EVERETT — They’ve labeled it an epidemic.

Now, leaders in Snohomish County want to treat widespread opioid abuse as a true health crisis.

Public health, law enforcement and emergency management officials on Monday rolled out a plan to confront the addiction ills plaguing Snohomish County, a community grappling with heroin and prescription drug abuse like thousands of other places across the nation. It’s not unlike how they might respond to an outbreak of infectious disease.

“The opioid epidemic is often referred to as a public health crisis, and that’s certainly true,” said Dr. Mark Beatty, health officer for the Snohomish Health District.

For his agency, it is not a problem that can be solved alone. “It requires each of us working together with a shared purpose,” he said.

The response draws upon lessons learned working together for months after the deadly 2014 Oso mudslide.

A press conference at the county’s administration building showcased what people from various agencies have been doing behind the scenes for months.

The problems span many agencies and disciplines. For example, shutting down a homeless encampment might take law enforcement to clear out the trespassers; public works crews to clean up messes left behind; and public health officials to assess any environmental damage from used needles and human waste.

That’s after police and paramedics have become familiar with the area from crime and medical emergencies.

Since 2004, the county has opened more than 245 nuisance property investigations, including homeless encampments and squatters who have taken over empty homes that are in bank foreclosure.

By collecting more data about what various agencies are seeing, officials hope to find which approaches work, and which don’t. They’ll pool information on overdose deaths and saves. They hope to get a better read on nuisance properties and drug houses.

Another goal is reducing negative impacts on health, including hepatitis C, which has increased 53 percent in the county from 2016 numbers, and other infectious diseases common among addicts. They’re trying to steer more people into treatment.

One gauge of how widespread the issue is has been the collection and disposal of used needles. The health district is on pace to collect 2 million needles this year.

Law enforcement will continue to work on lessening the flow of opioids into the community, while clamping down on property crimes and other activity that stems from abusing opioids.

“We’ve learned in law enforcement that we can’t arrest our way out of the opioid epidemic,” Sheriff Ty Trenary said.

Collaboration will be key in addressing the problem at a local level, he said.

Last year, the sheriff’s department’s Office of Neighborhoods found housing for 57 people and detox services for another 85. At the same time, the county is examining “how we can help people detox better” while they are in jail, Trenary said.

The sheriff rejects suggestions he’s heard that law enforcement shouldn’t help addicts. He wonders if people would have the same response if they were to go with him to the camps and see the suffering themselves. He also said the problem affects every community across the county, not just parts of Everett and other high population areas.

As law enforcement, “we don’t play God” in deciding who to help, he said.

Since 2015, after law enforcement agencies countywide were trained to give Naloxone nasal spray to reverse overdoses in medical emergencies, more than 120 lives have been saved.

Unlike a natural disaster, county leaders have not declared a formal emergency, but they have promised to put more resources toward solving the challenges of addiction.

“Our guiding principles for this effort are collaboration and coordination for the benefit of all of our residents,” County Executive Dave Somers said. “We are a community coming together.”

Somers has directed the county’s Department of Emergency Management to partially activate its Emergency Coordination Center to support this effort. The center typically is used to address natural disasters, including floods and fires.

The community needs coordination, and compassion, to respond to the crisis, Somers said.

“No one chooses to be a heroin addict or get hooked on prescription pills,” he said.

“We must try to save all lives and treat every human as a family member,” he added.

The county executive has seen addiction within his own family circle, including, he said, an in-law who was hooked on prescription drugs and a brother who has been clean for a number of years.

“The folks I know who have addictions are good people” living with problems, he said.

A new website provides more local resources for the public. It has background about opioids, contacts for seeking treatment and should soon be updated with more data. One section gives business owners direction on issues such as what to do about used needles or nuisance properties.

They’re calling it the Opioid Response Multi-agency Coordination Group, or MAC for short.

More info: www.snohomishoverdoseprevention.com.

Noah Haglund: 425-339-3465; nhaglund@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @NWhaglund.

Opioid survivals

The emergency room at Providence Regional Medical Center Everett treated 688 overdoses through August of this year.

• Six patients were under age 6.

• 13 were older than 90

• The age groups that represented the largest number of patients were 21 to 30 and 51 to 60.

(Source: Providence Regional Medical Center Everett)

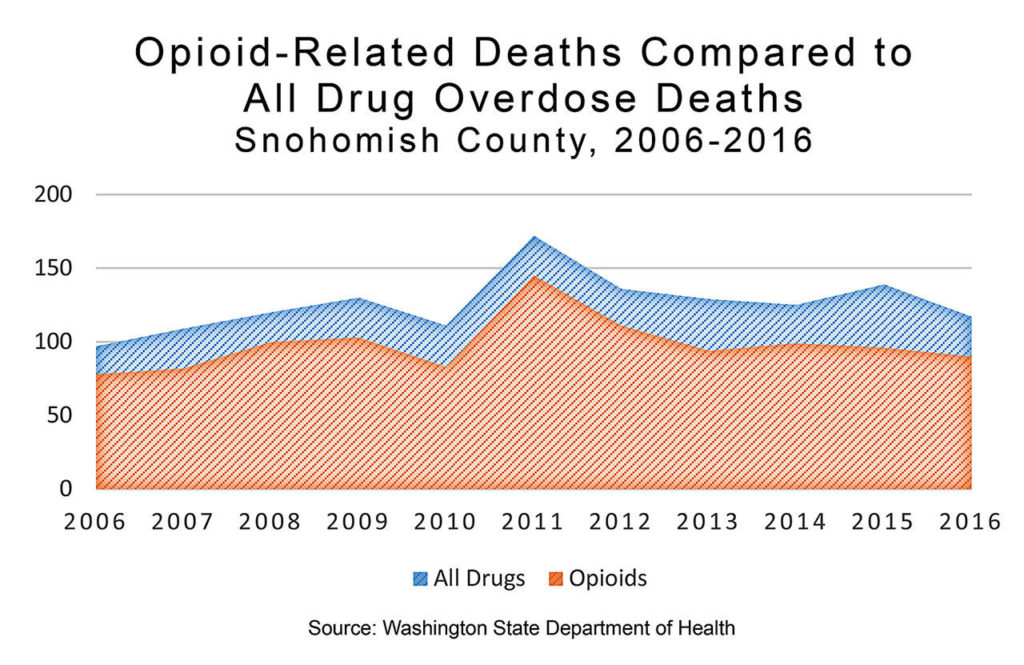

Opioid deaths

2016 – 90 overdose deaths in Snohomish County.

Of 90, 44 were heroin-related, 57 were attributed to prescription opiates (some cases involved a combination of drugs)

Of the 57 non-heroin opiate deaths last year, 13 were from fentanyl or other synthetic drugs.

Statewide 2016, total fatal opiate overdoses: 694

(Source: Snohomish Health District)

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.