NAGOYA, Japan — With its primary tenant away, the pro stadium here in central Japan was desolate outside. But inside, under its domed roof, there was bustle. Ichiro Suzuki led his team through a workout on the field. Long after most team members had departed, he emerged from an hour in the trainers’ room. His right shoulder had been aching for a few weeks and he was not about to let it impede his performance.

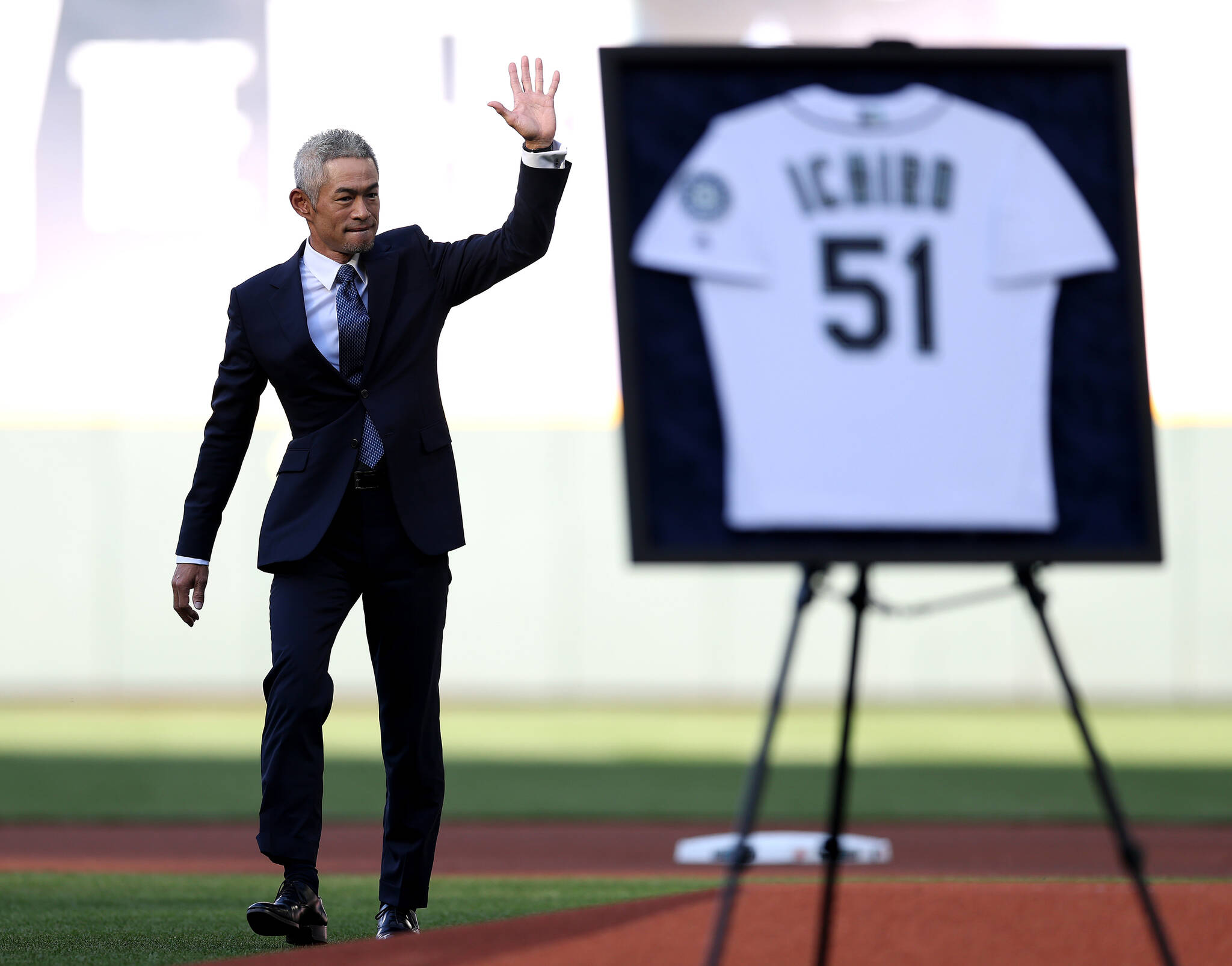

It was late August, and he had just been feted in Cooperstown with induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and again in Seattle, where the Mariners retired his jersey.

Both events celebrated the totality of a brilliant career — one he says he’s not yet finished with.

On this day, Ichiro was readying his shoulder and the rest of his body to pitch the next afternoon in the annual game he now organizes against Japan’s national girls select high school baseball team. It didn’t matter that he would soon turn 52. He approaches this contest with the same focus and intensity that he brought to the 2,653 games he played in the major leagues.

“What I’m doing now is not amusement,” Ichiro said in his native Japanese as he sat beside the massage table. “It’s a serious, competitive undertaking.”

His peers typically choose less active post-retirement endeavors — coaching, managing, media, family life. But Ichiro, as he’s done throughout his career, has gone his own way.

Though the constraints of an official post-retirement role in coaching or managing did not appeal to him, he was intent on remaining active with the game. He felt he could be most effective in communicating with young players leading by example. As in, on the field, side-by-side with them, driven by a firm belief that all the telling in the world pales in comparison to actually doing.

And, by Ichiro’s exacting standards, “doing” requires staying in game shape.

“As long as my body cooperates, I intend to keep doing this,” he said, then adding with a smile, “at least until my gut sticks out and I don’t look good in a uniform anymore.”

Six years of retirement haven’t added an ounce to the 170-pound frame that he maintained over 19 MLB seasons with the Mariners, Yankees and Marlins. Throughout his career, he faithfully used specialized machines to build strength through flexibility and range of motion training. Even now, he uses those machines daily. He still moves just as elegantly.

It helps, whether he’s readying his aching shoulder for a performance that will grow the profile of girls’ high school baseball in Japan, or inspiring professionals such as Bryan Woo and Julio Rodríguez, who have picked up tips on their throwing mechanics just by watching the Mariners’ unofficial coach as the team heads to the postseason. In fact, the impressive sight of the newly minted Hall of Famer Ichiro airing it out in long toss to the budding young star Rodríguez is sure to be one of the memorable scenes at Mariners’ home games this October.

In both of those settings, Ichiro approaches his work with the same devotion.

“Playing baseball captured my heart as a little kid, and I’ve loved the game ever since,” Ichiro said. “Now, I find complete fulfillment in passing that passion on to others who enjoy the game by being on the field with them.”

Many baseball fans have heard of Japan’s boys’ national high school baseball tournament, held at Koshien Stadium every summer for more than 100 years. Five years ago, it began hosting the girls’ national championship, albeit to much sparser crowds.

“The boys’ game is so well endowed,” Ichiro said. “But the girls have to fight for every scrap they can get. I realized that I am in a unique position to give them something really meaningful. I’d be no match for the boys, but I could ramp it up to give the girls a competitive game and really help draw much-needed attention to their sport. I thought, ‘Wow, what a win-win. We’re a perfect match for each other.’”

So each year, he puts together a team featuring friends who have day jobs and other former pros, and seamlessly transitions back to his high school days as a pitcher to play against the girls.

As part of the festivities in Cooperstown, Ichiro was invited to an optional golf outing. He chose instead to spend that time at a neighborhood ballfield. Ahead of his upcoming event in Japan, he felt he couldn’t take time off from running, hitting and throwing. In fellow inductee Billy Wagner and his high-school senior son, Kason, he found willing partners. The work would pay off.

A month later in Nagoya, Ichiro delivered what may have been his best performance in the five years he’s been doing this. He flirted with a no-hitter through 7 2/3 innings and for the fifth straight time, he went the distance. He struck out 14 and walked none on 111 pitches and hit 84 mph on the radar gun. Offensively, he batted lead off, earning a hit and a walk. While his team romped 8-0, the girls hardly felt defeated.

They competed on a professional field at Vantelin Dome, home of NPB’s Chunichi Dragons. They played before 21,233 people, a mind-boggling crowd for a girls’ high school game. They faced a national hero on the mound, backed by a team filled with icons of Japanese baseball recruited by Ichiro: Kazuo Matsui at shortstop, Daisuke Matsuzaka in left field and Hideki Matsui in center field.

The three appeared hobbled and strained at times. Ichiro, by contrast, moved with fluidity. The lone hit came from Ruka Mohri, a high school senior who will forever be able to boast about her big moment.

“I’m going to continue playing baseball in college,” she said, beaming. “And I hope I can keep drawing attention to girls’ baseball with more plays like that one.”

Starting pitcher Sakura Abe, also a senior, left with a memory of her own, getting Matsui to whiff on a two-strike fastball at 72 mph. “I struck him out with my best fastball,” she said, grinning.

Ichiro, who first organized the game in 2021, barely two years into retirement, says the endeavor continues to be rewarding.

“The girls remind me of everything that originally attracted me to baseball,” he said. “They’re respectful of the game and their opponents. They’re appreciative of this opportunity. They take the field with a level of energy and happiness that is contagious, and, most importantly, they really seize this opportunity to improve their play and get better each year.

“If I don’t keep refining my pitching year to year, I’m liable to get knocked out.”

Upon Ichiro’s retirement, the Mariners bestowed him with the fancy but nebulous title of Special Assistant to the Chairman. The role was unknowingly defined by an 18-year-old kid who had just been invited to his first big-league camp.

Julio Rodríguez couldn’t find a throwing partner one day, so he boldly asked Ichiro. Despite a 27-year age difference, Rodríguez has warmed up with the 10-time Gold Glover regularly ever since.

In 2023, that arrangement was more than just a spectacle. It became a learning opportunity for Rodríguez, who struggled with the accuracy of his throws from the outfield. He made a lasting adjustment after observing the way Ichiro transferred the ball from glove to barehand while participating in a throwing drill. It’s precisely why Ichiro insists on staying fit enough to move right along with today’s players.

“Observing something once is far more effective than hearing it one hundred times,” Ichiro said. “Just like that time with Julio, when you see it before your eyes, you’re like, ‘whoa, I get it. This makes sense.’ I can only provide that impact to players I’m with, be it high schoolers or pros, if I make the effort to keep up with them. Seeing makes the message so much more believable.”

For Mariners pitcher Bryan Woo, his “whoa” moment with Ichiro led to a change that he said helped to power his emergence as an ace. From his rookie year in 2023 to the start of the 2024 season, Woo said he threw with a lower arm slot that was both familiar and problematic.

“That was comfortable to me,” Woo said, “but I wasn’t staying healthy.”

He had three stints on the injured list with arm and leg issues. So he studied cellphone video he had taken in the outfield of Ichiro long-tossing with Rodríguez.

“I’m out there every day, watching him long toss, thinking, ‘If he can do it so perfectly in his 50s, why can’t I do it like that in my 20s?’” Woo said. “So I took my cellphone out there to shoot video of him and ended up changing my mechanics because of it.”

Indeed, until leaving his last start with pectoral inflammation, Woo has proven more durable. This season, he was an All-Star and ranks among baseball’s leaders in innings pitched and WHIP. He’s emerged as the ace of the Mariners rotation, leading the staff in categories including wins, earned run average, strikeouts and WHIP.

“By watching the way his whole body was working, I felt the way I was throwing was putting more stress on my elbow; the way he was throwing was using momentum in a better way,” Woo said. “He was using his shoulder and torso in a better way. I tried to borrow little pieces of what I saw. It made me decide to raise my arm up a little bit and I think I’ve stayed healthier because of it.”

When told of the comment, Ichiro flashed a look of content.

“That’s the greatest reward I could ask for,” he said. “If I can impact players at any level to keep finding enjoyment in this game, that’s exactly what motivates me to keep doing this.”

Brad Lefton is a bilingual, freelance journalist based in St. Louis. He covers baseball in Japan and the US and spoke to Ichiro in Japanese for this article.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.