By Theresa Vargas / The Washington Post

A bird feeder.

A vase of paper flowers.

A collection of tiny ceramic llamas.

These are just a few of the objects that people have created or collected during the pandemic and know, even as they stand in it, will long remind them of what they have experienced during this time.

Several days ago, I wrote about the stuffed panda my 6-year-old son persuaded me to sew, despite my lack of sewing skills, and posed a question: What tangible thing, whether it be sentimental or funny or practical, will represent your mile marker for this moment?

I recognize that we are far from over this global crisis. Too few people have received the vaccine (my 78-year-old father is among those who haven’t), and too many people will remain on unsteady ground even after they get those shots.

So, when I tossed out that question, I wasn’t asking anyone to look back. I was asking people to look around them.

And many of you did.

In recent days, I have heard from people across the country about objects that didn’t exist in their lives before the pandemic and now occupy a prominent place in them.

They described things they made by hand, for themselves and for others, and things they purchased to get through days of boredom and months of mourning.

They told of things they have tucked away in drawers, and things that sit unmissable in their living rooms.

In a home in Gaithersburg, Md., a tree covered in butterflies stands near one filled with ornaments that represent different holidays. Gail Fallon calls the latter a “tree for all seasons” and the one with butterflies “an expression of hope.”

She explains in an email their significance: When she realized her family couldn’t get together for their annual Christmas Eve gathering, she decided not to decorate a tree. Later, she felt sad about not bothering, so she decorated two trees and decided to leave them up until her children and grandchildren could safely visit.

“They’ll be amazed and delighted,” she writes. “In the meantime, we have a nightly smile when the trees light up and we anticipate happier times.”

Outside a home in Philadelphia hangs a bird feeder that Theresa Conroy bought in June, a time she describes as coming “after three months of lockdown, the agonizing death of my mother from cancer, the closing of my yoga studio and the continued longing for my dead dog.”

In an email, she tells of throwing herself into researching which feeder to buy, where to place it and what to put in it. Within days of hanging it, she says, birds swarmed. She has seen sparrows, cardinals, nuthatches, chickadees and, on occasion, a woodpecker her family has nicknamed Woodrow.

“We steeped ourselves in bird behavior, bird songs, seed preferences and their imagined conversations. For hours. And hours,” she writes. “So, a plexiglass tube filled with black sunflower seeds is what’s getting me through a deadly pandemic.”

We have all experienced this past year differently. Many of us have lost someone, and some of us have felt lost. Others among us have discovered new skills and goals.

The items people chose as marking this moment for them are unique in that each carries a different story, and yet many strike at universal sentiments. In emails, social media posts and the comments section of my earlier column, people describe items born of grief, isolation and longing.

They tell of graves they now visit, “plague year puzzles” they have completed and letters from children who feel too far away, not because of distance, but because of circumstances.

An Anthony S. Fauci bobblehead.

A tandem kayak.

A “love notes” sweater.

A homemade Santa cutout.

A TV journal created by someone who used to rarely watch shows.

If we had a communal time capsule for the pandemic, those are just some of the items people would toss in it.

Mary Ann Heavey of Fairfax, Va., picked as her pandemic item “Corona” the cat. She made the mask-wearing stuffed feline for her grandson, who was “feeling the pangs of the pandemic and the need to wear a mask.”

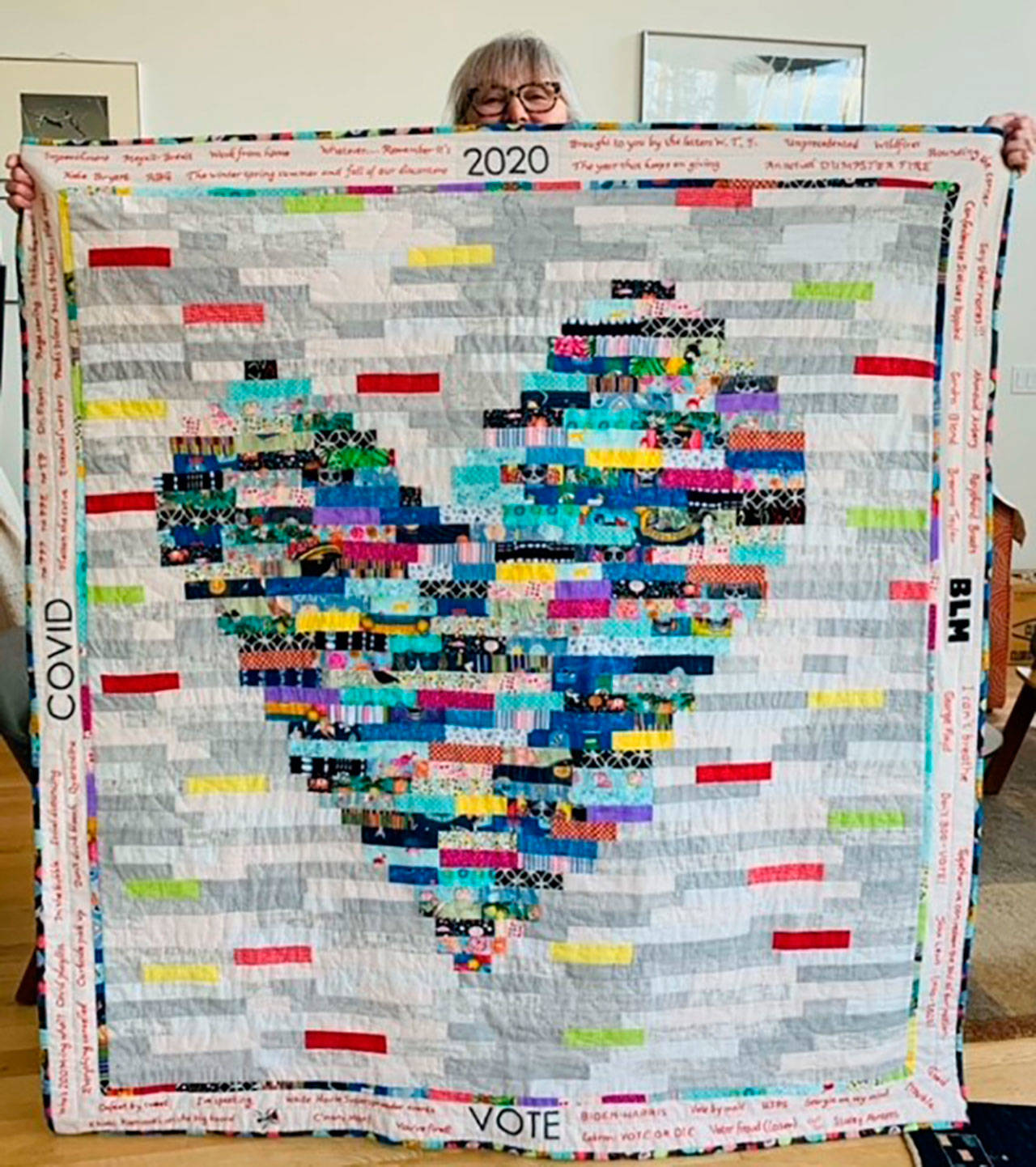

Judy Walsh of Maine chose as her object a quilt she made using leftover fabric from the more than 1,000 masks she sewed as she “cried and hollered.” The quilt contains nods to the Black Lives Matter movement, the pandemic and that fly that landed on Vice President Mike Pence’s head. “As I worked on it,” Walsh says, “it became a record of all we had lived through in 2020 — all the mess.”

Mary Schaller keeps a vase of crepe paper flowers in her Springfield, Va., living room. On March 13, she was in Dominica, celebrating her 77th birthday, when her husband bought three from a woman standing on the shore. Later, at dinner, her tablemates gave her two more. Nearly a year later, she says, they have not faded, and they remind her of “the last day of ‘Normal.’ “

“I’m looking forward to our next day of ‘Normal,’ ” she writes in an email, “but in the meantime, I have these lovely flowers to remind me of a happy time before the pandemic and the promise that happy days will come again.”

I don’t have the space to tell you about all the items people described, and it’s a collection that unfortunately will only grow larger as the pandemic grows longer. But one item seems particularly poignant for a pandemic time capsule. It involves a lot of figures that were broken but not destroyed.

In February, Liz Jimmerson-Alaeddinoglu of Seattle was pursuing her master’s degree in teaching. In the spring, she started creating small ceramic llamas by hand, making one each day she went without seeing her first-grade students in person.

By the time the season ended, she had created 108.

“I finished the project in the summer as I completed my master’s and graduated by myself in my living room,” she writes in an email. “I installed a shelf in my living room to keep the finished llamas. That night, when I was out at the grocery store, the shelf fell and all the llamas broke. I sobbed for days.”

She glued them back together, she says, because there was nothing else she could do.

“I’m still heartbroken,” she says.

She also still hasn’t seen any of her students in person.

Theresa Vargas is a local columnist for The Washington Post. Before coming to The Post, she worked at Newsday in New York. She has degrees from Stanford University and Columbia University School of Journalism.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.