Jacob Peterson had it all ahead of him. With a degree from Seattle University and a job lined up, he was primed for a happy, successful life.

A heart transplant at age 6 gave him nearly 17 years more than he might have had. But Peterson’s life was cut short by medical crises related to his heart. He died April 10, surrounded by family, at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle. He was 22.

“He didn’t like people worrying about him. He was a really selfless kid,” said Jacob’s father, Jamie Peterson, who lives in Stanwood. “He didn’t like any kind of negativity. He was just a good person.”

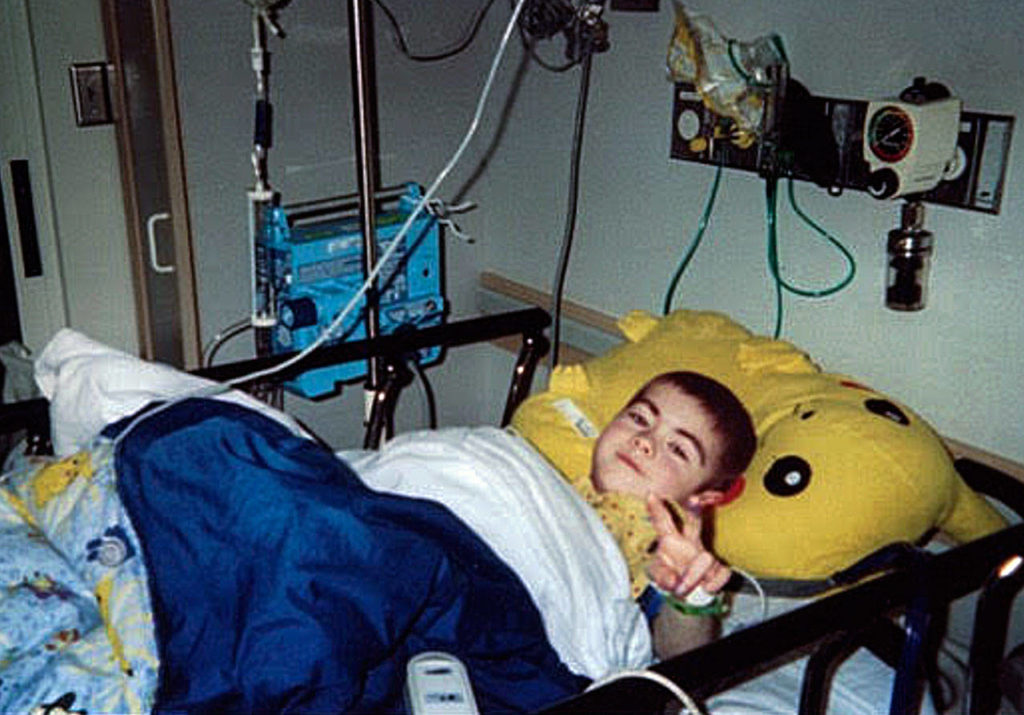

Jacob was a Lakewood Elementary School first-grader when I visited the family’s north Marysville home in 2000. At 3, a checkup had detected a heart murmur. He was diagnosed at Seattle Children’s Hospital with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a disease affecting the heart muscle.

Medication kept him stable until he was 6. As his condition worsened, he was in constant need of an oxygen tank. His activities were severely limited. On a wait list for a donor heart, the call came at last. His transplant surgery was Dec. 14, 2000, at Seattle Children’s.

“He has lots of energy,” his mother, Carrie Peterson, told The Daily Herald in August 2001. “It’s done, over with, and he’s moved on.”

And move on he did, graduating from Lakewood High School in 2012 before earning a bachelor’s degree in marketing at Seattle University’s Albers School of Business and Economics.

In high school, he took part in drama for four years. “He was Peter Pan his senior year,” Carrie Peterson said.

Jacob’s parents divorced, and both are remarried. Carrie Peterson now lives in Everett. Jacob also leaves his brother, 21-year-old Jeremy Peterson.

Jacob Peterson loved video games, his parents said, and did live video streams. As “jakepeter” on YouTube’s gaming channel, he had 10,844 subscribers. He also created clever short films for YouTube under the name “JakeHasAnApple.” One of them, “Kiss Me I’m Single,” has had more than 35,000 views.

A self-described “Nintendo fanboy,” his favorite game was Pokemon and his favorite character was Mew.

With his “go-getting attitude,” Carrie Peterson said, her son had big goals. “His ultimate goal was to work for Nintendo,” she said. Jamie Peterson said his son was ready to start a good job with Geico in Renton. He had been living in Stanwood with his dad, but planned to move to Seattle.

His family knew Peterson’s transplanted heart likely wouldn’t last for decades.

According to research released at the 2014 meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, 54.3 percent of pediatric heart transplant patients in a study group survived at least 15 years past surgery. Dr. Hannah Copeland and colleagues at California’s Loma Linda University reviewed records of 337 pediatric heart transplant patients whose surgeries dated back to 1985.

“Pediatric heart transplant is not a cure but a chance at life,” Copeland wrote in the study, which was provided Thursday by the UW Medical Center.

Jamie Peterson said his son’s health had been mostly stable since the transplant. “He was kind of a model case for a long time,” he said.

Carrie Peterson said Jacob had recently suffered from fatigue. “By the time he went to the doctor’s appointment a few weeks ago, it was already too far along in rejection,” she said.

After a stress test at UW Medical Center, he spent two weeks there. Jamie Peterson said it was possible his son needed a second heart transplant, and also a kidney. Anti-rejection medication is hard on kidneys, he said.

Both parents said there are dangers for young adults who had serious medical issues as children.

“He didn’t like to share symptoms,” said Jamie Peterson, who hopes to launch an awareness campaign. “In that transition from childhood to adulthood, young people think they’re invincible. They’re trying to be independent.”

Carrie Peterson, who encountered young HIV patients as a social worker, said that as kids reach legal adulthood they sometimes “stop taking meds — they’re sick of it.”

The Peterson family hopes to save lives through education, perhaps enlisting older mentors who can share their experiences with lifelong medical issues.

On Saturday, Jacob Peterson’s family and friends will gather at Seattle University for a private memorial in his honor. They ask that in lieu of flowers, people donate to Seattle Children’s Stanley Stamm Summer Camp. Jacob had worked as a counselor at the camp, which serves kids with chronic medical conditions.

“As a father, I’m just so proud of what a good person he was,” Jamie Peterson said. “He lived every day to the fullest.”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

How to help

Donations may be made in memory of Jacob A. Peterson to Seattle Children’s Hospital Foundation, Stanley Stamm Camp, P.O. Box 5371, Seattle, WA 98145.

Or donate online: https://giveto.seattlechildrens.org/changealife. A drop-down on the form allows a designation for Stanley Stamm Camp, and donors may note that a gift is made in Peterson’s memory.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.