MUKILTEO — When the new Boeing 777X taxied onto Paine Field’s main runway last month, Gina Morken and Carmen Evans left their desks to watch the “neighbor” fly for the first time.

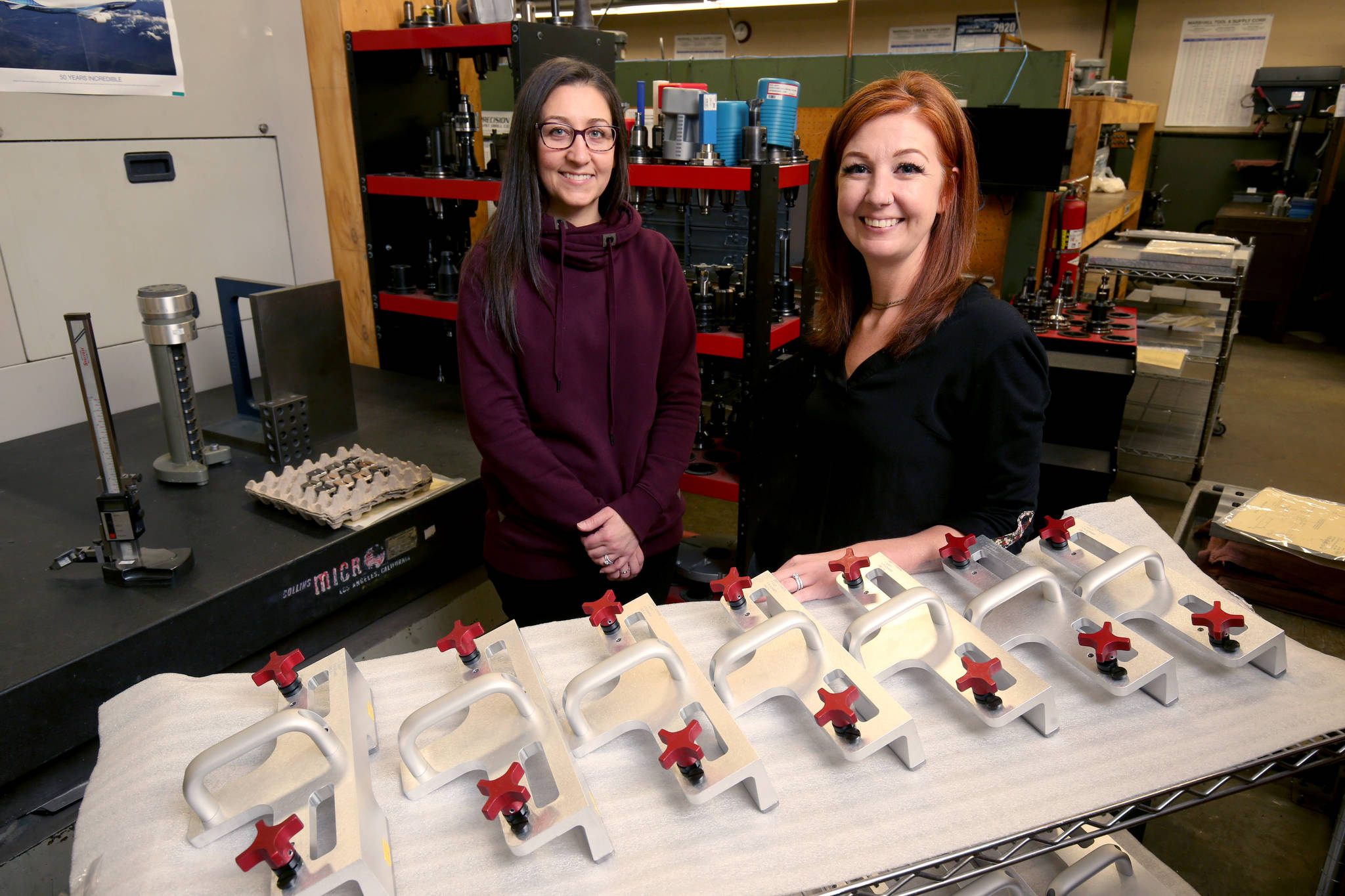

Their Mukilteo machine shop overlooks Boeing’s Everett assembly plant, and the two sisters can lay claim to helping Boeing’s newest plane catch air.

Their company, New Tech Industries, spent a year making the tool that’s used to drill hinge holes for the 777X’s 11-foot folding wingtips.

While the 84-inch boring bar was Boeing’s design — the jetmaker provided the blueprints — it was up to New Tech to bring it to life and perfect it.

“There were a lot of things we had to figure out,” Morken said. Heat-treating a bar of that length, and then finding a nearby firm that could chrome the device, were among the challenges.

The year-long undertaking, Morken said, “was one of the coolest projects we’ve ever done.”

About 90% of their business is generated by Boeing.

“We build any kind of tool, such as special wrenches and drill jigs, that Boeing uses to build planes,” Evans explained.

Snohomish County is home to about 200 aerospace suppliers, including a handful operated by women. The maiden flight of the 777X was a bright spot for New Tech Industries and other suppliers during a year that, so far, has been marked by uncertainty.

These days many suppliers face hardships, including workforce cuts and reduced hours — the result of Boeing’s decision earlier this year to temporarily halt production of the Renton-built 737 Max. The plane has been grounded since March 2019 after two fatal crashes killed 346 people. Chicago-based Boeing has said it plans to resume production before the plane is re-certified, which it expects by mid-year.

“Everyone is having the same problems. We’re not alone,” said Morken, who treasures a close work relationship with her sister that allows them to make business decisions quickly.

A pause — without layoffs

The narrow-body, single-aisle 737 accounts for about 70% of Boeing’s commercial aircraft production and generates significant revenue for outside suppliers, including New Tech, which is considered one of Boeing’s top suppliers.

“We’re a ‘Tier One’ shop. That’s how critical we are in the supply chain,” Morken said.

With the 737 Max assembly line shuttered, New Tech has placed a dozen of its 38 employees on “standby,” a temporary unemployment status offered by the state.

It’s different than a layoff, Morken said. Workers receive full unemployment benefits but aren’t required to search for a new job. In addition, New Tech pays for health benefits.

“It’s an expense,” Morken said. “But it’s important to us … we want them to come back.”

SharedWork, the state program that manages the standby process, limits the employment pause to eight weeks. New Tech is approaching the cutoff date. After that, it becomes a layoff, Morken said.

The shop also has been forced to cut its work week to 24 hours. For now, workers collect partial jobless benefits intended to remedy short-term economic setbacks.

“We’re only open Monday, Wednesday and Friday,” Morken said.

Boeing has said that it plans to shore up its supply chain with cash and orders.

”We’ve been in close contact with our procurement agent at Boeing,” Morken said. “We’ve let them know we’re hurting.”

Sweeping floors

Morken and Evans took over the business when their father and founder, Tom Bigelow, died in 2008. Their mother, New Tech’s president, is a silent partner.

The two sisters grew up around the business, sweeping the floors on Saturdays and then tinkering in a makeshift shop Bigelow built for his daughters in the family garage.

He brought home odd jobs for them to finish and expected them to partake in his work victories — like the family outing he mandated after he purchased his first Electronic Discharge Machine, a precision metal-cutter.

“I was in eighth grade and we all had to go,” Morken laughed. “It was like, ‘OK, dad.’”

“The smell of a machine shop? That’s our dad’s cologne,” Morken said.

At Snohomish High School, Morken enrolled in metal shop and welding classes and then caught flak from a high school counselor when she tried to enroll a second time.

“He said I should probably try doing something else,” she recalled. That was 1997.

After graduating from high school in 1999, Morken got a job in the shop’s de-burring room, “the crappiest job in the world. I knew my dad wasn’t going to hand me some posh job right off the bat,” she said.

Loud, gritty, dirty, it involved sanding, grinding and sandblasting metal parts. “I remember thinking, ‘I don’t know if I can do this my whole life,’” she recalled.

She stuck to it for a year and a half, then graduated to the more satisfying assembly room. “You get to see the end product that the shop has been making,” she said.

Evans joined the company a few years later after working as a veterinary assistant. Evans volunteered to answer phones for two weeks while the company looked for front-office help.

“They never even looked for a replacement. They didn’t even run an ad!” Evans laughed, looking at her sister.

“We were trying to bring her back to the dark side,” Morken joked.

‘Classwork wasn’t my thing’

New Tech welcomes high school and college level apprentices through the state’s Aerospace Apprentice Joint Committee program.

Morken identifies with many of those young apprentices. “Classwork wasn’t my thing. I liked making things. I didn’t get the best grades,” she explained. “There’s a lot of guys here that feel the same — classwork isn’t for them — but that doesn’t mean they’re not smart or talented,” she said.

Meanwhile, both sisters worry the volatility around Boeing and the 737 Max might discourage young people from choosing an aerospace career.

When Morken and Evans had to announce cutbacks at the shop, Morken dabbed back tears. “That’s the first time I’ve ever cried in front of the shop,” she said.

“We have a lot of people here that have worked here for 25 years,” Evans said.

Bud Everett, who runs the grinding department, has worked at the shop for 28 years. His son, Brandon Everett, has been in assembly for 15 years.

Ryan Pipkin, who started with New Tech in 2003 and now works in quality control, wishes things would get back to normal. “I’d like to return to five days a week,” Pipkin said.

For now, the sisters can only watch and wait.

“The goal is to bring everyone back to work this spring,” Morken said. “That is the hope. But you don’t really know. I cringe every time I read the news. We can only take it day by day.”

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097; Twitter: JanicePods

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.