By Tyler Sperrazza / The Washington Post

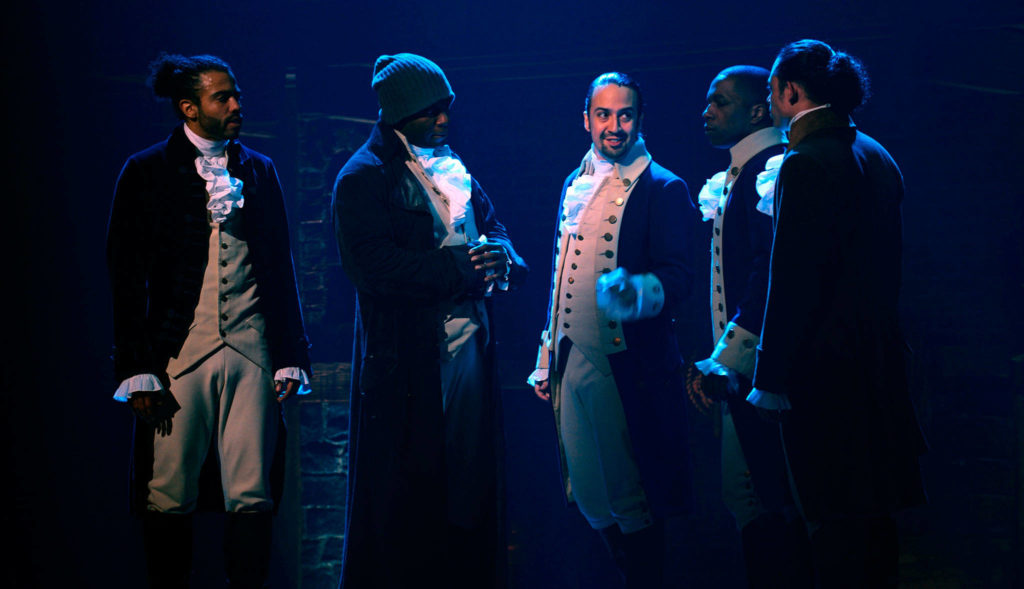

Americans’ rush to watch “Hamilton” on Disney Plus has reignited conversations about the award-winning musical during a time of racial reckoning for the United States. While early criticism of the play in 2016 focused on its glorification of the Founders and the institutions they championed, the focus has now shifted to the show’s erasure of slavery, the politics of Lin Manuel Miranda and the creative team’s “silence” in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, which Miranda apologized for in a video on May 30.

But while it is easy to attack a single 2½-hour musical for not solving racism (much in the way many blame Barack Obama for not solving racism) the show was groundbreaking when it first launched in a moment eerily similar to now. The show debuted at the Public Theater five months after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., amid a national uprising spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement. And now, the film’s premiere on Disney Plus in the context of the protests spurred by the police killing of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd and others reminds us that it is critical — and perhaps even the perfect show — for this moment.

Why? Because “Hamilton” rests on the long tradition of black and brown theater makers using their craft to subvert white America’s dominant narratives. Since the Reconstruction Era, black theater has offered a space to present a counter-perspective of American nationalism; the perspective that centers on black voices and black experiences.

Theater has long been a venue for creating meaning from the nation’s history, and often its most violent eras. In “Hamilton,” Miranda forces his audience to confront the fundamental paradox of the American Revolution: How could a war fought for freedom also uphold slavery? But the script rarely asks that question. Instead, the presence of black men and women embodying the founding generation demands an answer every time they step onstage. Miranda’s project follows a long line of black playwrights and theater makers who have interpreted and reinterpreted America’s wars onstage since the Reconstruction Era.

In the wake of the Civil War, over 180,000 black men who had served in the United States Colored Troops arrived home looking for ways to commemorate their time served and to memorialize the war as a war to end slavery. Many formed veterans’ organizations under the umbrella of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the largest and most politically powerful Union veterans organization in the nation.

The white membership of the GAR almost universally adopted the dominant narrative being peddled to ascribe meaning to the Civil War: It was fought to preserve the Union; the abolition of slavery was merely a fortunate by-product of the nation’s reunification. Like the majority of white Americans, these veterans also believed that Reconstruction was about this reconciliation, not addressing racial inequality. To that end, white GAR members commissioned and wrote dozens of melodramatic plays that pushed the narrative of a war fought to preserve the Union.

Black veterans within GAR, however, balked at this interpretation of the war, and some used theater to challenge it. In 1871, the racially integrated Sedgwick Post of the GAR in Norwich, Conn., commissioned “The Volunteer,” which incorporated a sharp critique of any narrative that dismissed slavery’s role in the war. The play explicitly mentioned the greater sacrifices made by black soldiers because of their inhumane treatment at the hands of Confederate armies.

Another integrated post in Springfield, Mass., performed “The Post of Honor,” which centered on a black soldier heroically fighting to end slavery. Newspapers reported large crowds at these integrated performances, reflecting the desire of black Americans to centralize black stories in public interpretations of the war.

In the wake of Reconstruction and through the turn of the 20th century, when Jim Crow segregation and white supremacist violence were sweeping the nation, multiple black playwrights used the stage to center black families’ experiences with lynching. Koritha Mitchell’s book, “Living With Lynching,” asserted that black communities “used art to sustain conceptions of themselves as modern citizens” in a nation that allowed their execution at the hands of white lynch mobs.

These “lynching dramas” countered the way in which lynch mobs openly celebrated the murders of black Americans. They demanded that attention be paid to the plight of black citizens at a time when governments, especially in the South, had codified segregation and endorsed African Americans’ deaths at the hands of white mobs. While these lynching dramas were not necessarily widely performed, the scripts themselves reflected what Mitchell refers to as “self-conscious efforts” to build community.

Black dreams for citizenship and equality were at the core of the scripts. Lynching plays focused on the experiences of black American families as a direct counter to the dominant narrative found in minstrel shows, vaudeville and mainstream melodrama that portrayed African Americans as violent animals or ignorant buffoons.

Black theater was critical to campaigns for racial equality long before the “modern” civil rights movement of the 1950s. W.E.B. Du Bois’s pageant, “The Star of Ethiopia,” portrayed by a cast of more than 300 black performers, asserted the importance of black Americans to the founding of the United States. The pageant premiered in New York in 1913 as part of the National Emancipation Exposition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

In his 1916 essay, “The Drama Among Black Folk,” Du Bois explained the significance of subverting the dominant historical narrative, claiming that pageants like “The Star of Ethiopia” presented black Americans with “the meaning of their history and their rich emotional life” while simultaneously revealing black Americans “to the white world as a human, feeling thing.” Like the lynching dramas and plays for black veterans, Du Bois’s black theater humanized African Americans in ways that the dominant white narrative never could. It allowed black voices to tell black stories, and insert themselves into the nation’s whitewashed history.

This is why “Hamilton” and the legacies it builds upon are vital to our current moment. Sure, it does not offer a “perfect” history. But it is musical entertainment, not a piece of historical scholarship. Yet, what it does offer is a continued legacy of black and brown theater makers using the stage to deal with the historical contradictions of our nation’s founding. By putting black bodies into the roles of the founding generation, “Hamilton” forces white audiences to sit and consume a reinterpretation of our national mythology, which for too long has only celebrated the work of white men.

As the country debates how history is portrayed through monuments and statues, the reintroduction of “Hamilton” streaming into our living rooms reminds us of how artists of color can use a tradition deeply rooted in the history of African American theater to reshape the dominant national narrative. Black theater has long offered a master class in anti-racist pedagogy and practice, and now, thanks to the “Hamilton” film, hundreds of thousands of Americans are paying attention.

Tyler Sperrazza researches black theater history and civil rights in the postbellum, pre-Harlem era.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.