For nearly a century, Monroe High School athletic teams have been called the Bearcats.

But it wasn’t always that way. Prior to 1924, Monroe Union High’s teams were known as the Panthers.

So, what prompted the name change?

No, there weren’t packs of bearcats roaming the wooded Monroe foothills back in the early 20th century. Bearcats, more formally known as binturongs, are typically found thousands of miles away in the rainforests of Southeast Asia.

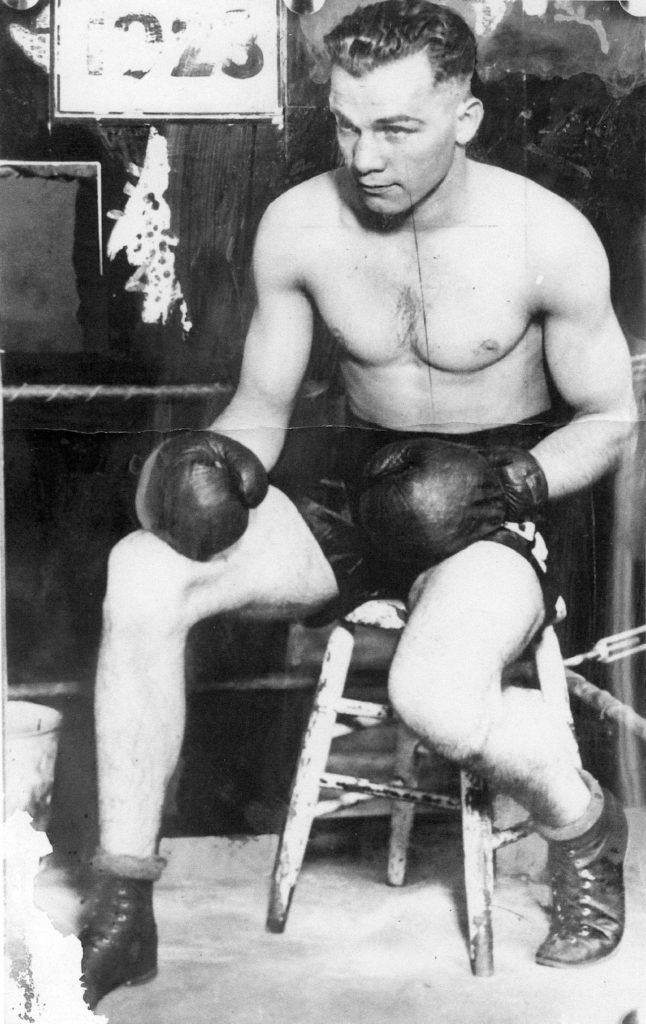

Rather, the inspiration came from famous Monroe boxer Dode “Bearcat” Bercot, a Pacific Coast lightweight champion who captivated fans during the 1920s in his hometown, the greater Seattle-Tacoma area and beyond.

Early in Bercot’s career, a sportswriter from The Herald dubbed him the “Bearcat,” and the nickname stuck. While no records could be found explaining the exact reason for that nickname, the similarity in pronunciation between Bercot and Bearcat likely was a contributing factor.

“I don’t know how they got that name,” Bercot later told the Whidbey Island Record in 1976. “I guess because I was strong like a bear and fast like a cat.”

One year after Bercot’s crowning achievement — a 1923 victory over Hoquiam’s Ted Krache for the Pacific Coast lightweight title — Monroe Union High changed its nickname to the Bearcats in honor of its town’s boxing star.

The late Monroe historian Nellie Robertson, a former lifestyle editor and columnist for the Monroe Monitor newspaper, uncovered the connection between Bercot and the school’s nickname while doing research back in 2001 for one of her books about the town’s history.

With the help of Robertson’s research and newspaper archives, here’s a look back at the man behind the Monroe Bearcats’ name.

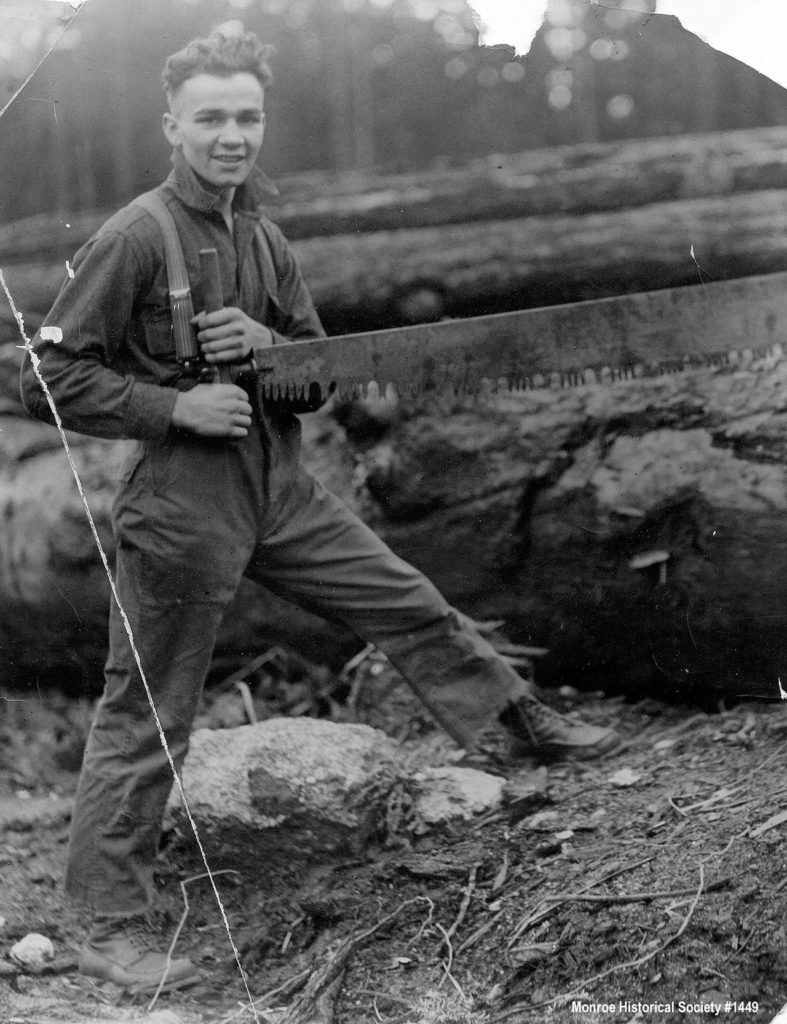

Scaling tall timbers

Born in 1902, Bercot grew up in Snohomish County and later worked in the Monroe area’s logging camps as a high-rigger, which The Herald described as “the most dangerous and strenuous of all occupations.”

This physically demanding job consisted of climbing tall evergreen trees with rope, spiked boots and a saw. Bercot would saw off branches during his ascent and finish by cutting off the very top portion of the tree. This prepared trees to be used as masts in cable logging systems.

“Climbing a tall pine tree in this way — or climbing several trees a day — is a tremendous physical feat, and few men can do it, even if they have the nerve to try,” national sportswriter Robert Edgren wrote. “Being a high-rigger has given Bercot the shoulders of a middleweight… (and) unlimited endurance.”

The exceptional strength and shape he developed as a high-rigger served Bercot particularly well in the boxing ring. He stood just 5-foot-7 and weighed between 135 and 140 pounds, but reportedly had 12-inch biceps and an energy supply that seemingly never ran out.

“There are few boxers in the West any tougher than Bercot,” the Seattle Daily Times wrote during the early part of his career. “It is doubtful if there are any with Bercot’s wonderful stamina and natural physical condition.”

“Bercot is a rugged, persistent fighter and a wearing puncher,” Edgren wrote. “… He wins by outlasting his opponents and wearing them down, increasing the speed of his attack as they grow weary.”

A “meteoric” rise

Seattle boxing promoter Lonnie Austin reportedly discovered Bercot in 1922 while officiating fights in a Monroe lumber camp. After a match between two middleweights who were roughly 15 pounds heavier than Bercot, the Monroe high-rigger approached Austin and said he wanted to face the winner.

Austin reminded Bercot there was a big difference between lightweights and middleweights, but the 19-year-old was persistent.

“I can beat him anyway,” Bercot reportedly said. “Give me a chance.”

Bercot was matched against the winner a few weeks later and needed just three rounds to knock out the larger opponent. Impressed by what he saw, Austin took Bercot under his wing, and the latter began racking up victories and ascending the regional boxing ranks.

“He has more possibilities as a drawing card than any fighter I have ever handled,” Austin told a Seattle newspaper, according to The Herald. “… He is learning fast, and I believe with his fighting instinct and puzzling style, I have a real champion.”

Bercot, somewhat of a rarity back then as a left-handed boxer, quickly became a fan favorite across the Puget Sound area. Fans were enamored with his aggressive fighting style and short, yet powerful punches.

“Bercot is of the sensational type,” the Seattle Daily Times wrote in May of 1923. “His rise in the ring has been meteoric. A few weeks less than a year ago, he fought his first professional fight in Seattle. Since that time, he has had a record of turning away crowds… because of the lack of seating space.”

“Why is Dode Bercot the biggest drawing card in Seattle… show after show?” the Seattle Daily Times wrote later that year. “Because any time he starts, he does some punching. The fans know he can hit and are always looking for the unexpected.”

The championship fight

Just one year after his official boxing debut, Bercot took on Krache in a much-anticipated June 1923 bout for the Pacific Coast lightweight title.

A record crowd of 7,500 fans crammed into Seattle Arena — now the site of McCaw Hall — for the showdown between the two hard-hitters. Monroe’s mayor and approximately 300 fans from the town were in attendance, each wearing a white ribbon badge with the words “Monroe Bearcat.”

“There have been world’s and near world’s champions in Seattle in fights in which their titles were at stake,” the Seattle Daily Times wrote, “yet none of them ever drew through the gates the number of fans who came to see these green, hard-hitting boys.”

Krache, who also worked in the logging industry, entered with a 29-2-2 record and nearly one more year of experience than Bercot. The Hoquiam boxer was widely considered the favorite, and he lived up to that billing for much of the match, using head blows to gain a definite advantage through the first four rounds.

But the tide turned dramatically in the fifth, when Bercot began landing a bevy of “terrific body blows,” according to The Herald. The Seattle Daily Times described that round as a “mauling.”

Bercot continued his onslaught in the sixth and final period, hitting Krache hard and often while ultimately setting up the knockout blow.

“During the first five rounds, Krache held his hands up high to protect his head, so I went for his stomach,” Bercot later told the Whidbey Island Record. “… Finally in the sixth round, it worked the way I figured. Krache brought his hands down and I gave him the knockout punch.”

With the crowd going wild in the match’s closing seconds and Krache back near the ropes, Bercot landed a crashing left hook to his opponent’s diaphragm, followed by a whipping right hook to the Hoquiam favorite’s unprotected jaw. Krache fell to the floor and remained there for the last seven seconds of the fight until the final bell rang.

“The conclusion of the bout was sudden and sensational,” The Herald wrote.

And when it became clear Bercot had triumphed, the Monroe faithful unleashed a spirited celebration.

“Bedlam broke loose as referee Scott raised Dode’s bronzed arm in token of victory,” The Herald wrote. “The Monroe delegation stood on chairs shouting the name of the youthful high-rigger.

“Bercot won because of two things: his fighting heart and his punch,” The Herald added. “The fans packed the Arena to see a rattling good bout. They were given a thriller.”

Monroe’s citizens later held a celebratory banquet for their lightweight champion, and the following year Monroe Union High changed its team name to the Bearcats.

A lasting legacy

Bercot later moved up to the welterweight division and went on to post 81 wins, 16 losses and 39 draws during his nearly decade-long career, according to BoxRec.com. The Monroe southpaw fought in more than 100 main-event bouts and tallied 25 knockouts.

Among the highlights was Bercot’s 4-0-1 record during a successful Southern California tour in 1924. He also had a notable 1928 fight in Oakland, California, that he lost in a controversial 10-round decision.

Bercot and Krache developed one of the more popular rivalries in Pacific Northwest boxing history, fighting five more times after their epic first clash. Bercot finished with a 2-1-3 record against the Hoquiam boxer.

Bercot reportedly lost sight in one eye around 1926 or 1927 after being poked by an opponent’s thumb, but came back to win the fight and continued boxing for several more years.

“The loss of vision in his right eye apparently never hampered his boxing skills,” the Whidbey Island Record later wrote.

Bercot retired from boxing in 1931 and moved with his family to Whidbey Island, where he worked as a state game warden for more than 30 years.

Bercot died in 1988 at the age of 85, but his legacy lives on in Monroe, where countless athletes over the years have competed as Bearcats in front of their hometown fans.

Just like the original “Bearcat” did nearly a century ago.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.