By Stephen L. Carter / Bloomberg Opinion

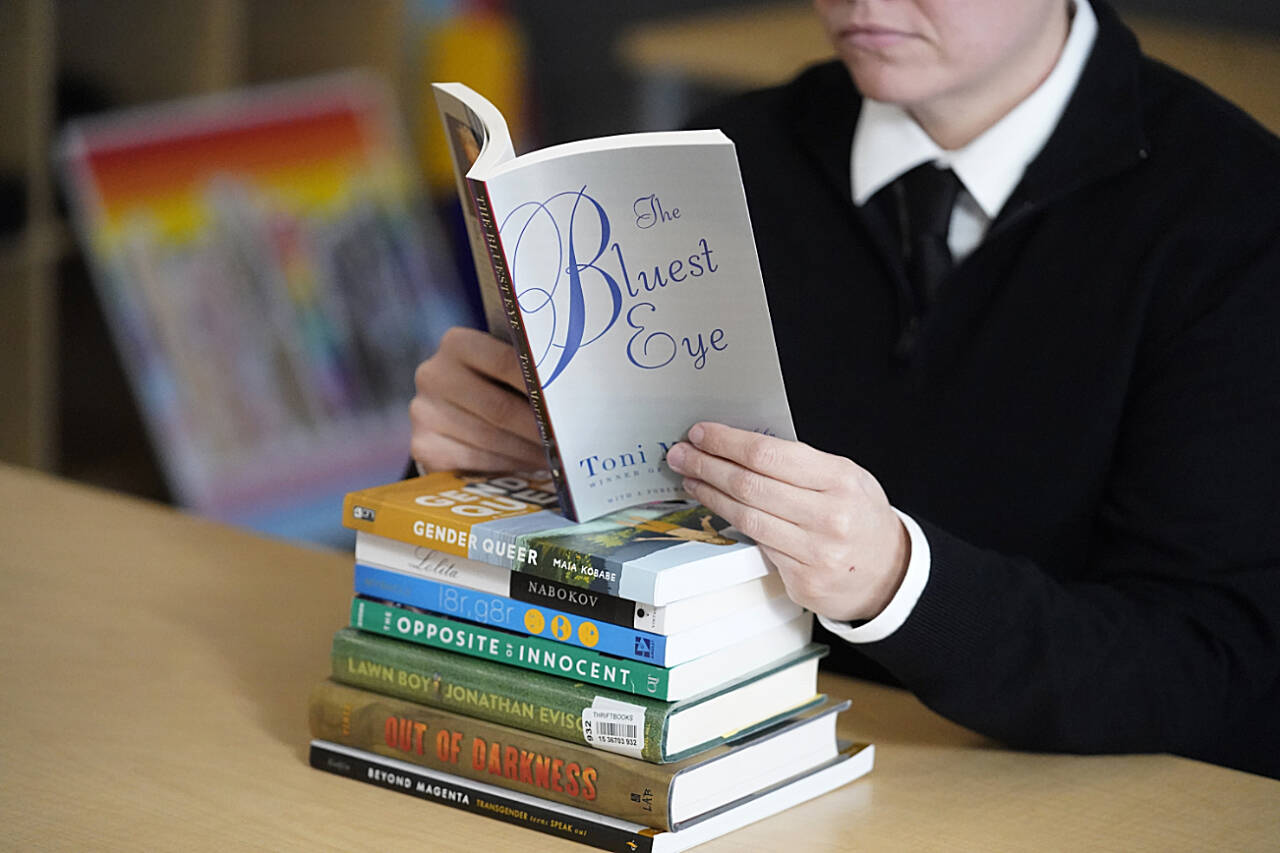

Banned books are back in the news. This time around they include not only the usual suspects (Toni Morrison, “The Diary of Anne Frank”) but also the Bible (“any variation”) which, we’re told, was written by “Men who lived a long time ago.” All are on the list of volumes plucked from library and classroom shelves in the Keller Independent School District in Texas, where a newly elected board of education has decided to move every book that’s been recently challenged, even by a single person, to the library’s “parental consent area.”

This is not, technically, book banning. Pending the implementation of a new policy on how to handle challenges, the volumes can still be accessed, as long as the students have a parent’s permission. Still, I’d suggest that the district is handling a genuine concern in the worst way possible.

I’m against book burning. Er, banning. In principle, I suspect that just about everyone is. But the instinct to keep certain tomes out of the hands of the young is ever-present. It stems from the same source as the equally ever-present instinct to keep dangerous ideas away from adults.

A lack of trust in potential readers.

Keeping truth from the masses: The journalist Ian Leslie, in his excellent book on the importance of curiosity, argues that popular accounts of Galileo’s battle with the Catholic Church misunderstand the moral of the story: “It wasn’t that the church was incurious about the true nature of the cosmos; it’s that they believed such knowledge should remain the exclusive province of those who were able to handle it; that is, people like themselves.”

In particular, the church was angry that Galileo published his findings not in Latin but in Italian. Everybody had access.

Oversimplification of a complex event? Perhaps. But the claim also states a literal truth. In order to condemn Galileo’s views, the inquisitors first had to read them. Their own minds obviously weren’t changed; but they worried that others would be. They distrusted potential readers.

I’ve long argued that when we speak of what adults can access, acting on this mistrust — even in so high-sounding a cause as protection against “misinformation” — represents an affront to democracy. But a degree of worry makes sense when we’re speaking of young children of impressionable mind. How we handle that distrust is what leads to so many controversies.

With kids, our sensible habit is to increase their knowledge bit by bit. We don’t teach calculus in kindergarten. (Though maybe we should.) And few if any parents want their children to read every book that sits somewhere in the house, say nothing of the school.

‘De-selecting’ books: In general, I trust parents to make judgments about what their own children should be exposed to. The practical problem is implementation. The public school should certainly respect my desire to shield my own kids from a particular book. But my concerns about what my own children should read is hardly an argument to remove the offending volume from the curriculum. Certainly my fears shouldn’t be enough to force the school — in the current argot — to “de-select” the book.

Nowadays, schools are pressured from across the spectrum. There are religious parents who want to control how sexuality is presented to their kids, there are parents of color who worry that their children will come across offensive words, there’s even a librarian who was fired for allegedly burning books by Donald Trump and Ann Coulter.

But although parents should take an interest in what their children read, Keller’s new board of education has the solution exactly backward. In a library the default should be availability, not unavailability. No special archive requiring parental permission should exist. Parents should have to opt children out, not in, perhaps via a digital popup during the checkout process. Absent a parental choice, however, children should be permitted and even encouraged to wander the shelves library as they please.

Feeding kids’ curiousity: The young are naturally inquisitive. We might call them curiosity machines. Leslie quotes the psychologist Michelle Chouinard: “Asking questions is a central part of what it means to be a child.” When they’re small, they ask for information. As they grow older, “their questions become more probing”; they want explanations. Even in our days of diminished interest in books, a library remains a place where the young should be free to give rein to their natural and proper desire to know.

True, no library can include everything. Choices have to be made, and they will always reflect the political culture of the era. I remember from my own youth the many patriotic books lining school shelves. I also recall how a massive volume grandiloquently titled “The Human Body: What It is and How it Works” turned out to offer little information on how babies are made. Even the classics were often bowdlerized to avoid any mention of sex; an act of literary vandalism of which I was unaware until college, when I read the unabridged versions.

Such choices, however well intentioned, represented an effort to restrict young people to a particular view of what matters, even of what they should think or believe. But a library’s job is exactly the opposite; to expand not limit children’s understanding of the world and its possibilities.

Stephen L. Carter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A professor of law at Yale University, he is author, most recently, of “Invisible: The Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.