All Funko toys are born from pop culture.

The Everett-based company, which reported $686 million in net sales in 2018, gets its inspiration from the likes of Batman and Cinderella, Sailor Moon and Spider-Man.

“If something relevant happens on screen, that’s where it starts,” said Ben Butcher, vice president of creative at Funko.

From the drawing board to the sales floor, it takes months to create a Funko collectible. The creative work happens on the fourth floor of company headquarters on Wetmore Avenue.

There, some 85 artists work out every minute detail of each toy, from idea, to 2-D concept, to 3-D digital model, to production overseas, and finally on store shelves.

Funko allowed us extensive access to its creative process to help tell the story of how the figures, which have spawned an army of collectors, are made.

But first, a little history is in order. The company, like so many, started in a garage. Mike Becker founded Funko in 1998 in Snohomish, with early products such as bobbleheads and coin banks based on cereal advertising mascots and other retro characters.

Becker sold the company in 2005 to current CEO Brian Mariotti, who expanded the company’s portfolio through licensing deals for hugely popular characters from comics, movies and TV shows.

Major retailers, such as Amazon, Target and Walmart, were lined up to sell Funko products.

In 2010, Funko debuted its now-iconic Pop! line of vinyl figures with oversized heads and giant eyes.

The company opened its flagship 17,000-square-foot store and new headquarters in the old Bon Marche building in downtown Everett in 2017. That same year, Funko went public on the Nasdaq Global Select Market.

In 2019, Funko opened a second store in November on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles.

Bright ideas

A company saying is, “Everyone is a fan of something.” They want a trinket that displays their pop-culture interests: comic book heroes, music icons, sports stars.

More often than not, the market determines the projects Funko’s artists work on. That can be a retailer telling Funko representatives about customer requests for a certain “Star Wars” character, or Disney informing them of a soon-to-be released movie.

But sometimes, the company seizes on a moment.

“The real specialty of Funko is we can respond quicker to what’s happening,” said Butcher, who has been with Funko for more than six years after working at Disney and Pixar.

Marvel’s “Guardians of the Galaxy” was a blockbuster that thrust a talking alien raccoon and a dancing sapling into the cultural consciousness. The latter, baby Groot, was kept a secret by the studio. Funko scrambled to design and sculpt a figure the day the movie hit theaters. In one of the fastest turnarounds by Funko, the toy was in stores about three months later.

Another example is Pickle Rick from the animated series “Rick and Morty.”

“We had no idea it was going to be that funny,” Butcher said.

Funko had designs ready for approval within 48 hours after the episode introducing Pickle Rick aired.

Partnerships and licensing deals allow for such swift response. But when it’s another company’s intellectual property, Funko can be left in the dark.

Such was the case for every toy company after Disney’s TV series “The Mandalorian” debuted and gave the world “baby Yoda,” an infant that appears to be the same species as the cantankerous bog-dwelling Jedi master.

The company’s rendering team regularly mocks up digital product prototypes for presales and social media hype. That’s how Funko posted an image looking like a physical baby Yoda toy to its Instagram, even though the product had not been manufactured.

Other times, the idea comes from a single Funko employee.

Designer Erika Flak pitched a toy line based on legends and myths to company executives. She presented them with 70 creatures, from space aliens to sasquatch. None is owned as intellectual property, nor subject to licensing rights.

The execs chose a dozen, mostly from Greek mythology, for production.

“I’m not the first person to pitch myths,” Flak said. “But I was here at the right time, and I did a lot of research.”

As Flak worked on the Funko Pop! Kraken, she referred to photos of octopus and squid, and drawings of the mythological kraken, an enormous cephalopod-like sea monster that destroys ships.

Early drawings showed monsters with snarling mouths, some with sharp teeth, some with narrowed eyes and a menacing look, and some with a shell like a nautilus. The creature was in an aggressive attack pose, instead of standing vertically like most Pop! characters.

“You either make it a squid or you make it a monster,” Flak said.

With feedback from Funko executives, Flak then drew a standing, tentacled, ship-grabbing blue-and-pink version of the kraken, with open, round eyes. She had the rare ability to pick its colors because it wasn’t a well-known character like Iron Man or Wonder Woman.

Like most Funko artists, Flak displays a Pop! of each of the characters she has designed at her cubicle.

Shape shifters

The next step is sculpting.

Like the analog skills of yesteryear, digital sculpting involves the manipulation of shape.

Instead of clay, Funko’s sculptors use Wacom Cintiq touch-screen computers, stylus pens and ZBrush software that can toggle dozens of manipulations in seconds with a few keystrokes.

“You take a shape and you mush it around until it looks good,” sculpting lead Anna Corcoran said.

A vast digital archive of toy designs gives Funko starting points for new products. The sculptors can take a base Batman and adjust it in thousands of ways to make a new toy. Or they can start with what’s called a base mesh, a mostly featureless male or female figure, and build upon its shape.

To demonstrate what she does, Corcoran moved a base male figure’s arm from shoulder to elbow, its leg from hip to knee, and pulled mass from the head to give it horns. It took her only a few seconds. But real projects can take days, depending on the complexity. A single character wearing a shirt and pants is simple, but recreating a movie scene demands a lot of detail and time. Funko’s artists refer to images and videos of characters while they work.

The next team to work on the toys determines how the 3-D digital model can be manufactured into a toy to display on your shelf.

“Our job is to cut them up,” said Kylie Cave, one of the output specialists. “We try to keep them as beautiful as possible.”

Pulling up one character on her computer, Cave showed it will be assembled from five pieces.

The Cinderella’s carriage she worked on had 15 pieces. Cave determined how best to manufacture it based on its form and function. She said the axles of the carriage demonstrated the problem-solving common in their office. The vines-turned-into-wheels have a tip protruding from the center. She had wanted to keep that as one piece with the axle, but because of the thin curling vine for the wheel, it would be too weak.

“A lot of output is thinking about how strong a piece is going to be,” Cave said.

A hand-painted model needs notes or approval from each artist who worked on the project, before it goes to manufacturing.

All of the digital files and specifications are transmitted to factories in China and Vietnam, where a mold is made and paints are mixed and applied to the figures. It’s one of the longest steps in the process, Butcher said.

Funatics await

Once manufactured, the toys are sent back to Funko on cargo ships through the ports of Everett and Seattle. On rare occasions, the company ships them by plane for special events, such as San Diego Comic-Con.

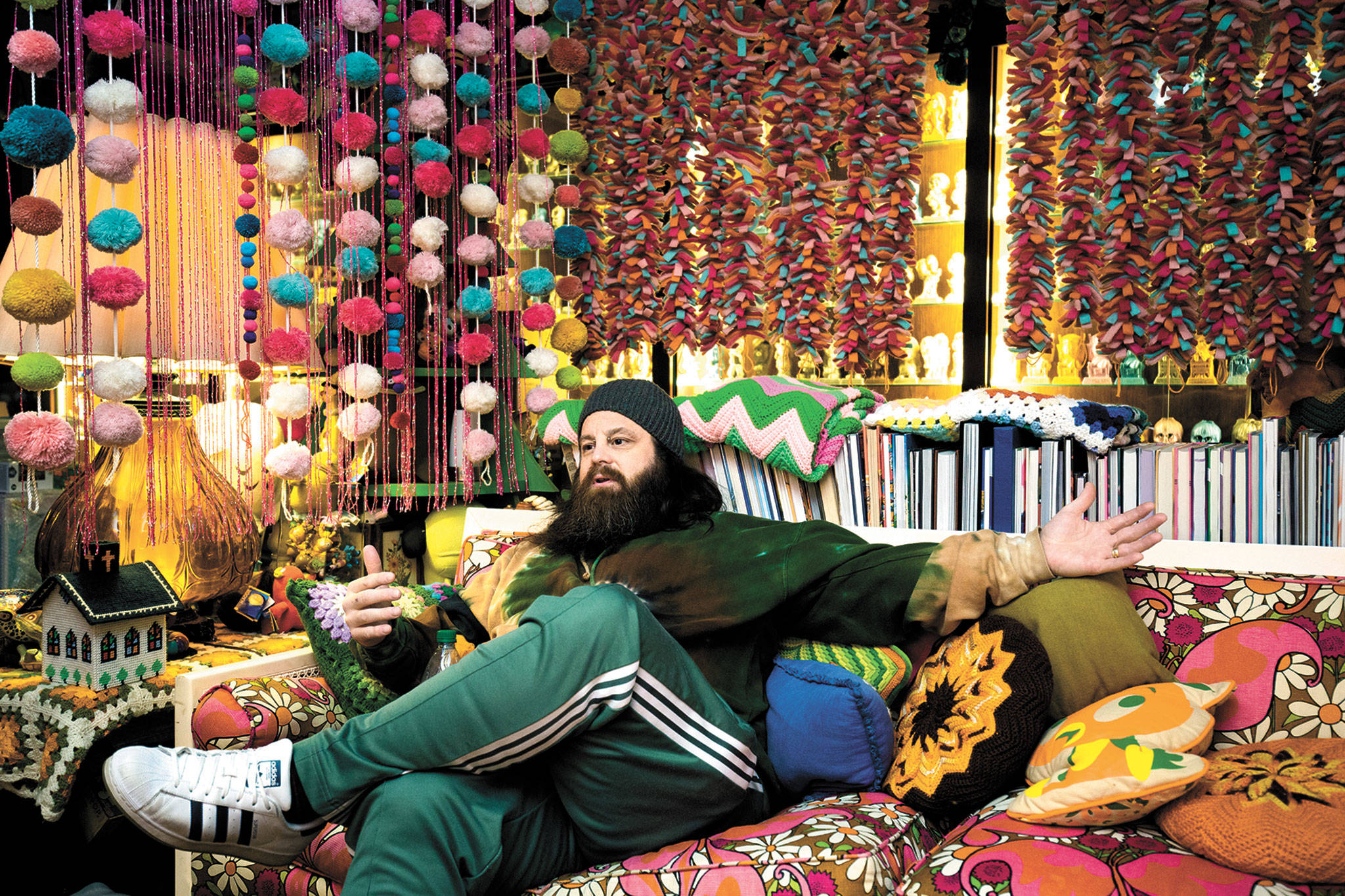

Then the Dorbz, Minis, Plushies and Pop! characters are dispersed around the world, ready for store shelves and the hordes of Funko Funatics — the name Funko’s most ardent customers gave themselves — eager to snatch them up. Like potato chips, Funko customers can’t stop at just one. Many have thousands of the figures in their collections.

“They always have something you want to buy,” Steve Pasierb, president and CEO of The Toy Association, a nonprofit trade association in New York City, told The Daily Herald in 2019. “They’re going in all these different directions because they follow trends and they’re on top of trends.”

Butcher, the vice president of creative, put it this way: “If we do some rare, obscure thing and someone buys it, that’s the gateway drug.”

Washington North Coast Magazine

This article is featured in the spring issue of Washington North Coast Magazine, a supplement of The Daily Herald. Explore Snohomish and Island counties with each quarterly magazine. Each issue is $3.99. Subscribe to receive all four editions for $14 per year. Call 425-339-3200 or go to www.washingtonnorthcoast.com for more information.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.