By Jesse, Everett Public Library staff

I talk a lot about books written for children and teens. They are the core group I serve at the library; I spend a lot of time with books intended for this audience. It helps ensure that I am prepared for any questions that come my way and that I can always hold my own and suggest new titles when I chat with our young readers in the library. None of this is a complaint – I greatly enjoy my time with children’s books, and firmly believe that some of the strongest, most important, and empathy-building literature today comes from the world of YA.

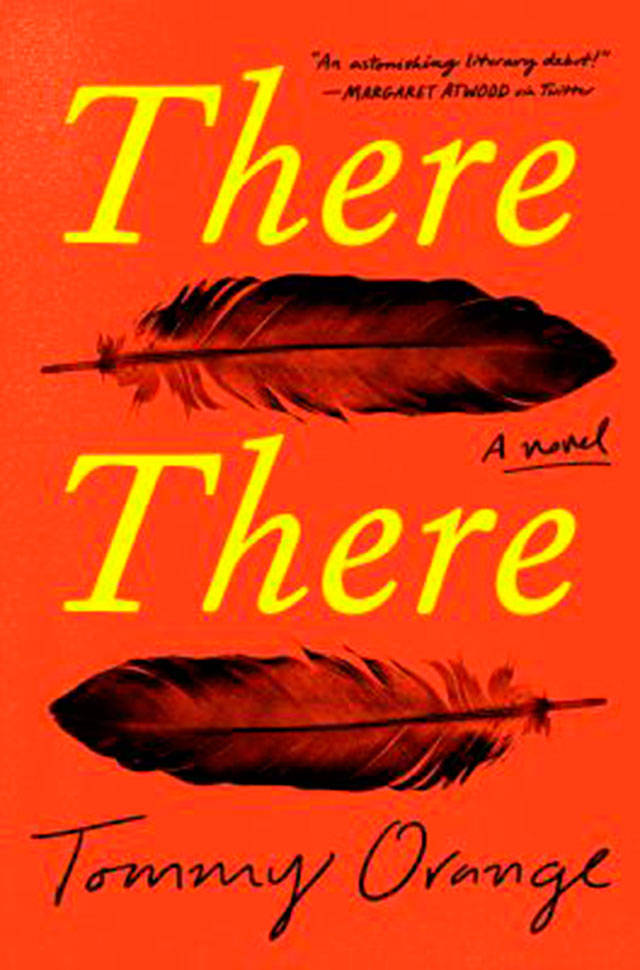

On occasion, however, I like to treat myself to a book actually intended for an adult audience. Usually these are books by authors I enjoy or novels belonging to genres I can’t resist, but every once in a while buzz builds around an author and I can’t resist the hype. It was mounting excitement for Tommy Orange’s writing that led me to his debut novel, There There. To say this novel blew me away is a massive understatement. By the second page of the prologue, I was hooked. By the beginning of chapter one, I was picking my jaw up off the floor.

There There centers on the city of Oakland, California in the days, weeks, and months leading up to a major powwow. It follows twelve different characters, all of whom identify as Native or come from Native descent and have had different experiences as Urban Indians in a gentrifying city. There’s a young boy who has learned traditional dances from YouTube and is determined to dance at the Powwow and a teenager whose life has been framed by violence and seems to be hurtling towards the Powwow at devastating speed. There are characters who have suffered from addiction and fought their way back, some who have fought for a country that has always sought to erase them, some raised around tribal tradition and others who are just beginning to discover their roots. Orange slowly but brilliantly weaves spider-webbed connections between these characters, masterfully uncovering how these disparate lives will come together.

Beyond the compelling narrative, there is so much to praise about this novel. Orange considers identity with a deft touch, making a difficult concept accessible without diminishing its complexity. Through his character’s experiences, he dissects the ways that Native people are made to feel too Indian or not Indian enough. He explores self-discovery and self-loathing, kindness and cruelty, abuse and tender love, all side-by-side but without condemnation. Orange is able to touch on traumas that many groups experience like bigotry, cultural appropriation, and gentrification, and make them feel simultaneously universal to oppressed populations and specifically and undeniably Indian. And he manages to weave together the history of Native activism in America, the many abuses that Native people have suffered, and the ever-evolving effects that generations of systematic and cultural genocide have had on a people.

Then there is the writing itself. I’m not sure I can do justice to Orange’s skill, his ability to write a paragraph that leaves me staggered without being ostentatious. There are writers who are praised for their terse, spare prose and others for their elegant and complex language. I’m not sure quite where Orange falls on this spectrum, but I know it is exactly where I want to be. As I previously mentioned, I knew I was reading something special early in the prologue. I can actually pinpoint the exact moment. While talking about migration to cities, Orange writes:

“We did not move to cities to die. The sidewalks and streets, the concrete, absorbed our heaviness. The glass, metal, rubber, and wires, the speed, the hurtling masses—the city took us in. We were not Urban Indians then. This was part of the Indian Relocation Act, which was part of the Indian Termination Policy, which was and is exactly what it sounds like. Make them look and act like us. Become us. And so disappear. But it wasn’t just like that. Plenty of us came by choice, to start over, to make money, or for a new experience. Some of us came to cities to escape the reservation. We stayed after fighting in the Second World War. After Vietnam too. We stayed because the city sounds like a war, and you can’t leave a war once you’ve been, you can only keep it at bay—which is easier when you can see and hear it near you, that fast metal, that constant firing around you, cars up and down the streets and freeways like bullets. The quiet of the reservation, the side-of-the-highway towns, rural communities, that kind of silence just makes the sound of your brain on fire that much more pronounced.”

I recently heard Glen Weldon, a writer and critic for NPR, draw a distinction when talking about stories that represent diverse experiences. To paraphrase, he said that we shouldn’t talk about stories that haven’t been told before — even if they did not reach our ears, they’ve likely been told. Instead, we should talk about these as stories that we haven’t heard yet. There There tells a kind of story I hadn’t read before, and Orange tells it with intelligence, heart, dexterity, and a swagger that makes it feel absolutely essential.

Visit the Everett Public Library blog for more reviews and news of all things happening at the library.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.