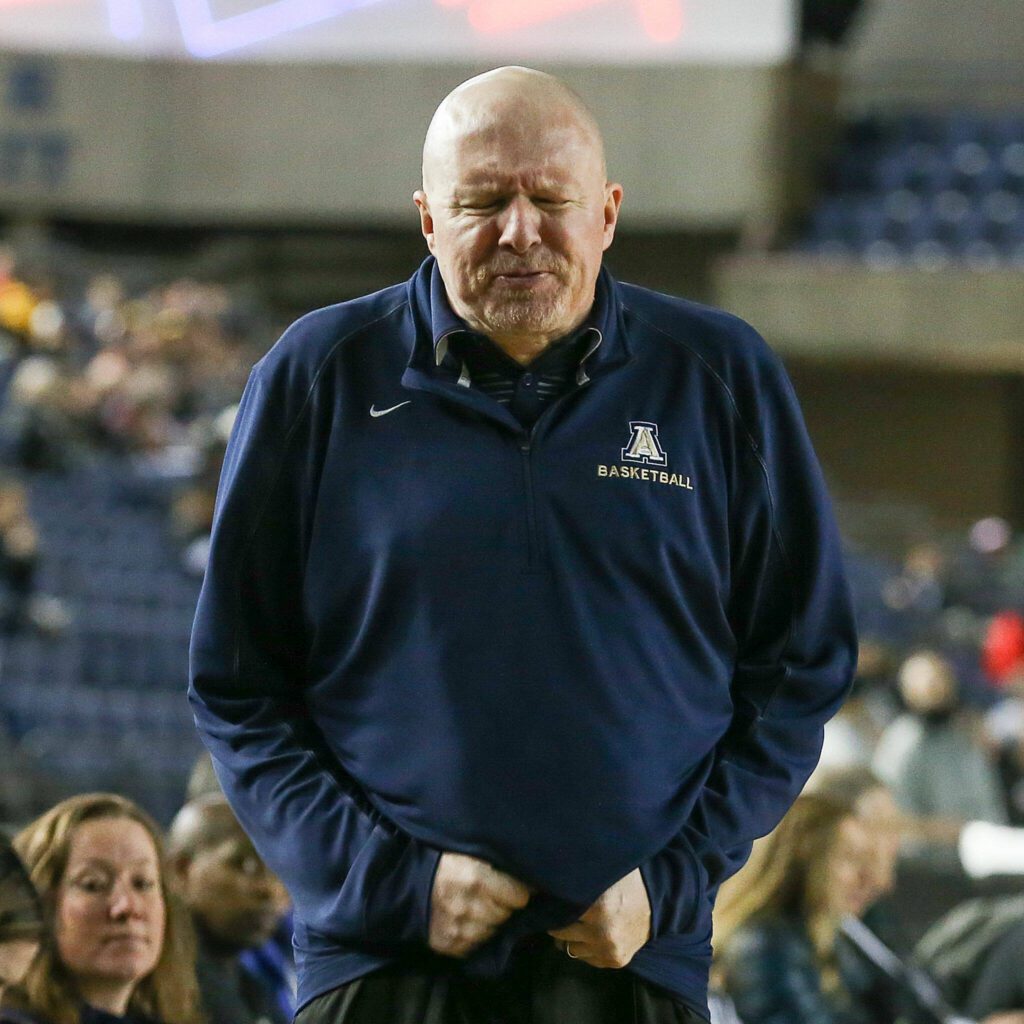

ARLINGTON — For a moment, Arlington High School girls basketball coach Joe Marsh seethed.

At the suggestion of his assistant, the second-year head coach ignored his instinct to foul up by three points in the waning moments of a 2013 Class 4A state semifinal, and watched as Lake Stevens star Brooke Pahukoa hit a 3 to send the game into overtime.

The hearts of all Eagles in the Tacoma Dome sank.

For a moment, he expressed his displeasure. The next, he slid on his knees into the huddle as the team prepared to regroup from the gut punch and recapture the lost momentum as overtime loomed.

“We are NOT losing this game,” he bellowed, looking each player in the eyes as his face reddened. “We are NOT losing this game. We did not come here to lose this game.”

His belief, which had quickly shifted from disbelief, bled into the players in a matter of seconds, and a basketball program that had missed the state tournament for 11 seasons suddenly found its way into the championship game.

“He was amazing in that moment,” said Central Washington University women’s head basketball coach Randi Richardson, who was the Arlington assistant coach that day in 2013. “He knew exactly where his team was at (mentally) in that moment, and he gave them exactly what they needed to come out and be successful as competitors and pull out that win.”

Giving people what they needed was the essence of Marsh. Though he’s in the Washington Girls Basketball Coaches Association Hall of Fame because of nine state appearances in 13 full seasons, it’s times off the court that many people will remember most.

The Arlington community lost a teacher, a father figure and a friend in addition to one of the state’s all-time great high school basketball coaches on Wednesday when Marsh, 57, lost a four-year battle with stage 4 prostate cancer. He died peacefully in his home, surrounded by family and close friends.

He is survived by his wife Sharon O’Brien, daughters Keira and Fiona Marsh, hundreds of basketball players and thousands of students he served as a history teacher at Arlington.

Sean Marsh, who coached alongside his brother for years before filling in as head coach when Joe was hospitalized for a month early in the 2024-25 season, was struck by his brother’s legacy at — of all places — the dump. He pulled up to the booth to pay, and the attendant said, “You’re Joe Marsh’s brother, aren’t you?”

“He was probably about 27, and he said, ‘He was my favorite teacher of all time,’” Sean Marsh said. “And the girl in the booth across from me said, ‘Are you talking about Joe Marsh? He was my favorite teacher of all time.’”

“A lot of people tell me this. I go into grocery stores, a lot of places … that’s just the kind of impact he had. It wasn’t just as a basketball coach. It was as a teacher, a mentor, a father, a community leader. He just really did it all.”

Diagnosed in 2021, the cancer continued to grow. In 2022, he was told he had 6-9 months to live. Much like the belief he instilled in his players, Joe refused to give up. He beat the odds and continued to coach until he was rendered unable to walk in January due to a spinal tumor that led to surgery and a 33-day hospital stay. He fought and coached basketball for longer than could have been expected.

“He gave every ounce of his life to his family and to his program that he built, and that he was so proud of,” Sean Marsh said.

That stubbornness required to never give up comes in part from Joe’s East Coast roots. Joe Marsh, the oldest of six siblings — five of whom have coached basketball — grew up in South Jersey just outside of Philadelphia. The family of eight moved to Arlington to run a business. As a 16-year-old senior who had skipped a grade, Joe lost his father to a heart attack. He played on the University of Washington junior varsity basketball team in the mid-1980s before the family moved back to New Jersey. Joe Marsh, though, returned west because he missed O’Brien. The couple eventually married, and Joe began teaching at Arlington in 2004.

He was an assistant with the Arlington boys basketball program before another coaching position piqued his interest in 2011: Arlington High School girls head basketball coach. He thought about his daughter, Keira, who was a youth basketball player, and considered the possibility of coaching her in the upcoming years.

It turned out to be a great move for many people.

He took over a program that had eight total state appearances in its history. Through the end of the 2023-24 season, Marsh went 238-76 in 13 seasons, winning eight Wesco titles. He was named Wesco Coach of the Year five times and was The Herald’s All-Area Coach of the Year twice.

His teams made nine state appearances. Though the state title he desired eluded him, Arlington went to the championship game twice and the semifinals five times — including three straight trips from 2021-2023. While he fought through the effects of chemotherapy and cancer’s advances, Arlington finished fourth in state in March of 2024 to culminate his last full season.

Joe was known for winning, and his fiery side led to some technical fouls over the years. He worked the officials and fought for his players. They, in turn, fought for him. The game intensity quickly dissipated, win or lose, at the final buzzer. The referees and rival coaches immediately became his friends. His demeanor after games was the same, win or lose, when he talked with reporters, as well as coaches and players from both teams after games.

He built a youth feeder program to help grow girls basketball in Arlington. He became an advocate for Wesco basketball, often helping the very coaches who would try to beat him.

Defeating him, though, was not easy. He won 137 league games while losing just 28 — a winning clip of 83 percent. He was known for coaching his players’ hearts and mentality as much as teaching offense and defense, which led to the Eagles playing hard until the end.

“It was miserable,” quipped Glacier Peak coach Brian Hill when asked what it was like to coach against Marsh. “His teams were some of the best defensive teams throughout the league over his time at Arlington. You knew what he was going to do, it was just tough to get through it. He was going to bring hard pressure, and his kids really bought into what was going on and made things miserable.

“They were very disciplined, and they were definitely in shape. They would go the whole game and just keep putting it on you.”

After the evening of intensity, Joe quickly put games behind him and gave his attention to a family he loved dearly.

His daughter, Keira, who was an important part of two semifinal teams, now plays for Richardson at CWU. Though coaching one’s own child can be challenging, it was a great time for both of them.

“We obviously had our moments when I’d give him some daughter attitude,” Keira Marsh said. “… But it’s hard to remember any bad experiences, because I loved it so much. He made me a better player, and I think we worked pretty well together. I know with most people, it’s not that experience.”

That’s likely because the whole team was like a group of daughters to Marsh. While he demanded much of them, he built family relationships with his players that continued beyond high school. While he expected the physical fitness required to play his relentless pressure defense, his players loved him for his softer side.

On most Saturdays during the season, Marsh wasn’t running fast-paced practices to work out the kinks from Friday night’s game. He was usually handing out donuts and chocolate milk. The players sat in a circle, sometimes talking about basketball, sometimes not. Sometimes they joked around, and on other Saturdays, they talked about tough life situations that brought tears.

For Gracie Phelps (Gracie Castaneda during high school), her coach provided stability to help her overcome a difficult upbringing.

“He was probably one of the top three most influential people in my life,” said Phelps, who has followed her coach’s footsteps to become a high school teacher and coach. “I grew up in a pretty hard home, hard childhood, and I didn’t really have a father figure. Marsh became that for me in high school.

“There were times when he was scary, for sure, but it was all out of love — and we knew that. There were so many things that Marsh did for us on and off the court.”

Phelps also recognizes how difficult it is for a person to give so much as a teacher during the day and then carry that energy to practices and games in the evening.

That spark came from a passion for the game and helping the girls grow as players and people.

“It’s hard to come by a coach that can also be one of your best friends,” said Jenna Villa, The Herald’s 2022-23 All-Area Player of the Year, who will be a junior on the Oregon State University women’s team next season. “He was someone I could go to for anything.”

Villa met her former coach for coffee from time to time and learned that Marsh kept in contact with countless former players to chat about basketball and life. People knew he was proud of them, though he wasn’t afraid to give them advice.

Richardson benefited from Joe’s guidance as much as anyone.

An Arlington grad, Richardson returned home in 2011 after her senior women’s basketball season at Wyoming, feeling burned out about hoops and thinking her “relationship with basketball was done.”

Joe heard she was back in town and gave her a call. She started turning down an offer to get involved with coaching at Arlington, but Joe wanted to hear it in person.

In his room at the high school, he made it clear that he wanted her to be the junior varsity head coach. Richardson felt she would never have interest in being the head coach of anything.

“That’s nonsense,” he told her.

Now a college head coach, Richardson is thankful for Joe’s stubbornness.

“I said there was no way I was doing that,” Richardson said. “I remember him saying, ‘You’re so ready. You’re going to be great. That’s nonsense.’”

Richardson will miss her mentor’s guidance. Joe helped her identify players who would be a good fit for her team at Central and talked her through the tough moments of a coaching career.

Like most people, though, Richardson will miss her friend.

“He loves his players, and he’s passionate about the game of basketball, and about the growth of his teams,” Richardson said. “But not an ounce of who he is as a coach is self-serving, or about him. It’s all about his players, his program and the love he has for the game. He’s just such a good guy — a respected competitor.

“A great friend.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.