A ‘first’: Lake Stevens annexed a big area without public vote

Published 1:30 am Tuesday, August 31, 2021

LAKE STEVENS — Lakeside residents of half a century were among those lassoed into the city in the Southeast Interlocal Annexation earlier this month.

The Snyders moved to a waterfront home on the southeast end of the lake in fall 1972.

“Even though we resided outside the city limits of Lake Stevens, we still considered ourselves part of the community,” Stuart Snyder said.

The Snyders, like many of their neighbors, sent their kids to Lake Stevens schools and have enjoyed shopping at local stores, attending community events and volunteering where they can.

Stuart Snyder said they watched the community grow from primarily ducks and beavers to the over 35,000 people living there today.

“When this annexation came along, I became perplexed about the manner in which it was achieved,” he said.

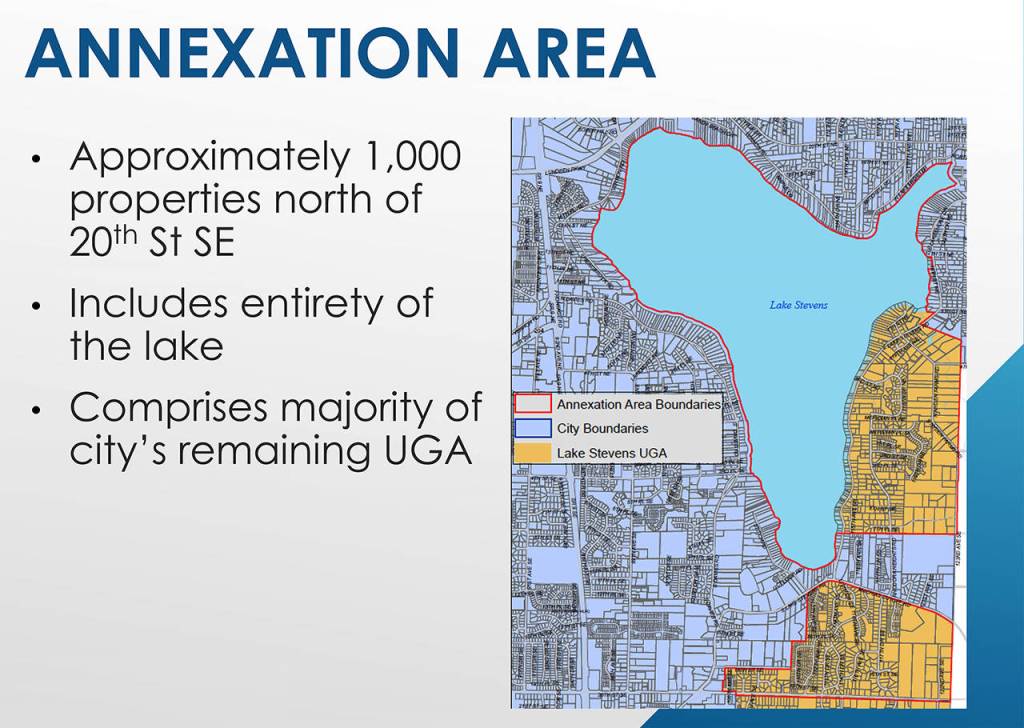

The Southeast Interlocal Annexation, which includes the majority of the city’s remaining urban growth area west of 123rd Avenue SE and north of 20th Street SE, was, in some ways, historic: It advanced without a public vote.

“We were the first city to do it,” said Kim Daughtry, Lake Stevens City Council president. “We were also the first ones to take the heat for doing what the state allowed us to do.”

The annexation did not require a vote of residents affected by the boundary change because it used a new method authorized by a state law which became effective in June 2020. The law allows cities and counties to sign an interlocal agreement to allow unincorporated land to be annexed within designated urban growth areas.

The annexation area includes an estimated 1,000 properties, and the 1,000 acre lake itself.

“There’s this kind of common feeling that there’s just nothing we can do about it,” said Mike Flathers, a resident in Rhodora Heights, one of the recently annexed neighborhoods.

Flathers was among residents urging an advisory vote. Without one, the residents had nobody to advocate for them, he said.

In one of the first initial council meetings about annexation, “there’s like 80 people that were against the annexation, and (a councilmember) said … ‘I’d encourage you all, if you’re upset about this, maybe find a different city councilmember’” to vote for, Flathers said. “(But) we don’t get to vote … we don’t get to elect council members so we don’t have any representation in your government. And you’re kind of forcing yourselves on us and we don’t consent.”

The process began in July 2020, when the City Council approved a resolution authorizing the city to begin negotiations with Snohomish County on an interlocal agreement.

State law requires that other utility providers be offered the opportunity to join the interlocal agreement and the Lake Stevens Sewer District opted to join as a party in the Southeast Interlocal Annexation.

City, county and sewer district staff developed the interlocal agreement and finalized the language in February.

The Lake Stevens City Council then passed Ordinance 1112 — authorizing the mayor to sign the agreement between the city, county, and sewer district, annexing properties within the Southeast Interlocal Annexation area — in March.

On Aug. 13, the city shared a Facebook post and sent letters welcoming the new residents.

They now have access to the city’s police services. Fire protection, school district boundaries, sewer and water, however, are unaffected by annexation.

Changes for those recently annexed into the city include an increase in property taxes, from a typical levy rate for an average residence per $1,000 of about $9.70 in Snohomish County to about $10.20 in Lake Stevens, in addition to utility excise taxes that the county does not have.

The city will also inherit stormwater and road maintenance, lake and surface water management and building, planning, zoning and permitting in newly annexed areas.

Daughtry said those recently annexed into the city can expect to receive road and sidewalk improvements.

Public Works “is already making that list,” he said. “But it’s not going to be an overnight thing.”

Dan Dziadek, a Lake Stevens resident who gathered enough signatures to put the Southeast Island Annexation up for a vote, said he hoped the city would agree to offer his annexation area concessions in the form of sidewalk improvements, amendments to city code that would adjust the minimum accepted traffic level accepted in the city as well as a reduction of the allowed density of housing in the 2018 Pellerin annexation area.

Shortly after his neighborhood was annexed, a development was planned.

Daughtry said he acknowledges that some newly annexed residents are concerned about development, but he said “it’s not a done deal where developers can come in and run rampant.”

The city assigned zoning within the urban growth area that was intended to match the existing county zoning designations in 2019.

Newly annexed residents can vote for city representatives and political signs have already started popping up across neighborhoods.

Lake Stevens has undergone a series of annexations since 2002. The biggest, which brought in an estimated 10,000 people, happened in 2009.

Between 2000 and 2010, the city quadrupled in population and, according to the 2020 Census, it now sits near 36,000.

Calm River, a private consulting firm, is conducting a door-to-door census of newly annexed residents. According the Forecasting & Research division of the state Office of Financial Management, the city has 30 days to complete the census.

Daughtry, who’s been on council for 12 years, said these annexations shouldn’t come as a surprise. “It’s been the plan to get to ‘one city around the lake,’” he said.

Some residents do not feel the most recent annexation included enough public input.

Lake Stevens resident and former planning commissioner Tom Matlack said he felt the pandemic affected residents’ ability to engage with the city during the process.

“I was not convinced — I’m still not convinced — that people had a fair and prudent exchange of information on the whole thing,” he said. “Everybody likes to blame everybody but it was really the whole COVID thing. Zoom meetings are really hard to do.”

The city hosted an informational meeting about the annexation on Zoom in September 2020 and a subsequent public meeting in early December.

Dziadek said prior to the pandemic, getting involved in his neighborhood’s annexation wasn’t easy, either.

“It took a lot of research — which I don’t think a lot of people do, going that deep and reading (state laws) and interpreting them and then going to City Council meetings,” he said. “No, I don’t think it’s an easy process. I think it was very time consuming and burdensome.”

Jason Reber, who takes care of his 89-year-old grandmother living on the southeast side of the lake, said he received the welcome letter but didn’t know much else about what it means to be annexed.

His grandparents were always involved in the community, since they built their house on the lake in the late 1970s. His grandpa, Ron Reber, used to teach drivers education in the city.

“I always felt that we were one community around the lake,” Snyder said. “What they were hyping was one administration around the lake — and I have problem with that. But I’m hopeful. I’m hopeful it all turns out for the best.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @BredaIsabella.