By The Herald Editorial Board

Continuing the series of Why We Can’t Have Nice Things — like a Congress that functions under some degree of bipartisanship — are recent calls to redraw the maps of states’ congressional districts ahead of the 2026 midterm elections; to secure either party’s control of the U.S. House of Representatives.

With a slim 219-212 Republican majority in the House — and the typical happenstance that the president’s party loses seats in Congress during midterm elections — Republicans in Texas, Missouri, Florida and possibly elsewhere are looking to redraw congressional maps to increase the size of those states’ Republican delegations, giving them a better shot at holding on to the House, going into 2027. Usually, such redistricting is done in the year following the annual U.S. census, but Texas Gov. Greg Abbott called a 30-day special session last week that, along with approving needed flood relief, would, at the urging of President Trump, redraw maps mid-decade that could give Republicans up to five additional seats, increasing that delegation to 30 Republicans to Democrats’ eight members.

With their Democratic base poking party leaders with a stick and telling them to do something, Democrats — among them House Minority leader Hakeem Jeffries, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker and New York Gov. Kathy Hochul — have discussed the potential to counter the GOP redistricting effort with their own re-redistricting of those and other blue states, including Washington state, launching a Gerrymandering Summer Olympics.

To their credit, state Democrats — who control both legislative chambers — appear to have the sense and the clarity of vision to see that such an effort here wouldn’t offer much of an advantage and wouldn’t get far even if it did.

“There’s literally no way to get the results they are talking about before the 2026 election,” said Senate Majority Leader Jamie Pedersen, D-Seattle, told the Washington State Standard last week. “We have already done our share to get Democrats in the House. There’s no juice to squeeze in the lemon here.”

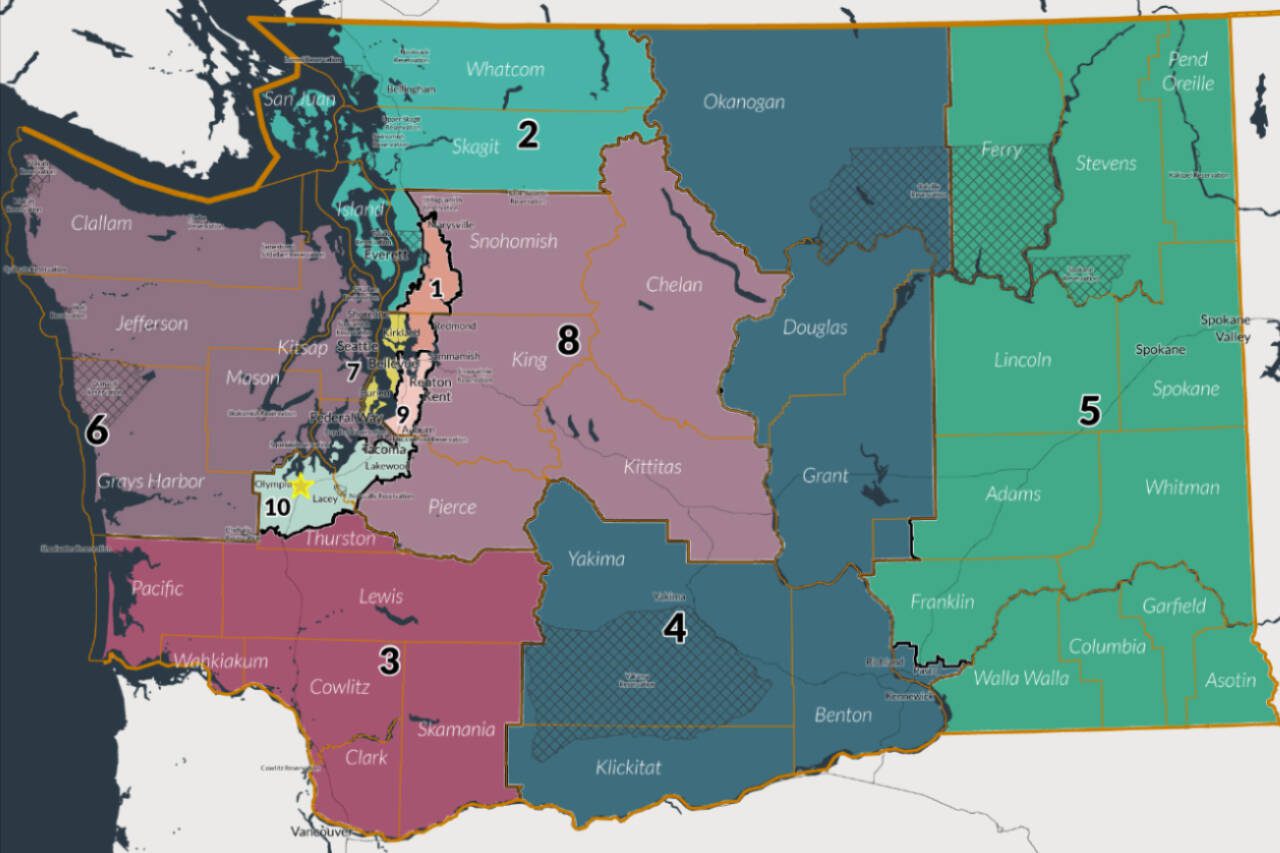

Democrats currently hold eight of the 10 congressional districts, and have done so fairly. Democratic and Republican state lawmakers agreed that it would take substantial effort and a convolution of current districts to force even one more Democrat onto the delegation.

And it would come at the cost of eroding much of the existing trust that state voters have in the current bipartisan redistricting process. A long history of legislation and lawsuits led to the creation in 1983 of the current process: a bipartisan commission that meets after every 10-year national census of five members: two members selected by Republican lawmakers, two by Democrats and a non-voting chairperson, who is selected by the other four members. Three of the four voting members must agree on the final boundaries for districts, with the Legislature able only to make minor adjustments to the maps. If the process isn’t complete by a deadline the state Supreme Court has the final say on boundaries.

Washington is among four other states with similar commissions. Four others have independent commissions. Most of the rest are controlled by the party in control of the state legislature.

Commissions, either bipartisan or independent, are seen as the best path to eliminating partisanship in the map-drawing process and assuring fair representation, a “federalist approach,” according to Princeton University’s Gerrymandering Project. The project’s most recent Redistricting Report Card gave Washington state an A grade for its congressional redistricting on the strength of its partisan fairness and composition, geographical features and minority representation and an overall B grade for its state legislative redistricting on the same measures.

Likewise, a similar group, Coalition Hub for Advancing Redistricting and Grassroots Engagement, gave Washington a B-minus for the latest redistricting effort, giving it good marks for the process and its improved representation of tribal communities and a collaborative and open process, but marking it down for two failures:

A lack of transparency that occurred when the commission, with its deadline approaching, took the process behind closed doors and issued its final maps without releasing them prior to adoption; and

Failing to adequately serve Latino communities in the Yakima Valley, which resulted in a lawsuit that required a judge to redraw legislative district boundaries there.

The state Supreme Court heard an appeal in the case in March and is expected to issue a decision later this year.

While, happily, there appears to be no interest in reopening the process to partisan gerrymandering, there are improvements state lawmakers can make — and time to pass reforms before the next census — that will assure even higher marks and better representation.

To its credit, the Legislature in 2022 did consider two reforms, both of which passed the Senate but did not advance to floor votes in the House. One would have put down in writing that the public be given ample opportunity to review and comment on new maps and boundaries before final approval. Another would have required pre-clearance by the state Office of the Attorney General for any changes to election and redistricting laws.

Yet another suggestion would remove the parties from the process altogether, appointing nonpartisan citizens to the commission.

All should be considered next session as campaigns ramp up for the midterms.

Texas, California and other states can fiddle with boundaries as they will, risking further disgust among voters who want fair representation rather than partisan gamesmanship.

This Washington can set itself as a better example.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.