By Michael Dirda / The Washington Post

One hundred years ago — on Aug. 9, 1919 — All-Story Weekly published the opening installment of a serial entitled “The Curse of Capistrano.” Set in a highly idealized Southern California during the early 19th century, when Spanish grandees ruled vast estates and Franciscan missions brought Christianity to the indigenous population, the novel introduced a new adventure hero, the masked avenger of the downtrodden and oppressed, the daring and debonair swordsman Zorro.

A year later, Douglas Fairbanks starred in an acrobatic silent film adaptation of the novel, retitled “The Mark of Zorro.” In the half-century that followed, this wily fox — which is what “zorro” means in Spanish — grew nearly as famous as Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan, another alumnus of All-Story (the lord of the jungle first appeared in its pages in 1912).

In my own childhood, little boys in swimming trunks would inevitably practice Tarzan’s chest-thumping victory cry, just as they would always pick up anything roughly resembling a sword and quickly slash the air with three strokes to make a Z, the sign of the California Robin Hood. In the late 1950s, Zorro grew especially popular because of a Disney television series featuring handsome Guy Williams as the daredevil highwayman. Even now, I can remember the thrilling words of the show’s musical opening:

Out of the night

When the full moon is bright

Comes a horseman

Known as Zorro!

When Johnston McCulley published “The Curse of Capistrano,” he clearly didn’t expect to write more stories about its protagonist. At the end of the novel, he reveals — what any reader will have guessed much earlier — that the languid aesthete Don Diego Vega is actually Zorro. What’s more, McCulley obviously copied this central plot device (as well as Zorro’s league of noble caballeros) from Baroness Orczy’s “The Scarlet Pimpernel.” (In that thrilling swashbuckler, the foppish, slightly dim Sir Percy Blakeney is secretly the intrepid Scarlet Pimpernel, whose guerrilla actions help save the innocent from the guillotine during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror.)

Over the course of his pulp-writing career, McCulley (1883-1958) created many unlikely crime fighters, the most improbable being the Crimson Clown, a costumed avenger who actually dresses in a red clown outfit. You really can’t make this stuff up. Still, he regularly returned to his masked hidalgo.

In 1922’s “The Further Adventures of Zorro,” the villainous Captain Ramon is resurrected from “The Curse of Capistrano” so he can plot with a band of pirates and kidnap Lolita Pulido on the eve of her wedding to Don Diego. To rescue her, Zorro must ride again. In terms of pure adventure, “The Further Adventures” is even more exciting — faster-paced and more varied in its action — than the more romance-oriented original. At one point, Senorita Lolita is offered an unbearable choice: Marry the odious Ramon or watch her beloved Diego be tortured to death.

As a prose stylist, McCulley isn’t likely to be mistaken for the creator of a far more famous Lolita. He’s also blithely inconsistent. In the later stories, the identity of Zorro has again become a mystery (except to Don Diego’s aged father, Don Alejandro, the family’s mute servant Bernardo and the old monk Fray Felipe). Fat Sergeant Garcia can appear as either a buffoon or an implacable enemy (eventually branded with the dreaded Z on his forehead) or even as a self-sacrificing friend.

In “The Sign of Zorro,” Lolita turns out to have died of a fever shortly after her wedding to Diego, who subsequently mopes around the hacienda until the beautiful Panchita Canchola begs for his help and he dons his mask once more. At that novel’s end, the lovely senorita appears set to become a second Senora Vega, but her flashing eyes must have lost their dazzle since we never hear of her again. In the short stories of the 1930s and after, romantic subplots are usually jettisoned for straightforward tales of intrigue and derring-do.

In recent years, some pulp magazine stalwarts, most notably Dashiell Hammett and H.P. Lovecraft, have been canonized by the Library of America. That’s not likely to happen to Johnston McCulley who, except for his luck in creating Zorro, is merely a competent hack — which doesn’t prevent him from being fun to read. Still, you may need to make allowances. McCulley’s blue-blooded caballeros are models of chivalry (except when one goes bad), while his peons and “red natives” are either abused, ignored or treated paternalistically. Zorro’s vigilantism, like that of his comic-book successor Batman, can now appear, shall we say, problematic.

It also seems oddly punctilious that an outlaw is always addressed as Senor Zorro and shocking that a Franciscan monk would be whipped in a public square for supposedly swindling a merchant. And are we tacitly meant to regard the poetry-loving Don Diego, with his dainty handkerchiefs and repeated expostulations about “these turbulent times,” as an effeminate gay man? It’s only a step to George Hamilton’s campy cult film, “Zorro, the Gay Blade.”

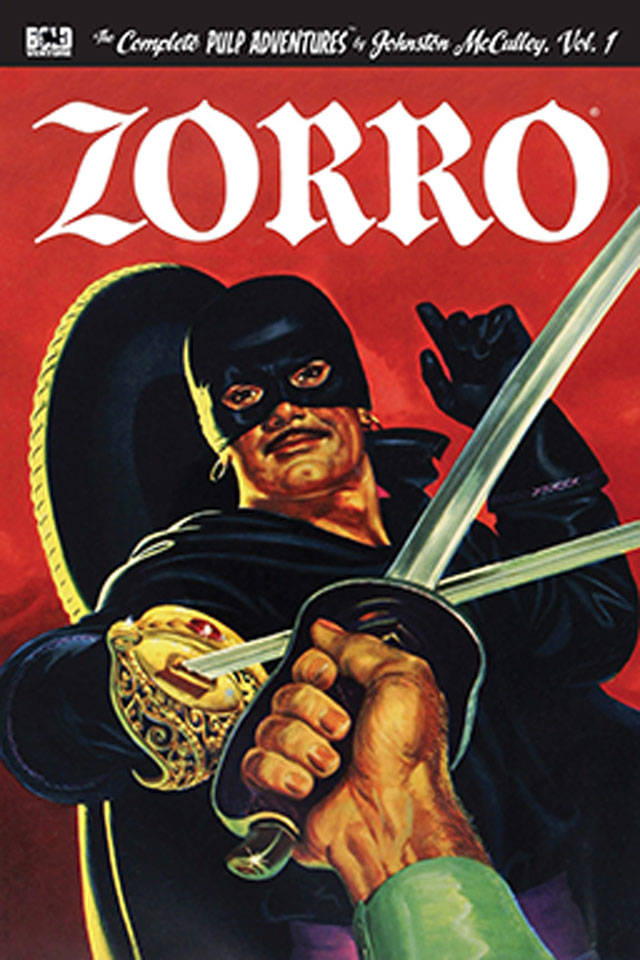

In the past, anyone who wanted to enjoy McCulley’s Zorro stories would need to track down their original magazine appearances. No longer. Bold Venture’s matched set conveniently reprints the whole corpus, along with contemporary illustrations or newly commissioned artwork. Each volume opens or closes with a useful Zorro-oriented essay on, for example, early California history, notable films (such as Antonio Banderas’ 1998 “The Mask of Zorro”), McCulley’s seemingly amnesiac inconsistencies and the market in toys, comics and collectibles. Bold Venture also publishes “Zorro and the Little Devil,” an entirely new thriller by Peter David.

Given that it’s midsummer, you might consider putting aside those emotionally wrenching novels you don’t really want to read or those dispiriting analyses of our national politics. They can wait until September. Now is the time to ride with Zorro.

“Zorro: The Complete Pulp Adventures”

By Johnston McCulley

Bold Venture Press. Six volumes. $19.95 each.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.