By Dominic Gates / The Seattle Times

SEATTLE — Boeing’s contract with the Machinists who build the jets in the Renton and Everett assembly plants runs out in 10 months. The union leadership is preparing now for a high-stakes confrontation — with a careful eye on the successful tactics of the autoworkers union in Detroit.

For two decades, Boeing has repeatedly wielded threats to send work out of state that have forced concessions and weakened the historically powerful International Association of Machinists.

This time, labor is resurgent nationwide and for the first time in 16 years the IAM’s 30,000 Boeing employees in District 751 have leverage they lacked in the previous two contract rounds.

After 10 years of wage stagnation, IAM members certainly expect to win a huge pay increase, as high as 40% over four years. Another priority is to head off future threats to move jobs elsewhere by demanding that Boeing commit to build its next new jet in the Puget Sound region.

“It’s a massive point in time,” said District 751 President Jon Holden. “This is going to impact our members in this community for decades to come.”

If Boeing balks at the IAM’s demands, it could face a damaging strike that would seriously set back its attempts to recover from the crises that have staggered the company over the past four years.

In an exclusive interview, Holden said he hopes to reach an agreement without a work stoppage but added “we’re prepared to strike if we have to.”

“You have a right to stand up and say no,” he said, “That’s the power of the labor movement.”

Holden indicated the union is considering the aggressive and highly effective new tactics of the United Auto Workers. This fall, the UAW forced big contract deals with the three major Detroit automakers by striking at selective plants instead of having the entire workforce walk out at once.

“We’re watching the UAW negotiations and strike very closely,” Holden said. “They’re doing some very creative things.”

This raises the novel prospect for Boeing of a similar tactic that could see many IAM members continue to work and be paid while selective stoppages cripple key jet programs, say the 737 MAX, where the planned production ramp-up is essential to Boeing’s cash flow, or the 777X, where major customers expect 2025 airplane deliveries after waiting years for their new widebody giants.

“There’s some possibilities,” Holden said pointedly. “We don’t all work in the same plant. We don’t all work the same job. We don’t all work on the same program.”

Formal negotiations will begin in January or February and will gain intensity as 2024 unfolds.

The IAM has already scheduled a big “prepare to strike” rally at T-Mobile Park in Seattle for July 17, where they will hold the vote required to sanction the possibility of a strike.

Boeing’s deadline is the current contract’s expiration, at midnight Sept. 12.

Labor power on the rise

Around the country, amid acute worker shortages following the mass retirements and employment shifts during the global pandemic, labor unions are exercising power they haven’t had for years.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics lists 22 major work stoppages in the U.S. so far this year. Hollywood writers and health care workers staged successful strikes. UPS offered employees a big pay increase to avert a strike.

The aviation world is particularly hobbled by a shortage of workers throughout its supply chain and in the airline ranks.

After a short six-day strike in June, Machinists at financially strapped Spirit AeroSystems in Wichita, Kan., a major Boeing supplier, won 31.5% pay increases over four years, plus cost of living adjustments and a $3,000 signing bonus.

Holden called that a “springboard” for his negotiations.

Without striking, the pilots at American, Delta and United this year won big wage hikes over four years of 46%, 34% and 40% respectively. After a big contract pay increase last year, Alaska Airlines pilots got another major raise this year to bring their pay closer to that of the bigger carriers.

“Labor has the upper hand for the first time in decades,” said industry analyst Richard Aboulafia of consulting firm Aerodynamic Advisory.

In aviation, “the magic number that seems to appear just about everywhere is about 40% over four years,” he said. “That’s the market rate.”

Speaking on CNBC late last month, Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun commented on the surge in strikes.

“I don’t like what I see,” he said. “Only because everybody gets hurt. Nothing really good comes of these moments. So it’s up to all of us to try to avoid them with everything we’ve got.”

Calhoun declined to speculate on whether Boeing will be able to avoid a strike. Instead, he simply praised the workforce, citing how they carried Boeing through the grounding of the 737 MAX and its return to service in late 2020.

“We love the workforce. They do a phenomenal job,” Calhoun said. “I have enormous respect.”

Bitter defeat last time

Yet the Machinists don’t see respect in the last two contract rounds.

In those, Boeing initiated negotiations midcontract with the threat of building a new plane somewhere else if the union didn’t agree. Still working under contract, in those talks the union didn’t have the option to strike.

In 2011, the union agreed to higher health care costs in order to secure the 737 MAX for the Renton assembly plant.

In 2013, “only about a year and 10 months later,” Holden said, relations took a much worse turn when “they then threatened us again with moving the 777X somewhere else.”

Those 2013 negotiations took a dramatic and bitter turn after the Machinists voted that November to reject Boeing’s offer.

The national IAM leadership led by then-International President Tom Buffenbarger and his lieutenant Rich Michalski — presumably convinced that management wasn’t bluffing, and that future jobs and union dues would be lost — worked to overcome the wishes of the local machinists.

After further Boeing threats, the national IAM arranged a second vote for Friday, Jan. 3, 2014 — knowing that some of the higher-paid machinists had already booked that as an extra day off to extend New Year vacations out of state.

With some more militant senior machinists absent for the vote, Boeing squeaked through with 51% accepting the contract.

With that, the 777X stayed in Everett. But the Machinists were tied into a contract for a decade with very substantial concessions.

They lost their traditional pensions, replaced by 401(k) plans; they settled for wage increases of just 4% over a span of 8 years; and the company shifted health care costs further onto employees.

“Our members have never forgotten this,” said Holden. “That’s where the anger comes from.”

Aboulafia called the 2013 contract drama “a master class in … how to alienate your workforce.”

The bitterness of that IAM defeat, and what was viewed locally as a betrayal by the national leadership, ripped the union apart and led to a change in the union’s constitution that’s critical to the coming negotiations.

Local 751’s then-President Tom Wroblewski retired immediately, crushed by the intensity of the fight against both the company and the national union.

Holden, 51, took his place. Growing up in Bothell, he’d heard tales of union power from his dad, a Teamster, and his grandfather, who was an autoworker in Detroit.

After Buffenbarger retired in early 2016, at the union’s Grand Lodge Convention that fall his successor Robert Martinez joined with Holden and District 751 to pass a constitutional amendment so that midcontract talks can never happen again without a vote of the full membership.

So in 2024, the union will hold very different cards than in 2013.

This time, Boeing has no new airplane in the works; Calhoun has said he won’t launch an all-new plane until toward the end of the decade. So there’s no available threat to move jobs.

Once the contract expires, the union will have its normal legal right to strike.

And Boeing is in a precarious position.

Its executives have repeatedly told investors that by late 2025 or early 2026 Boeing’s business will have recovered from its current loss-making depths to something approaching normal.

By then, Boeing projects, the pileup of parked 737 MAXs and 787 Dreamliners awaiting repair will be cleared and jet production will ramp up to produce a gusher of cash: $10 billion of free cash flow per year, versus about $3 billion this year.

“That’s going to be because of delivering the 737s at a much higher rate,” Holden noted. “That’s only going to happen because of the workforce here and the infrastructure that’s here in Puget Sound.”

A strike in the fall of 2024 would seriously stall Boeing’s trajectory toward recovery.

“We have our full leverage. We have our full power,” said Holden. “And we will be successful.”

What the union wants

The rank-and-file IAM members sense that 2024 will be a turning point.

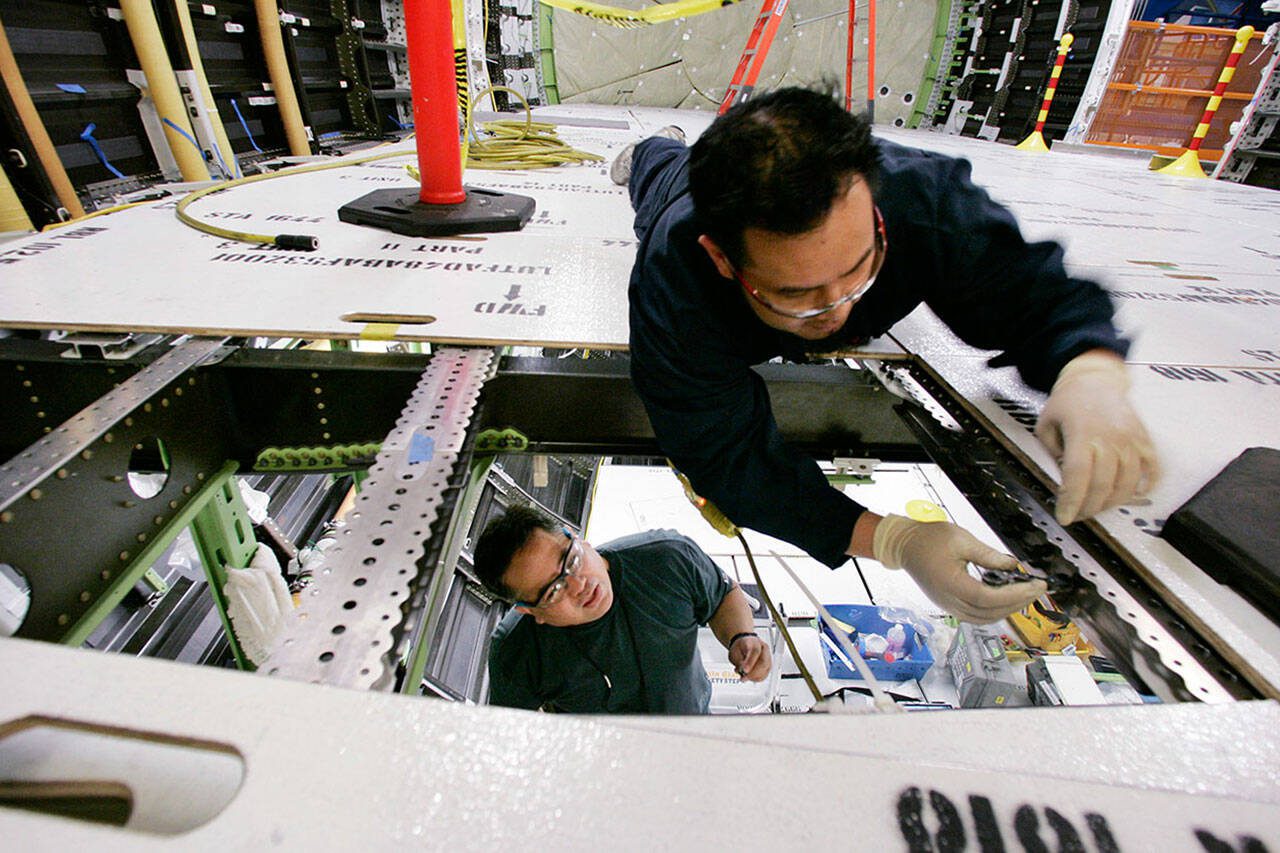

Everett union steward Brendan Mann, a paint team lead inside the 777X composite wing manufacturing center, said in an interview he feels his co-workers are “very determined.”

“Everyone’s talking about it,” he said of the coming contract. “And everyone is very positive.”

The October edition of the District 751 union newspaper quoted Secretary-Treasurer Richard Jackson saying: “The members are hungry for change … I am excited to see their passion.”

To establish priorities, the union has been surveying its members and found them eager to claw back some of what was lost in 2013. Analyst Aboulafia thinks that’s to be expected.

“They’ve really taken a hit over the past few decades and this is the first time in a very long while that they have the power to get some of that back,” he said.

Because of the pressing need to hire mechanics, Boeing this year raised its new-hire rates so that the lowest-level mechanic will start at $23.50 an hour.

And after six years at the company, Boeing machinists get boosted to a maximum pay rate of between $40 an hour and $51.30 an hour, depending on the job skill grade.

While IAM members expect the wage rates to be raised substantially in the coming contract, Holden said many are also asking him to try to get the defined-benefit pension back.

“I hear it every time I’m in the factory,” he said.

Aboulafia doubts Boeing would agree to that. He said American corporations have largely abandoned traditional pensions, which create a fixed cost that cannot be reduced and becomes a burden in a business downturn.

Holden clearly recognizes that’ll be a big lift, but he’s going to ask for it.

He noted that the Machinists’ work, physically tiring and often entailing exposure to toxic chemicals, takes a toll.

“Our members love the work they do, but it can be very tough,” he said. “Our members deserve retirement security. … It’s tough stuff on our bodies.”

If Boeing cannot accede to restoring the defined benefit pension, it will have to offer hefty improvements in 401(k) plans and retiree medical benefits to compensate.

“The reality is we have to get retirement security and it comes in many forms,” said Holden.

And Holden says younger Machinists, many of whom were hired after that 2014 contract defeat, want in addition something that’s grown in importance to today’s generation: a better work-life balance through an end to mandatory weekend overtime.

Yet perhaps the IAM’s most ambitious goal in the coming negotiations is something Boeing has always refused to offer: an advance commitment to build its next new jet in this region, ensuring jobs decades into the future.

“We’re going to make it part of bargaining. We have no choice,” Holden said. “We need jobs for 50 years, not four years.”

Again, Aboulafia thinks the company could balk at that.

Calhoun’s public statements suggest the launch of a new jet is five or six years away. Aboulafia wonders what legal enforcement mechanism there could be to hold management to such a promise that far ahead.

As a consultant, Aboulafia has worked for the union to produce a state-by-state analysis of aerospace competitiveness that placed Washington at No. 1. He counsels caution.

He says that while the winds are right for the IAM to win a great contract, it should beware of being too adversarial and overplaying its hand.

A realistic and pragmatic goal, Aboulafia said, is for the union leaders to “get a nice healthy increase in the here and now” and then to “look toward a partnership” with management for the future to try to keep Boeing competitive.

Which path will the union take and how will Boeing react?

One rank-and-file Machinist, who works on the 777 and 777X — and who asked not to be named because he’s not a union official and so risks his job by speaking to the press without company permission — said he’s convinced Boeing will cave to avoid a strike and give the IAM a very good contract.

The company has too much at stake, he said, as it promises impatient investors it will ramp up jet production, generate cash and return to financial viability.

Yet the 777 Machinist also succinctly expressed the bitter legacy of the contract talks 10 years ago.

“Out of principle, I feel we should just strike,” he said.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.