The Boeing Co. is turning 100 on July 15. Throughout the year, The Daily Herald is covering the people, airplanes and moments that define The Boeing Century. More about this series

Boeing engineers are constantly generating new product ideas. Some are better than others. Some are bold and push the boundaries of what’s possible. Others seem inspired by science fiction. And some sound silly today.

The aerospace giant’s innovations are ideas that panned out. Here are some that did not.

Model 326

The clipper of tomorrow never arrived.

In 1937, Pan American Airways wanted an amphibian capable of safely flying nonstop from America to Europe. Boeing proposed its double-decker Model 326, a six-engine clipper with room for 100 passengers. The enormous plane was to be an ocean liner in the sky, complete with luxurious lounges for passengers to relax in during the long trip across the Atlantic Ocean. The Model 326 would have been the first pressurized airliner. However, Pan Am did not pick any of the four competing designs. And the first pressurized airliner became the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, which entered service in 1939.

As late as 1942, Flight magazine referred to the Model 326 as the “clipper of tomorrow.”

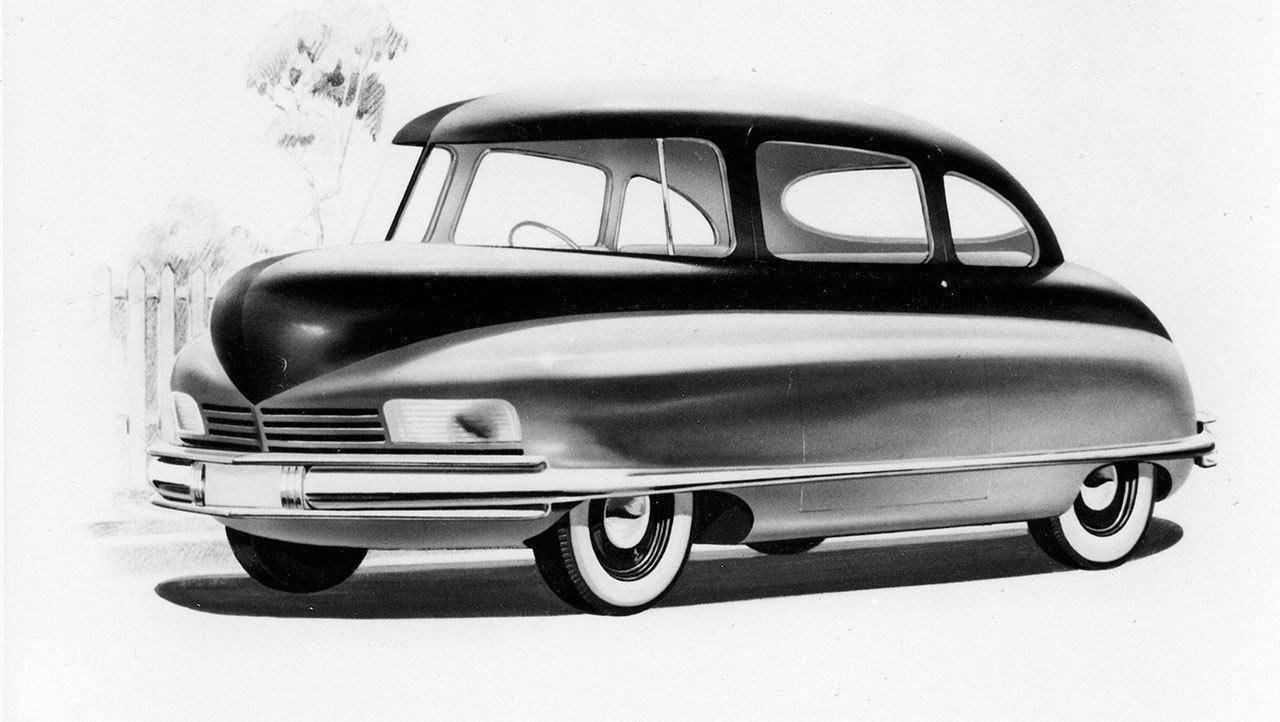

PA-3

It looked like a cartoon car, but it was a very real idea — and it almost became reality.

During World War II, Boeing and its competitors had focused on making warplanes. With the war winding down and soldiers returning to civilian life, Boeing looked for products to sell to vets in peacetime. It designed a car, a van, modular housing units and even kitchen appliances. In the end, the company stuck with what it knew — airplanes.

While the U.S. military canceled most orders for warplanes after 1945, Boeing kept busier than most of its competitors thanks to continued demand for the B-29 and its new, jet-powered B-47 Stratojet bomber, which first flew Dec. 17, 1947.

X-20 Dyna-Soar

It was a reusable space plane that no one ever used.

In the late 1950s, the U.S. Air Force wanted to fly to the stars. Boeing’s design, the X-20 Dyna-Soar, beat out eight competitors. It was designed to be flown both as an airplane in Earth’s atmosphere and as a spacecraft — just like the space shuttle a quarter-century later.

In 1960, the Air Force picked seven astronauts, including Neil Armstrong, for the X-20 program. The first space flight was tentatively scheduled for early 1965.

The Dyna-Soar never made it past the mock-up stage. Congress opted to shift the X-20’s budget to the Gemini program.

The Air Force had already spent $410 million — about $3.2 billion today — on mock-ups before the X-20 was canceled. Research for the program later influenced the development of the space shuttle.

2707

In the mid-1960s, the future of air travel was clearly supersonic. At least, that was what many folks thought. Boeing and Lockheed vied for a federal contract to develop a supersonic transport (SST).

“At stake in the battle are billions of dollars, thousands of jobs, American prestige, the U.S. balance of payments and the futures of the two aircraft builders,” the Associated Press reported in 1966.

The Boeing 2707 won the contract. It was the company’s marquee program and attracted many of its best and brightest engineers.

“Our SST colleagues were clearly the haves to our have-nots,” Boeing engineer Joe Sutter wrote in his book, “747: Creating the World’s First Jumbo Jet and Other Adventures from a Life in Aviation.”

Boeing’s other development programs at the time — the 737 and 747 — had to fight for whatever resources the 2707 did not command.

The Boeing 2707 would have held about 275 passengers, making it roughly twice as big as the Concorde. The program had more orders than the Concorde, too — 122 from 26 customers.

However, interest waned due to environmental concerns and rising fuel prices. Boeing canceled the program after Congress pulled its support in 1971.

Double-deck 747

The Boeing 747 began as a full double-deck airplane, essentially two 707 fuselages stacked on top of each other. That design would not allow it to carry much cargo, and the plane would have been hard to evacuate in an emergency. So Boeing switched to a single-deck design. To do so, it had to get launch customer Pan American Airways on board.

Boeing’s Milt Heinemann flew to New York and convinced Pan Am’s leadership to consider one wide deck. Pan Am agreed to consider both designs. Boeing made mock-ups of each, which the airline’s execs inspected in Renton.

The trip convinced Pan Am president Juan Trippe that a single, spacious deck was the better design.

767-X

By the 1980s, European airplane maker Airbus had made significant inroads into the twin-aisle jetliner market. Boeing engineers searched for a response.

“The 767 was starting to lose some campaigns against the A330, so we knew we needed to do something,” Boeing Vice President Lars Andersen told The Daily Herald in Everett in 2015. In the ’80s, he was part of the 767 program. Boeing’s first responses were bigger versions of the 767, including one with a partial second deck at the rear of the plane. The awkward-looking plane was nicknamed the “Hunchback of Mukilteo.”

Airline executives weren’t interested in the Hunchback, though. So Boeing opted for an all-new airplane, which became the 777.

777-100

When the 777 first flew in 1995, it was a 777-200. So why didn’t Boeing make a 777-100?

That designation was used for a conceptual design from the late 1970s. It was a large tri-jet airliner, but Boeing shelved the project in favor of two twin-jet airplanes: the single-aisle 757 and the twin-aisle 767.

Even though the earlier tri-jet never flew, Boeing launched the 777 family with the 777-200, rather than a -100 variant.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.