EVERETT — It was a high school football powerhouse so dominant that other teams in Washington didn’t want to play it.

No, this isn’t the story of the 2016 Archbishop Murphy High School football team. It’s one of a squad that earned itself a place in prep football lore with its mastery of the gridiron 100 years ago.

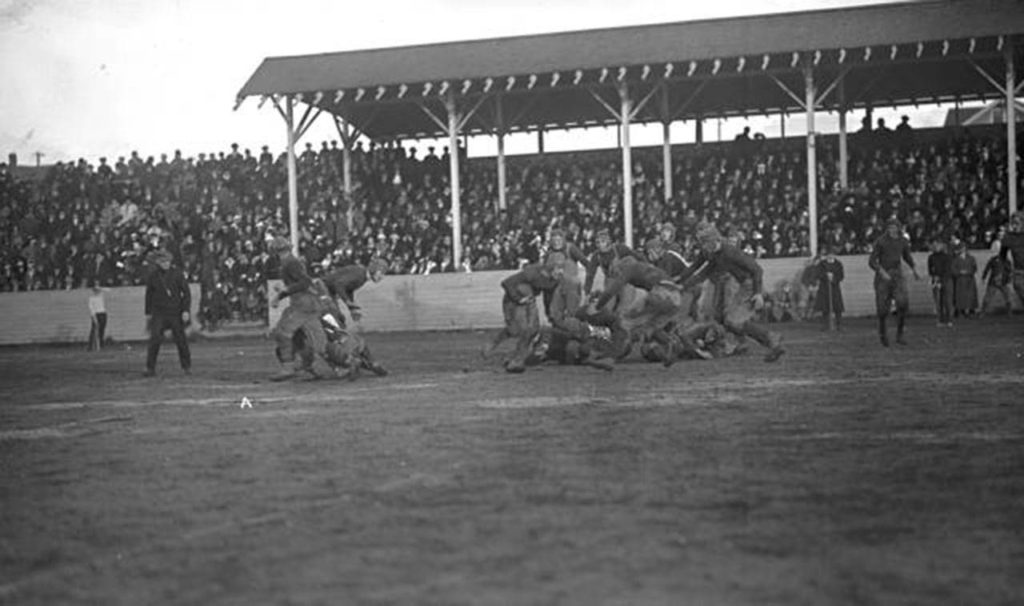

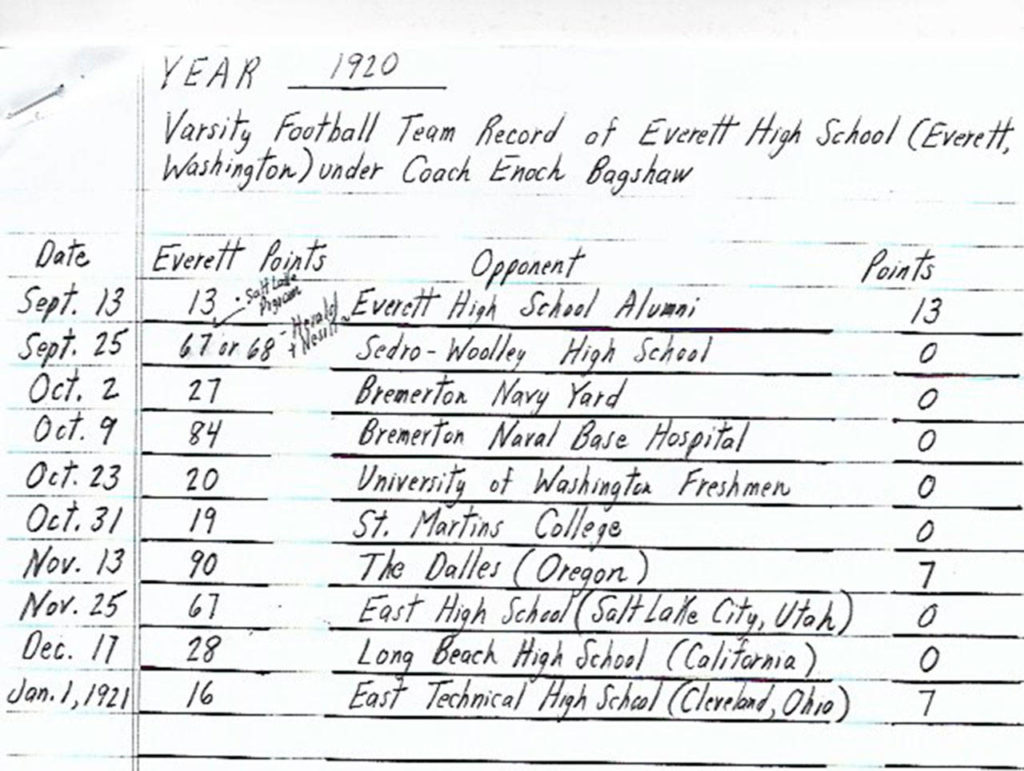

On Jan. 1, 1921, Everett High School laid claim to a national championship with a 16-7 victory over East Technical High School of Cleveland at Athletic Field in Everett, now the site of Bagshaw Field at North Middle School.

Everett’s victory was the result of a gritty style of football that would be hardly recognizable today. With quarterback Glenn Carlson, fullback Lester Sherman and running backs George Wilson and Carl Michel leading the offense, Everett churned out 365 rushing yards on a whopping 76 carries, largely on runs between the tackles. Just eight passes were thrown.

“There was nothing fluky about this victory,” a Jan. 3, 1921, article in The Everett Daily Herald said. “It was hard earned over a high class gridiron machine that played with marked skill and headiness, over a team that was ready on the instant to convert the slightest advantage into a scoring opportunity. Everett won because the whole team was on its toes from start to finish.”

There certainly wasn’t anything fluky about Everett’s national championship. The team was battle tested.

Led by legendary coach Enoch “Baggy” Bagshaw, Everett entered the national title contest with an 8-0-1 record after playing a schedule that included teams with players much older than its own. Everett beat a pair of teams from the military, Saint Martin’s College and the University of Washington Freshmen.

The squad had accumulated so many blowout wins in years past that it struggled to find high school opponents in the state that were willing to play. Sedro-Woolley was the only Washington high school that played Everett, a 68-0 triumph for the eventual national champions.

The 1920 schedule also included top high schools from Oregon, California and Utah. The Bagshaw-led squad allowed just seven combined points in those three games while racking up 185 of its own on offense.

The team was more than just a winner to the city of Everett, though. It was a ray of light in some dark times for the mill town.

The city’s wealthiest residents and its working class were at odds during these years. Mill workers were fighting for higher wages and better working conditions. In 1916, the infamous “Everett Massacre” occurred, a day when seven people were killed in a shootout between members of the Industrial Workers of the World union and local authorities. Tensions remained four years later.

The fighting between citizens stopped when Everett football became the topic of conversation.

As cited in Lawrence E. Donnell’s book, “Soaring Seagulls: Highlights of Everett High School Sports 1892-2001,” newspaper columnist Rosie Weborg years later wrote, “It did not matter whether it was a banker or laborer, merchant or professional man. They all met on common ground when Baggy and football were under discussion. The rich man would discuss it by the hour with his poorest neighbor and from this sprang an era of civic solidity that may never come again.”

Bagshaw was born in Wales in 1884. His family moved to Seattle in 1892. He went to Seattle High School before going on to star on the University of Washington football team, earning five letters and serving as a team captain. He played quarterback, running back and end.

Bagshaw was just 25 years old and unproven as a coach when Everett hired him in 1909.

His squad went 5-3 in his first season, and it appeared he wouldn’t return for a second. The school didn’t renew his one-year coaching contract. Everett hired Ralph Cole to be its coach the next season.

Cole never coached a game at Everett, though. He ruptured a vein in his leg before the season and required surgery that would keep him off the sidelines. Everett then hired Pete Tegtmeier to be coach, but his work schedule prevented him from holding practices before 5 p.m. The school then brought Bagshaw back to coach the team.

The 1910 team finished with a 5-4 record, but Bagshaw’s tough practices and propensity to schedule challenging opponents was enough to convince Everett to keep Bagshaw on for the 1911 season.

That proved to be a fruitful decision.

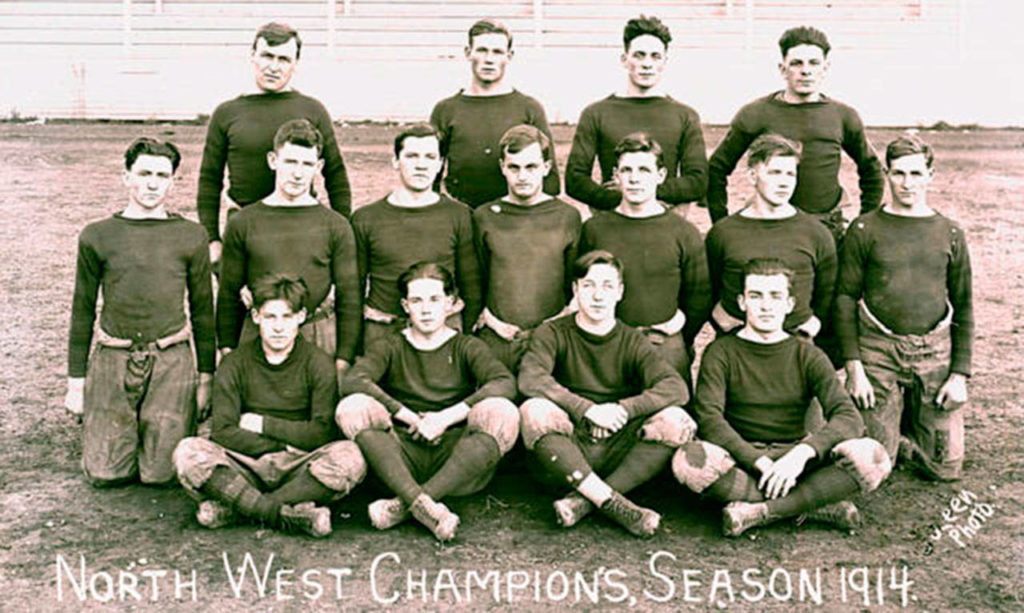

Bagshaw’s squad was nearly unstoppable in his third year. Everett won its first seven games by a combined score of 244-0 before allowing points in a 12-6 win over Lincoln High School of Seattle. A 0-0 tie against Tacoma High School the following week kept Everett from a perfect season, but a pair of blowout wins following the tie left little doubt who the best team in the state was. The Washington State Athletics Association awarded Bagshaw and his players a state title, the first of many accolades Everett received during Bagshaw’s tenure.

“A football dynasty had begun and a ‘School of Champions’ identity had been born,” O’Donnell wrote in his book.

From 1912 to 1917, Bagshaw’s teams went 46-8-3, including 38-1-3 against other high schools. Five of the eight losses in that span came against college teams and two against teams composed of Everett alumni.

In the most lopsided game over that stretch, Everett beat a team with players from two Bellingham high schools 174-0 in 1913.

“The ball never found a resting place on Everett territory,” an Oct. 13, 1913, article in The Everett Daily Herald said of the game. “Everett got a touchdown in the first minute of play and repeated this as rapidly and as certainly as the pill was put back in play. The ball was passed around among the team members and each practiced sprinting. When one player got tired of this practice or ran out of wind, some other player took the leather egg and did likewise.”

After the 1913 season, the cities of Seattle, Tacoma and Spokane banned intercity competition for their teams. Many of the Everett faithful believed it was because the city schools didn’t want to play Bagshaw’s team.

In 1918, Bagshaw left to serve in the United States Army during World War I. He returned in 1919 with his best squad yet.

The Everett boys put together another unbeaten season, which included a 125-7 thumping of Lincoln High School of Portland for the Northwest Championship. The victory put Everett in a national championship game with Scott High School of Toledo, Ohio, on Jan. 1, 1920. The game ended in a 7-7 tie.

Exactly one year later, the team won its national title. It was Bagshaw’s last game in Everett. He became the head coach of the University of Washington and led the Huskies to their first-ever Rose Bowl appearance in 1923.

Remember the Seagulls

The Everett Public Library’s Northwest Room is holding a free online program to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of Everett’s national championship victory Saturday at 5 p.m. on Crowdcast. Everett School District teacher and local historian Steve Bertrand will share photos and stories from the season. More information on the event can be found at epls.org.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.