MUKILTEO — At Compass Health, Amanda Steffen helps patients with severe mental illness. But after nine years on the job, she said the nonprofit needs to take care of its workers, too.

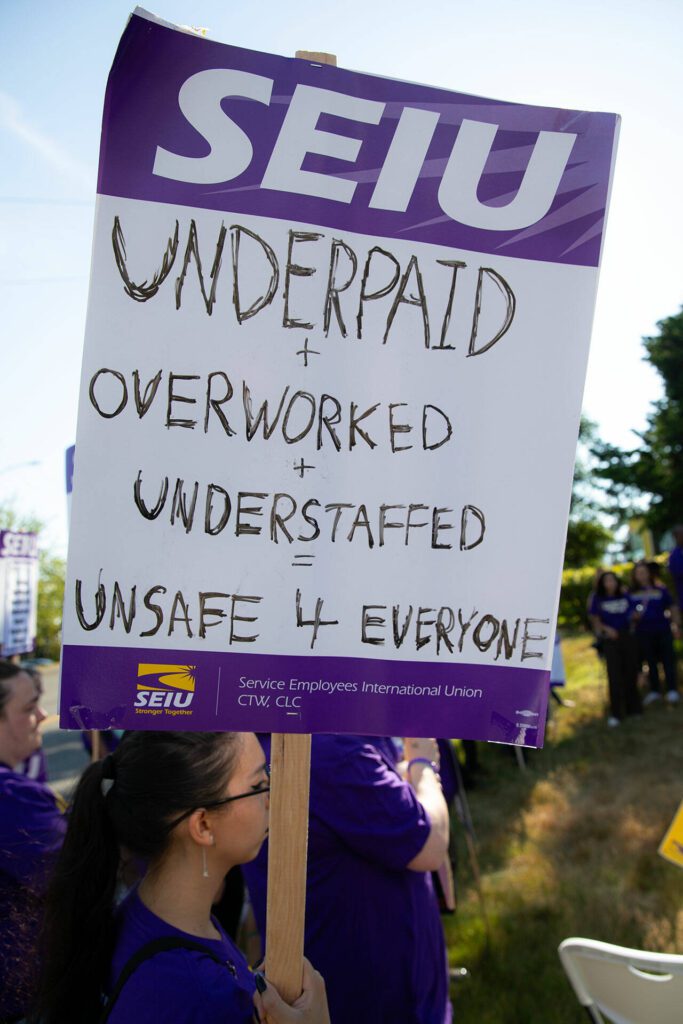

On Thursday, Steffen picketed with dozens of clinicians, counselors, nurses, behavioral health care staff and community members at Compass Health’s inpatient clinic in Mukilteo. In total, more than 350 Compass Health workers picketed in Mukilteo and Bellingham this week to pressure the nonprofit to improve wages and benefits.

“When someone’s loved one is in crisis, we’re the ones who take care of them,” said Steffen, a psychiatric technician. “We want our employer to acknowledge that, and that we deserve to be able to take care of ourselves and our families, as well.”

Compass Health provides behavioral health care to low-income families and Medicaid patients at 26 locations across Snohomish, Skagit, Whatcom, San Juan and Island counties. For over a year, the Everett-based nonprofit and workers represented by Service Employees International Union Healthcare 1199NW have negotiated over a new labor contract, with wages and benefits a major sticking point.

Since October, the nonprofit has offered union workers a minimum wage increase of 6%, with increases up to 22% for some positions including clinicians, care coordinators and nurses. Workers argue the raises still won’t provide a living wage for some lower-paid staff, and the nonprofit’s offer includes a new health insurance plan that raises deductibles from $100 to $500.

The proposed insurance changes are intended to help Compass Health provide higher wages, according to a statement on the nonprofit’s website.

Compass Health, like other health care providers across the state, has struggled to overcome a workforce shortage and poor insurance reimbursement rates. The nonprofit ended its past fiscal year nearly $3 million in the red. Compass Health executives have said the nonprofit will continue to flounder until the state changes its funding model for behavioral health care.

Last year, Compass Health saw a turnover rate of nearly 22%. Workers said the nonprofit fails to hire and retain clinicians and other essential staff because of low pay. Lengthy contract negotiations have exacerbated the problem, CEO Tom Sebastian said in an emailed statement Thursday.

A single mom, Steffen said she’s had to work other jobs on top of her five or six weekly overnight shifts at the Mukilteo clinic. And peer counselors, some of the lowest-paid at the nonprofit, start at $17 an hour. As of last week, the average hourly pay for a peer counselor in Washington is $21.05 an hour, according to ZipRecruiter.

“They’re having to make decisions like, ‘Do I have surgery, or pay rent this month?’” said Chelsey Dyer, a school-based Compass Health worker based in Friday Harbor on San Juan Island.

Last year, Dyer advocated alongside other Compass Health workers in Olympia for increases in health insurance reimbursement rates. Sebastian said the money would go to frontline worker pay.

“We are advocating for a 15% increase in the Medicaid and non-Medicaid rates so that we can pass those along to support our staff,” he said in April 2023. “This will help us recruit staff to our agencies to provide these critically needed services, and also help us retain staff who are really working hard under very difficult circumstances, trying to give community members the services they need when they really don’t have the capacity and the resources that are necessary to do the job.”

State legislators approved a 15% increase that began in January, but Compass Health has since pivoted its stance.

“Unfortunately, because of the complexities of the community behavioral health system, fee-for-service reimbursement, years of chronic underfunding and the fact that various programs have different funding sources, it’s not a simple pass-through equation,” Sebastian said in an emailed statement Thursday. “While we’re grateful for these legislative efforts, the fact is that these rate increases have been playing catchup with our expenses.”

Compass Health spent 56.4% of its annual expenses on payroll this past fiscal year, according to tax filings. About $2.2 million, or 2.9% of total expenses, went to executives.

Dyer pointed out executives “gave themselves” raises in the 30% to 50% range in 2021. Sebastian’s salary, for example, has increased 47.5% since 2021, to more than $350,000 last year. Meanwhile, other workers have seen raises in the 5% to 30% range.

“It’s reprehensible,” said Dyer, who has worked at the nonprofit for almost four years. “Our market value seems to be barely scraping the surface of minimum wage.”

Executives have taken unpaid furloughs this past year to cut costs, Sebastian said.

In 2020, Compass Health closed three outpatient sites in Marysville, Monroe and Snohomish after a drop in client visits. In 2022, the nonprofit closed the only behavioral health crisis center in the county, cutting 29 jobs and leaving 254 clients to seek support elsewhere.

Then in April, the nonprofit laid off dozens of employees and shuttered its child and family outpatient therapy office in Everett, with the option for patients to go virtual or visit other Compass Health locations. Before the closure, therapists there served about 300 families, with some taking on 50 clients at a time. The nonprofit has no more plans to lay off workers or close programs, Sebastian said.

Meanwhile, mental health care needs in Snohomish County are only rising. The county has named mental health care access and childhood trauma prevention as top health care issues. Nearly a quarter of students have experienced “potentially traumatic” childhood events, according to a county-wide health assessment published last year.

Compass Health workers argue the nonprofit’s economic strategy ultimately hurts the patients it’s trying to help.

“When we have to close a facility, it reinforces people remaining in crisis,” Dyer said. “And when we have staffing struggles, it’s hard for our patients to achieve mental health stability.”

Compass Health is in the second phase of its Broadway Campus redevelopment project, a comprehensive health care and housing hub in downtown Everett. Next year, the nonprofit is set to open a 72,000-square-foot intensive behavioral health facility that cost $68.5 million in donations to build. Sebastian said he plans to hire 200 “world-class” employees to staff the facility 24/7 and serve about 1,300 patients each year.

Sebastian said amid the picketing, appointments at the nonprofit’s clinics will continue without interruption.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Chelsey Dyer’s name.

Sydney Jackson: 425-339-3430; sydney.jackson@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @_sydneyajackson.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.