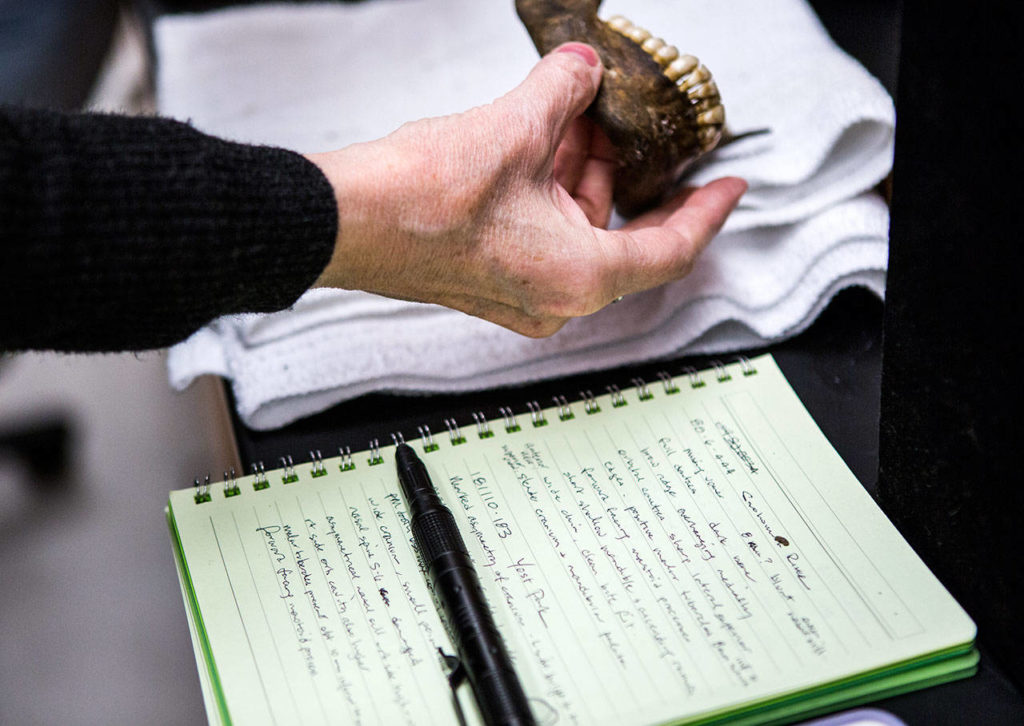

Handwritten notes in the case file describe the man’s features.

“Good teeth.”

He’d seen a dentist, Scharf said.

“160 pounds.”

That was his measured weight. He had a slender build and small hips, said Dr. Kathy Taylor, a state forensic anthropologist, when she made an initial examination of the remains in late 2018.

A listing on NamUs suggests he could’ve been as short as 5-foot-5, or as tall as 6-foot. His undershirt is the standard size for a men’s large tee. His coveralls came from JC Penney.

“20 to 30 years of age.”

That’s still a good educated guess, Taylor said. He could also be in his 30s.

Based on the skull’s shape, Taylor believed he was probably Caucasian. Maybe Hispanic. Almost definitely not Asian.

Old notes say he had brown hairs on his body.

Photos and film, however, were no longer in files recovered from state archives.

After the discovery in 1980, a woman contacted the sheriff’s office asking if it could be her missing brother. It was not him.

Often when bodies were found then, deputies checked to see if it could be missing Marysville man Titanic Hagen, who was last seen at age 26 in August 1979. Hagen appears to have been ruled out early on. He’s still listed as missing today.

Other missing people from that era may no longer be in police databases, since many records have been lost over the years. Cold case investigators encourage anyone with a missing loved one to check with the police department that took the report, to ensure they’re still listed as missing.

New digs

Time washed away whatever was on a tiny placard marking the man’s grave, by the time an excavator scooped out soft wet dirt in October 2018.

He’d been buried in a black casket with Gothic-looking handles.

Days earlier, the bones of another unidentified man were dug up in the cemetery. That man, nicknamed the Lynnwood Bones John Doe, was buried along with clothing — a shirt covered in cartoon flowers, a pair of pants, a vest — as well as deer bones that were found near his remains.

No coveralls, swimming trunks or T-shirts went into the ground with the Dagmars John Doe. Just bones. No shoes were found in the grave, either. On one faded evidence report, a box for the man’s shoes had been left blank. His footwear could’ve come off in the water, or he could’ve died barefoot.

Bones from his feet were set out on a table at the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office, along with everything else that remained of him.

A femur sample was sent to the University of North Texas in January, though it’s unclear if or when good DNA will be extracted. Investigators are awaiting a response from the lab.

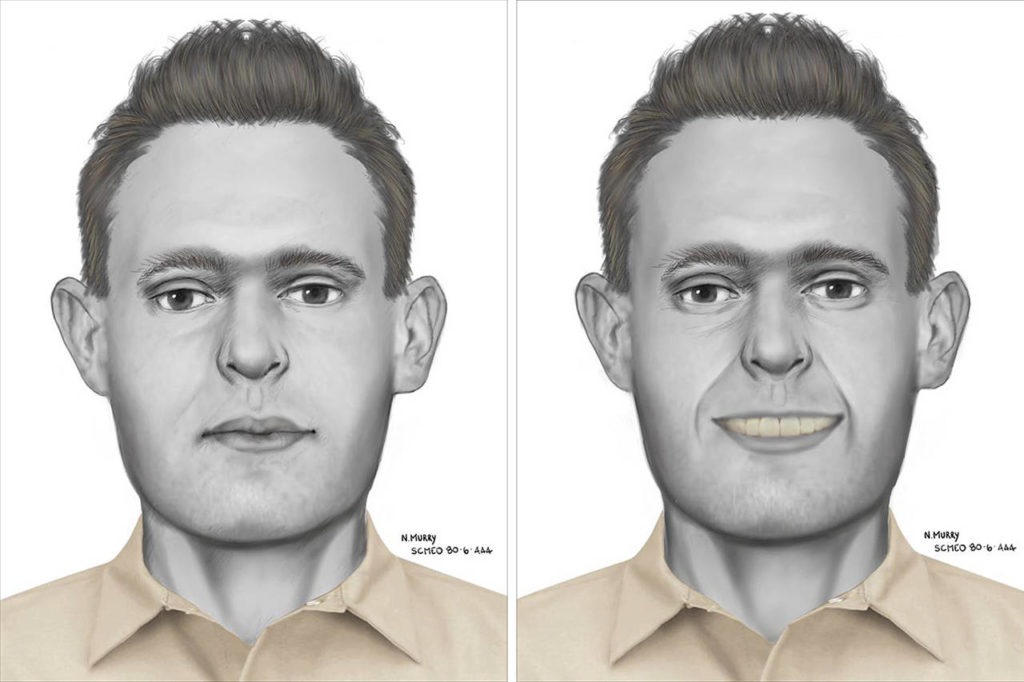

In the meantime, forensic artist Natalie Murry looked over the skull last month at the King County Medical Examiner’s Office. She glued rubber pegs onto the cheeks and forehead with Duco Cement to approximate the depth of his facial tissue.

Murry photographed the skull in front of a black backdrop, and put the pictures into a digital painting program. As his face came to life, she saw a right eye lower than the left, a crooked mouth that’s wider on the left side, and a strong brow ridge.

“The features all work in harmony,” Murry said.

Something in the nose, she said, will be echoed in another part of the face.

He had a full set of teeth.

Teeth are the only bones in the skull that we see in living people, Murry said.

So in one drawing, she showed him smiling.

Tips can be directed to the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office at 425-438-6200.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.