By The Herald Editorial Board

Criticized at the start of the year by newspaper and open government watchdogs over the latest attempt by some state lawmakers to get around the state law regarding release of public records, legislators — rather than commit to complying with the law — have now introduced bills that would weaken the 50-year-old law; not just for themselves but for all state and local government agencies and their officials.

The state Public Records Act, made law by citizen initiative in 1972, requires release of public records at all levels of government and by public officials related to the work performed on the public’s behalf. The law’s reasoning goes that in delegating the people’s authority to its representatives, the people have not forfeited the right to transparency in government.

State agencies and local governments — from state departments to cemetery districts — are required to be responsive to requests from the public and the media for documents and information that is created in the course of government work. Yet, state lawmakers have resisted over the years when media and citizen watchdogs have requested documents, specifically emails, correspondence, text messages, schedules, draft legislation and more.

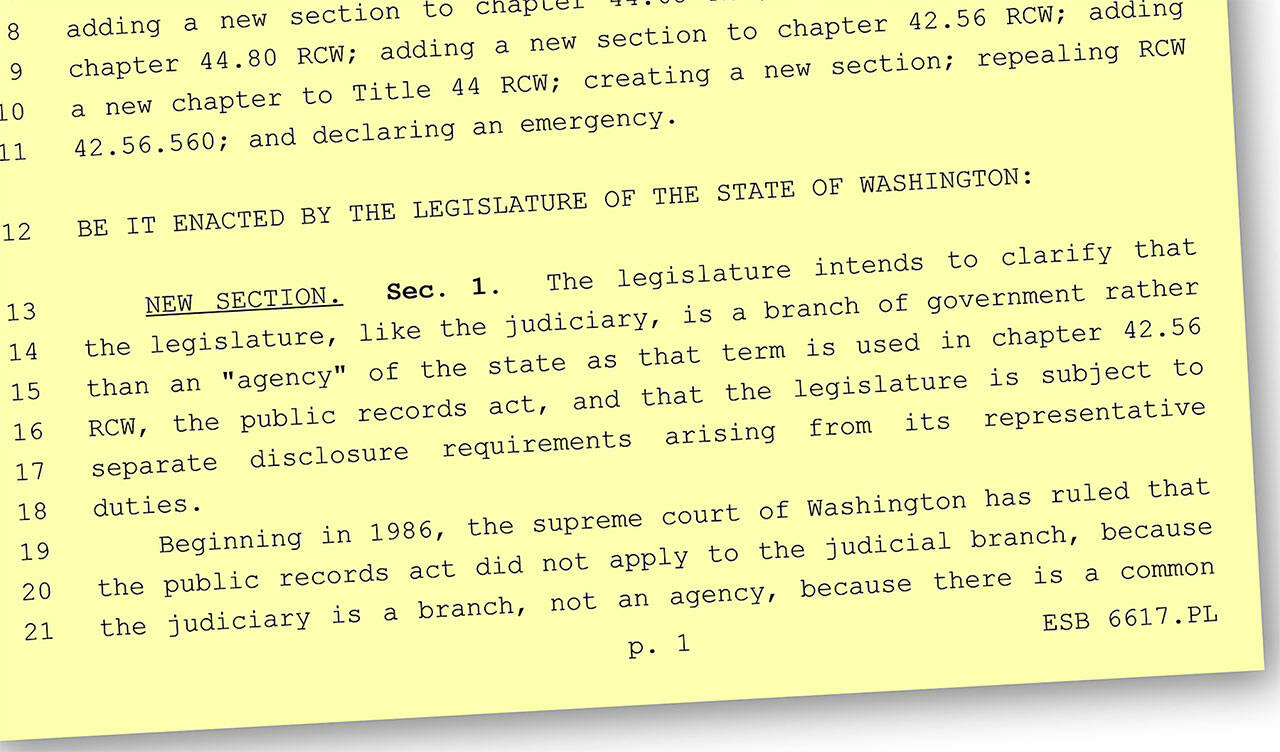

This despite a 2019 state Supreme Court ruling that affirmed that the “plain meaning” of the Public Records Act applied to the Legislature’s elected representatives and its offices, a ruling that followed a lawsuit over lawmakers’ vetoed attempt the year before to largely exempt themselves from the act.

Rebuffed by the court, lawmakers in select instances had floated a new theory they could deny requests by claiming “legislative privilege,” a dubious exemption that has now been challenged with a lawsuit in Thurston County Superior Court.

Not content to wait for the law to be reiterated for them once again, lawmakers have proposed bills in the House and Senate that would complicate the process of the Public Records Act and could encourage foot-dragging and outright denial of release of records by state and local governments and officials.

House Bill 1597 and its companion Senate Bill 5571 would give agencies more time to respond to requesters appealing denied records request; force record requesters to jump through a series of administrative hoops before filing suit over a denial; cut the time for filing a lawsuit by half to 180 days; allow courts to penalize requesters and award those penalties to agencies; and require requesters to certify their requests are not for “any improper purpose.”

The problem with the legislation, responds the Washington Coalition for Open Government, a nonprofit advocate for government transparency, is that it will complicate and lengthen the process and give governments more time to consider records appeals but reduce time for requesters to take disputes to court.

As well, requiring requesters to certify their requests aren’t for “improper purposes” could be easily abused by officials seeking to accuse journalists and citizen watchdogs of harassment to avoid releasing potentially embarrassing information.

Local governments and others have complained in the past that some have used the Public Records Act with little interest in the public good, seeing an opportunity to file suit and win damages if an agency fails to respond to requests in a timely fashion. Rep. Amy Walen, D-Bellevue, a cosponsor of the House bill, told a reporter for McClatchy newspapers that a total of $7.2 million was awarded to records requesters in 133 court claims in 2021.

While some have used the act in the past as a cottage industry to profit off the mistakes of local governments, Walen’s account of court awards doesn’t provide a break-down of which were malicious and which were legitimate requests. The purpose of those fines is to ensure responsiveness from governments regarding records requests.

Judges, the open government group points out, already have discretion to ferret out frivolous requests and court challenges and can impose fines against requesters and attorneys who are abusing the act for personal gain instead of public good.

Other than being referred to each chamber’s committee on state government, neither bill has advanced or been scheduled for a public hearing before committees. But lawmakers may be holding the bills in reserve until later in the session. In 2018, lawmakers introduced the bill to largely excuse themselves from the act in the final 48 hours of that session, passing it without a public hearing and without debate.

And one lawmaker, Rep. Gerry Pollet, D-Seattle, with a record of responsiveness on public records expressed concern regarding the bills to the McClatchy reporter:

“I’m worried that the Legislature is going to be at war with the right of the public and news media to get public records this year,” Pollet said. “Putting an obstacle in front of full and honest disclosure is never in the interest of democracy.”

There is reason to clamp down on bad actors using the act’s provisions for harassment or personal gain, for the sake of taxpayers and the sake of the Public Records Act, itself. But weakening the act — as the proposed legislation would do — detracts from its purpose of government transparency and accountability.

Neither bill should proceed any further.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.