By The Herald Editorial Board

In what might have been a practice run for the 2024 election, an unknown individual or group interfered with the Nov. 7 election by sending envelopes — at least some of which contained traces of fentanyl, and messages demanding an end to the election — to election offices in five Washington counties.

The discovery of the envelopes and concerns over exposure to a potentially dangerous contaminant led to the evacuation of affected offices and a temporary halt to ballot counting in those counties.

A similar suspicious envelope was received by Snohomish County’s election office, but — noticed after news broke of the envelopes sent to King, Skagit, Pierce and Spokane counties — it was left unopened and turned over to investigators with the FBI. Similar envelopes were received in Oregon, California, Nevada and Georgia.

While fentanyl cannot cause poisoning or overdose from contact, the mailing of white powder echoed threatening mailings in the days that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, in which anthrax, an infectious bacteria, was sent to members of Congress and several media offices, killing five people and sickening 17.

Even if nothing more dangerous than baking powder was included in the envelopes, the intention to cause panic and interfere with the election is clear. Nor is it hyperbole to consider the mailing of the letters an act to elicit fear, as described a day after the election by Secretary of State Steve Hobbs.

“These incidents are acts of terrorism to threaten our elections,” Hobbs said in a news release, and called for action to protect election workers and elections themselves.

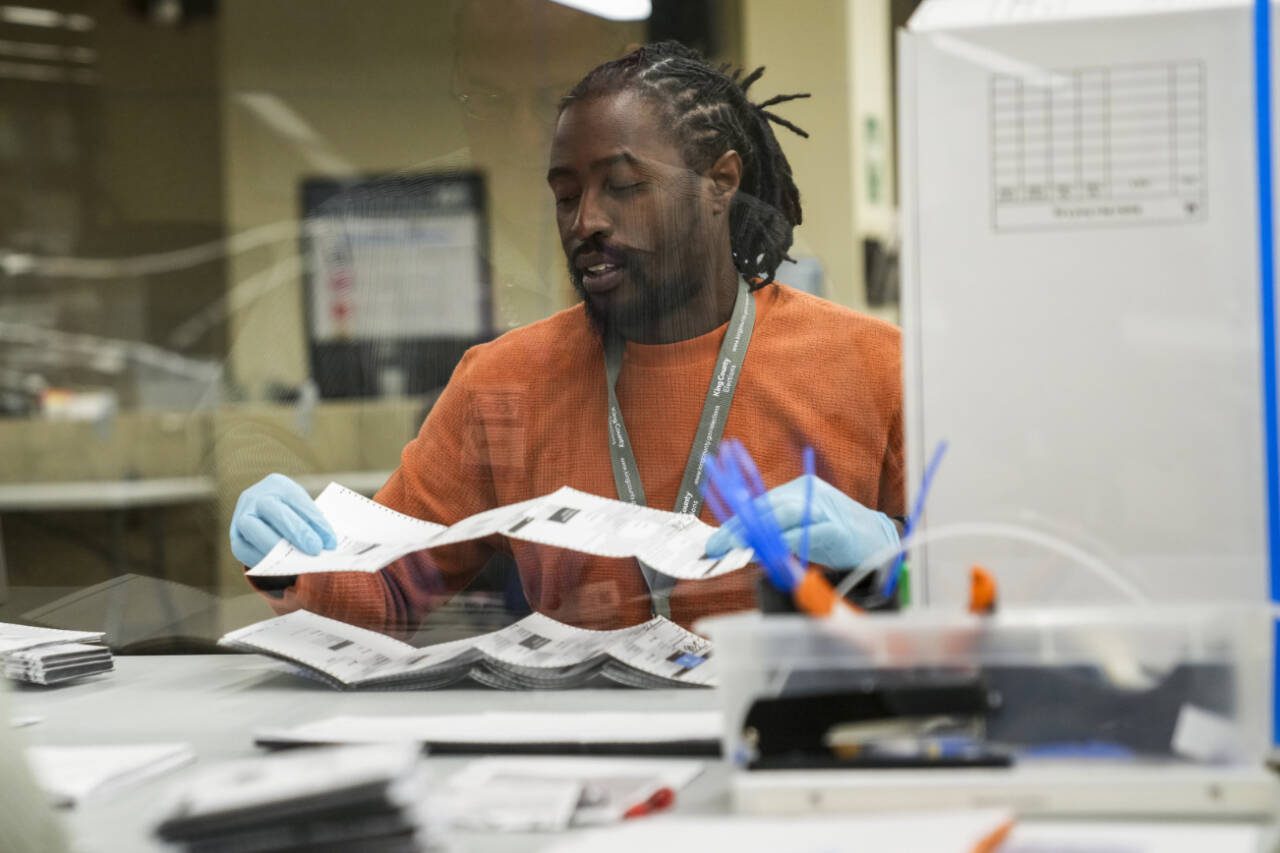

“The safety of staff and observers is paramount as elections workers across the state open envelopes and count each voter’s ballot,” he said. “These incidents underscore the critical need for stronger protections for all election workers. Democracy rests upon free and fair elections.”

These weren’t the first such threats made to elections staff in Washington state. A threatening email was received by an election worker during the August 2022 primary in Jefferson County, at its election office in Port Townsend, warning: “Be careful … your life may depend on it. The truth will prevail,” The 19th, a nonprofit newsroom reported earlier this year.

Earlier in 2022, the Legislature changed the state’s law to rename cyberstalking as cyber harassment, making it a felony to send an electronic communication that would cause a reasonable person to suffer emotional distress or fear for their safety. The law specifically mentions harassment of a staff member in elections and criminal justice offices, performing their official duties.

While the person sending the email was identified, the county prosecutor did not file charges, noting the state law required threats to be more specific to get a conviction. However, the election worker was able to obtain a five-year restraining order against the person who sent the email.

Those same protections, especially for election workers and volunteers, should be extended to include all forms of communication. Legislation has been proposed before; and in fact, was passed by the state Senate in 2021. That legislation, Senate Bill 5148, would have made harassment a Class C felony, when directed against a staff member of the Secretary of State’s office or that of a county auditor’s office. But the legislation did not advance in the House in 2021 or 2022; and a similar House bill did not advance this year.

State lawmakers should take up that bill again, and look at other potential protections and fortifications for the election process, including additional funding for county election offices to protect worker health and safety.

With another consequential election less than a year away, those protections and reinforcements must happen early in the coming session.

The Institute for Responsive Government, a nonprofit policy group that works for election and other reforms, has previously awarded Washington state a B grade in its state-by-state election policy rankings, and considers it one of the “top-tier” states, noting its past accomplishments regarding voter registration, restoring voting rights of the formerly incarcerated and vote-by-mail system.

But in general, the institute finds states’ elections offices lacking in protections for their workers.

“This is a workforce that’s one of the most sort of underfunded, under-resourced, overworked public service jobs that exists in the United States,” Sam Oliker-Friedland, the institute’s executive director, told The 19th. “And it’s one that’s primarily women. I don’t think that’s an accident.”

While not as bloody and violent as the attempted insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 2, 2021, which was intended to halt Congress’ official recognition of the results of the 2020 presidential election, the mailings sent to election offices in Washington and other states were interference with the election, laced with the threat implied with white powder.

Directed at this state’s and other states’ administration of elections, each letter was an act of terrorism focused on those workers who provide the most fundamental service to voters and to our democracy.

Those workers deserve our appreciation and the state’s protection.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.