By The Herald Editorial Board

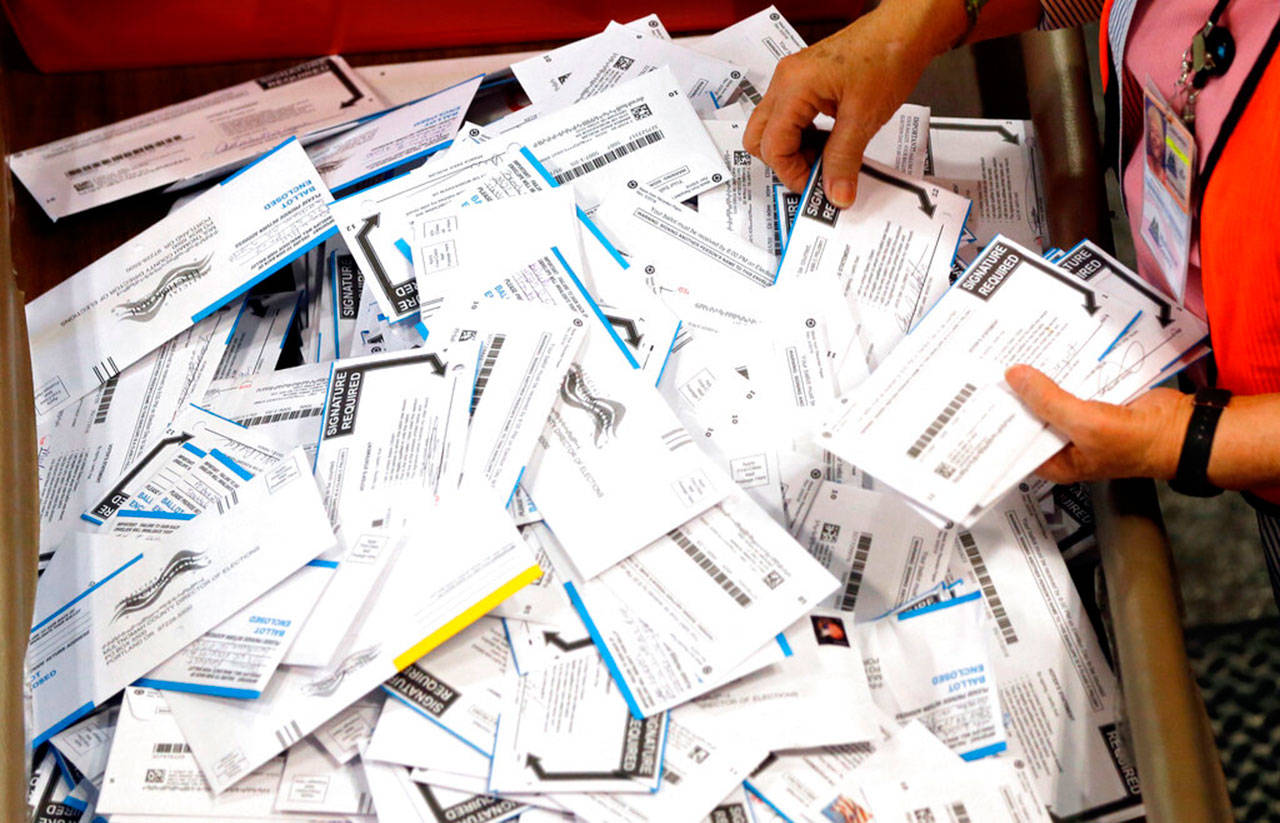

The justifications for opposing vote-by-mail elections — especially amid continuing concerns about how long stay-at-home orders will remain in place or whether they might return this fall during the coronavirus pandemic — continue to fall away, like chad from an old-school paper-punch ballot.

President Trump prompted headlines — and discomfort among some fellow Republicans — last month when he was asked about measures to ensure voters’ ballots could be cast and counted during the pandemic, including vote-by-mail, early voting and same-day voter registration.

Where some Republicans have opposed such measures by casting them — without proof — as invitations to voter fraud, Trump was blunt — transparent, even — regarding his problem with making voting more accessible, even during a pandemic: “(I)f you’d ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again,” he said during an appearance on “Fox & Friends,” repeating the conventional wisdom that increased voter turnout favors Democratic candidates.

However, Trump and others opposed to vote-by-mail because of a perceived advantage for Democratic Party candidates need not worry. There simply is no partisan advantage for either party by allowing voters — as the president now does himself with an absentee ballot for his Mar-a-Lago, Florida, address — to vote at home and mail in their ballots.

A study published this week by political scientists with Stanford University’s Democracy & Polarization Lab affirms earlier research that has found no benefit to either party when a state switches to universal vote-by-mail, The Washington Post reported Thursday. The study concludes that vote-by-mail doesn’t affect either party’s share of turnout or votes, but does encourage a modest increase in voter turnout overall.

Allowing for county-level differences, the study found “a truly negligible effect” on partisan turnout rates. The study’s reliability in affirming earlier research is bolstered by its inclusion of data from the 2018 midterm elections.

But knocking down any apprehension of a partisan advantage isn’t itself going to lead to a national drive to adopt vote-by-mail and other voter-access provisions that Washington state and four other states have already made law, not even with the state of chaos that the coronavirus pandemic has threatened to throw this year’s elections.

It’s just not likely that those states that haven’t already begun the transition to vote-by-mail can make the switch in time for the Nov. 3 election.

Just ask Washington state Secretary of State Kim Wyman, a Republican, who has spent her tenure since winning her first election to that post in 2012, shepherding the state through a slate of changes to improve voter access and fine-tune a vote-by-mail system that allowed counties to go to all-mail elections in 2005 and was adopted statewide in 2011.

Wyman and her office have been in high demand for advice among fellow election officials, advising all 50 states on vote-by-mail issues, she told The New York Times this week. She’s been encouraging but straight forward.

“I don’t think it’s a realistic goal to think that you could get 50 states to all be vote-by-mail by even the November election just because the states are in such wildly different places,” Wyman said. “There’s some states where it would be an easy transition to just go to vote-by-mail, and I think there’s some states where it’s going to be a very heavy lift.”

To protect the health of voters, what can be done in states where vote-by-mail isn’t widely offered would be to increase the availability of traditional absentee ballots for those voters who are most at-risk to the coronavirus outbreak, while making changes at polling places that ensure social distancing guidelines can be followed.

Even so, those limited changes will require a greater investment by states for ballot postage, acquisition and distribution of ballot drop boxes, vote-counting equipment and facilities and confirmation of voters’ addresses and signatures.

Congress, as part of the $2 trillion CARES Act, included $400 million to assist states with their elections during the pandemic. That level of funding will likely be exhausted quickly. Another $500 million in grant funding has been proposed in legislation co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-1st Congressional District.

But even Washington state voters can’t now assume that they’ll be able to vote by mail later this fall. That could depend on whether the U.S. Postal Service will still be around to deliver the ballots.

While thus far the addition of “pandemic” to snow, rain, heat and gloom of night have not stayed these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds, the agency is facing dire new budgetary difficulties because of the drop the pandemic has forced in the volume of first-class and marketing mail that provides the bulk of its revenue, impacts that have only worsened decades-long financial troubles for the agency.

Congress attempted earlier to include assistance in the CARES Act, The Washington Post reported last week, but the Trump administration reportedly threatened to veto the act all together if it included some $13 billion in aid intended for the post office. What the Postal Service was allowed in the end was a $10-billion line of credit, money that must be paid back.

Without the loan, which still must be approved by the Treasury Department, the Postal Service wouldn’t have the cash to continue operations, including pay for its 600,000 employees, after Sept. 30, a month before the general election.

Reforms for the Postal Service and for elections are worth discussion, but with uncertainty lingering for each because of the pandemic, actions are needed immediately to protect both American institutions.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.