This is one of several stories about essential workers during the COVID-19 outbreak. They might not be true first responders, but we couldn’t live without them.

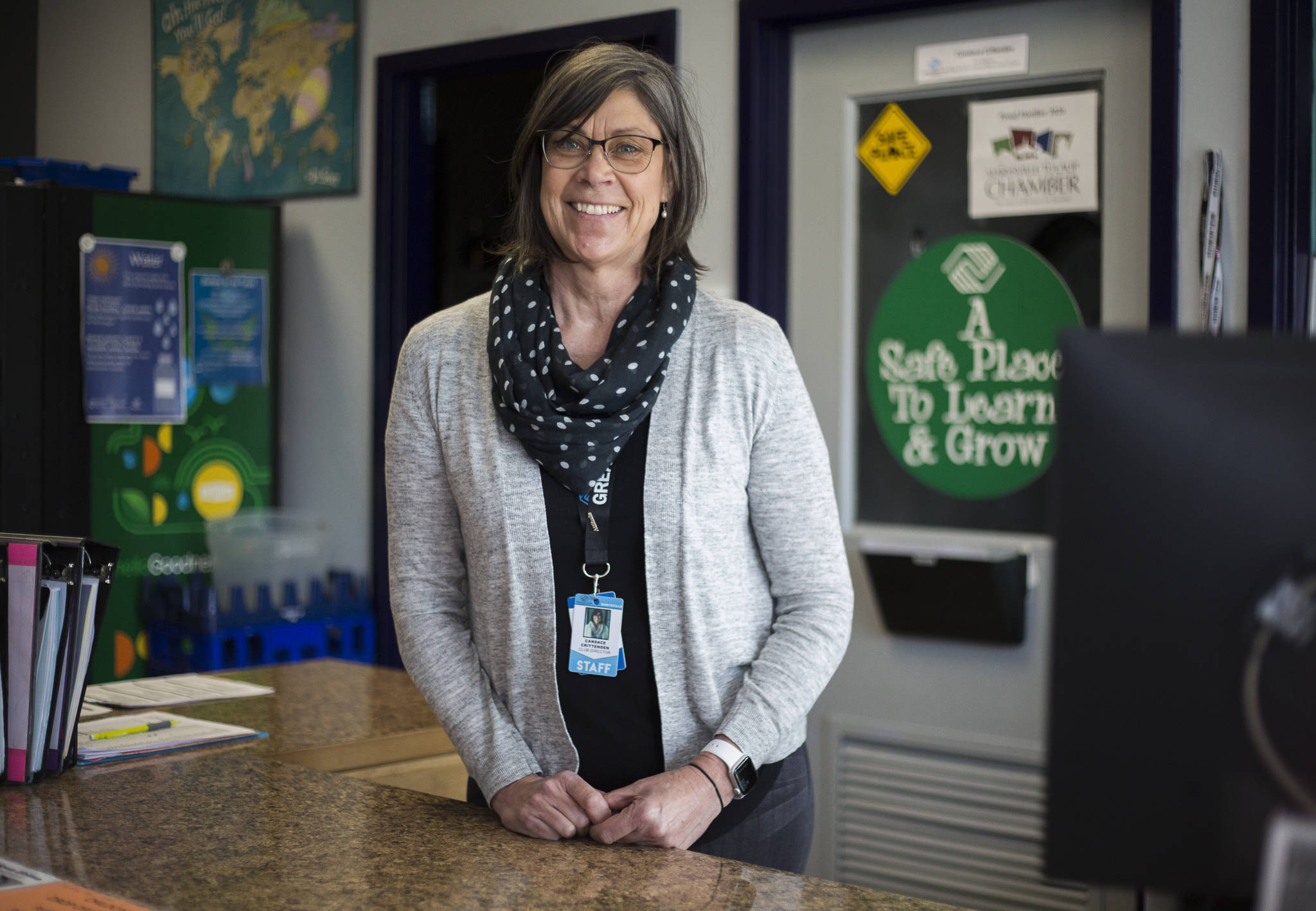

MARYSVILLE — The other day Candace Crittenden ducked into her office at the Marysville Boys & Girls Club and closed the door.

“I had reached a breaking point. I was in tears,” said Crittenden, the club’s director. “I started to feel that we weren’t as essential as other people.”

Crittenden’s “kid biz” career goes back decades to when she studied special education in college and unlocked a soft spot for children.

“Some things choose you,” she proffered.

In March, the YMCA and the Snohomish County Boys & Girls Club announced they would provide free child care to health care workers and first responders.

The offer brought a new routine and new kids to the club, Crittenden said. Many of their parents are on the front lines, battling the COVID-19 outbreak, she said.

“You hear about doctors, first responders showing up to work every day, putting themselves on the line, risking their lives. The majority of our parents are in some sort of health care,” Crittenden said.

When you compare yourself to them, “It’s hard to feel as important,” she said of the inner voice that forced the retreat to her office.

In another time, in other circumstances, Crittenden would have “put on her big girl pants” and cut short the tears.

Instead, she let herself weep a little. And then it dawned on her: “We are here, too. We take care of valuable little kids that allow them to do what they do.”

When she emerged from her office, she had a message for the staff. “You come to work every day. You put yourselves at risk as well. You’re doing an amazing job.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has turned everyone’s life — parents, kids, her staff —upside-down.

“Nobody is unaffected by this,” she said.

Crittenden has two grown daughters and three grandchildren whom she can’t visit right now. Hard for someone who describes herself as a “natural hugger.”

“I’ve switched over to a lot of virtual high fives and air hugs,” she said.

As club director, Crittenden has had to lay off staff and juggle schedules.

Staff put tape on the floor to mark social-distancing parameters. Children have been given hula hoops to wear around their waists as reminders to sit six feet apart.

It’s not easy.

Each morning about 20 kids get dropped off to spend the day at the Marysville club.

Most of the kids are elementary-school age, and with schools closed they spend all day at the club.

That means no more middle-of-the day respite for staff.

“It’s like summer camp all of a sudden hit us,” Crittenden said.

“Some kids want to come here and play video games all day. I have to tell them, ‘I know you don’t want to be here, but that’s something you need to talk to your parents about.’”

The day begins with breakfast, maybe some free time in the gym, she said.

A designated homework hour now stretches into a second hour. “If the kids have Chromebooks (laptops) from school, we coordinate with their teacher.”

When the online school day ends, the kids can go into the computer lab. “But we limit the games they play,” Crittenden said. “They have to do some research. We might give them 10 facts to look up.”

Some kids haven’t missed a step, she said. “They’ve adapted pretty well.”

A few struggle. It’s not an easy conversation, but sometimes “we have to call their parents and tell them, ‘I don’t think this child can be there all day because it’s too much out-of-the-ordinary for them,’” she said.

A big part of getting the message across to the kids is “letting them know this is hard for all of us — I know you miss school and your teacher and friends,” she tells them.

A few weeks ago, all the kids got journals. Each day they’re given time to write. “They can express how things are for them — how hard it is,” she said. She paused, and added, “How hard it is for us, too.”

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097; Twitter: JanicePods

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.