By The Herald Editorial Board

It’s now up to Washington’s state Supreme Court to get out a box of Crayolas and “Draw Your WA,” completing the task of drawing new congressional and legislative districts for the state, after the bipartisan redistricting commission failed last week to adopt new maps before its deadline at midnight Monday.

The court — with congressional and legislative elections next year, and uncertainty for incumbents, potential candidates and for voters and residents waiting to hear which districts represent them — will need to make its decisions led by fairness but with deliberate speed.

At the same time, the redistricting panel’s commissioners will need to explain — not so much their inability to complete their process before the deadline — but for their apparent violation of state Open Public Meetings Act in the final hours of their deliberations.

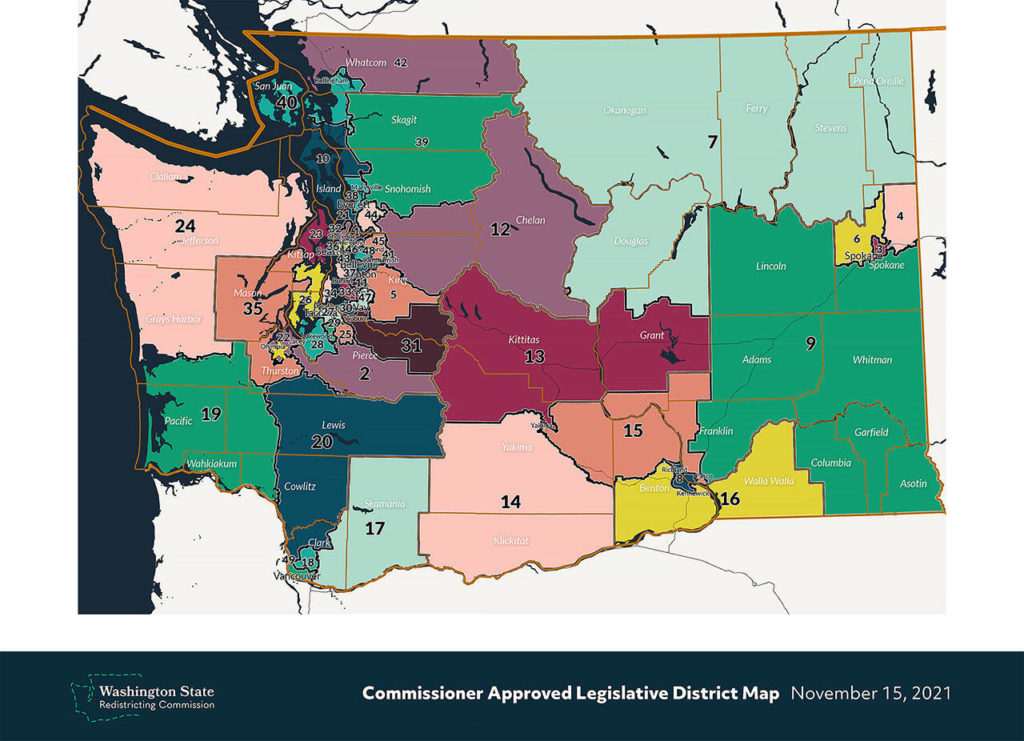

Following the federal 10-year census, states redraw their legislative and congressional districts to reflect the shifts in population that have occurred over the decade. For Washington state that means redrawing the boundaries for 10 congressional districts for the U.S. House of Representatives and 49 state legislative districts for the state House and Senate. Those boundaries must shift, primarily, to keep districts at relatively equal populations.

Prior to the last four censuses, those decisions had been left up to state lawmakers — and typically the party in the majority — as it remains the practice for many states, which has left those states open to charges of gerrymandering, drawing districts to benefit the party in power. Since the early 1980s, however, the task of redistricting in Washington state has been handled by a five-member commission, with two members appointed by Republicans in the Legislature, two by Democrats and a fifth nonpartisan and nonvoting chair.

To approve maps, three of the four commissioners have to agree. But this time — for the first time since the commission process was first used in 1991 — the four commissioners were unable to reach agreement on the two maps by the deadline. As provided in state law, the nine-member state Supreme Court now has until April 30, 2022, to approve or amend the maps. That means a potential timing squeeze for incumbents and candidates. Candidate filing for the 2022 elections for all Congressional House races, all state Houses races and a 24 of the 49 Senate races begins May 16 and concludes May 20.

Along with some shifting boundaries for Snohomish County legislative districts, some in Snohomish County could find themselves in completely new congressional districts, including the 8th Congressional District, which under the panel’s final plan includes much of the county’s eastern communities, previously in the 1st District.

Confusion remains over what the commission accomplished Monday night. The four members appeared to have taken a final vote just before deadline to adopt agreed-upon maps, but then initially declined to release the maps or provide much comment or context immediately after the vote.

Almost a full day later, the commission released the maps Tuesday evening, but confessed it had missed its deadline; what had been voted on prior to midnight Monday was a “framework” for agreement, rather than a final agreement.

The commission, admittedly, was working with a compressed timeline. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau had been delayed by the pandemic and by the meddling of the Trump administration during the census. As well, a change in state law moved up the commission’s deadline from the end of the year to Nov. 15. The commission also cited technical problems.

Recognizing its failure, however, the commission now is asking that the Supreme Court — rather than starting from scratch — pick up where the commission left off and review and approve the panel’s final maps.

There’s reason to start work there, not so much out of respect for the commission’s work, but for appreciation of an impressive effort by state residents to participate in the process, commenting on concerns about their districts, on proposed maps and even submitting their own maps.

Commission Chairwoman Sarah Augustine, in a statement Tuesday, noted the contribution made by those providing comments at 17 public outreach meetings and 22 business meetings, the public testimony of more than 400 residents, 2,750 comments regarding draft maps and more than 3,000 emails, web comments, letters and voicemails. As well, using the commission website, more than 1,300 maps were created, of which 12 were considered as third-party proposals.

Rather than duplicating that work, the court should use the commission’s final product as a starting point for its review and consideration.

At the same time, the court’s process should attempt to make up for the commission’s lapse in transparency in its rush to reach agreement before deadline. The court cannot simply rubber-stamp the commissions’ maps.

In its final hours, little of the commission’s deliberations were carried out in public session — broadcast over an online teleconference — as is required by the state’s Open Public Meetings Act, a law that applies to all state and local governments. Rather than deliberate in open session, the two party caucuses met separately in executive session, skirting the law’s quorum rules, and attempting to reach agreement through “straw polls” outside of public session.

The commission’s actions have drawn criticism from government transparency advocates and at least one lawsuit.

“It clearly seems as is if this was a deliberate attempt to essentially hide the discussions from the public,” Mike Fancher, president of the Washington Coalition for Open Government, told The Seattle Times. The state Supreme Court also is looking for some explanations, ordering the commission’s chair to provide a sworn declaration by Monday that outlines the panel’s actions and votes of Nov. 15 and 16.

Even if the court can indeed use the commission’s final maps, the commission’s violation of at least the spirit of the open meetings act should not be ignored, in particular because the work of redistricting goes to the very foundation of our democracy: elections and representation. The state’s redistricting commission has rightly been held up as a model for other states that have been dogged by charges of partisanship and gerrymandered districts. Violation of the open meetings act now tarnishes that hard-earned reputation.

The state Supreme Court should employ a review of the maps and their underlying data and public comment that is open and fully transparent, so that fair and representative districts are assured and that faith in a democratic process is restored.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.