EVERETT — Growing up at the base of Rucker Hill, Larry O’Donnell would go to Pigeon Creek Beach whenever there was “sunny weather and a cooperative thermometer.”

O’Donnell, now 86, and half a dozen other kids often marched down Laurel Drive, with a few of their mothers in tow. They followed the railroad tracks for a half mile and crossed them where Pigeon Creek No. 1 flows into Port Gardner Bay.

There, the kids swam, dove from logs and built sandcastles in the 1940s.

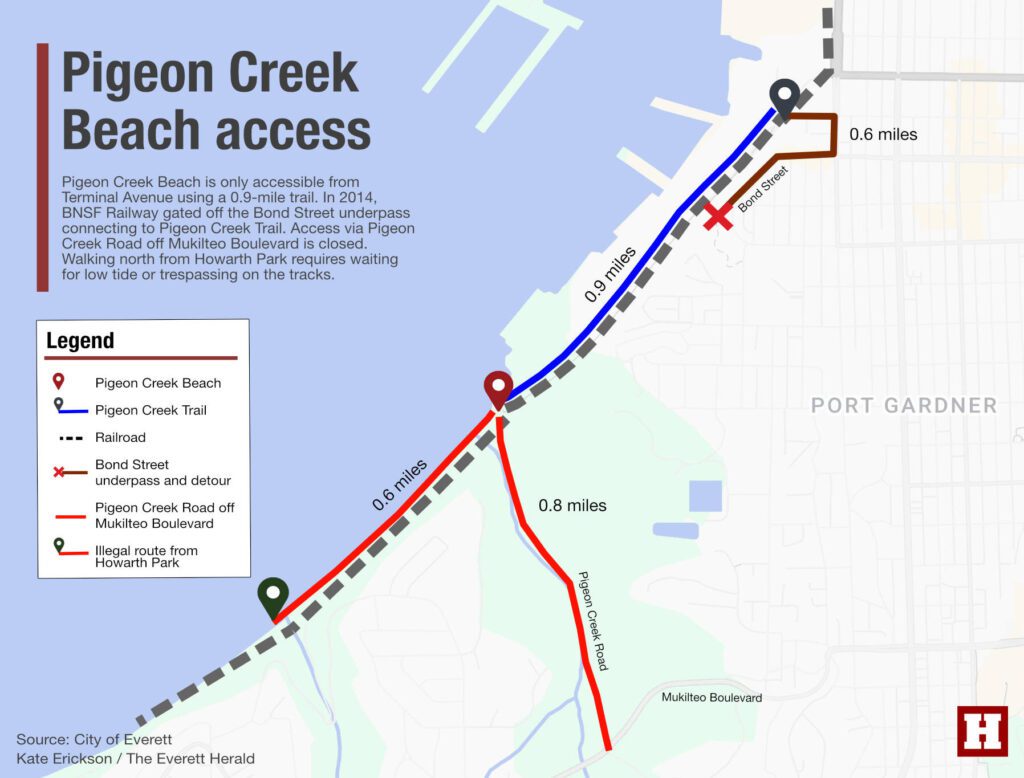

Today, to go to Pigeon Creek Beach, you have three options. Two aren’t exactly legal.

• Walk a shadeless, trash-littered mile of the Pigeon Creek Trail, bordered by razor wire, starting on Terminal Avenue.

• Illegally walk down Pigeon Creek Road, a service road about three-quarters of a mile long off Mukilteo Boulevard. The road, opposite an entrance to Forest Park, has been gated since 2005 with no designated parking “due to declining roadway conditions, vandalism at a sewer lift station, and because it promoted unsafe trespassing across the BNSF Railway mainline,” according to the city.

• Illegally walk 0.6 miles north from Howarth Park by trespassing along BNSF railroad tracks. Unless there’s a low tide, it’s a dangerous path past an active freight and passenger rail line.

Many locals admit to using the illegal routes to get to the waterfront.

Larry O’Donnell’s brother, Jack, said crossing the tracks used to be common.

“We used to just walk down the tracks to get to it, and then just go over the tracks. Railroad’s gotten really nasty about any access,” he said. “But back in the olden days, and I’ll say up until the ’60s at least, (BNSF) didn’t enforce it.”

The city of Everett’s 2019 Shoreline Public Access Plan outlined an ambitious vision for restoring legal access points to places like Pigeon Creek Beach, while creating better pathways along 25 miles of marine and freshwater shoreline from the Snohomish River to Mukilteo. The plan was put together to connect Everett’s neighborhoods, promote economic development and environmental restoration.

But the document cited many obstacles — a lack of funding, private ownership and difficult negotiations with BNSF.

‘The railroad has authority’

The Bond Street underpass serves as a case study of Everett’s struggle to balance public waterfront access with the infrastructure needs of a port-centric economy.

The underpass, the last legal pedestrian crossing from Rucker Hill to Pigeon Creek Trail, closed about a decade ago, when BNSF raised concerns about the safety of residents crossing the tracks to the Pigeon Creek Trail and the beach beyond.

Restoring pedestrian access via Bond Street was “under litigation” and “on-going negotiations” at the time of the shoreline plan, a city spokesperson said, adding negotiations have continued over public access, “with the potential for litigation.”

The idea to close the Bond Street underpass was first considered in 1999, when the city, port and BNSF began drafting plans for the Terminal Avenue Bridge at Everett Avenue and West Marine View Drive. The goal was to eliminate street-level railroad crossings, ultimately improving safety, Port of Everett CEO Lisa Lefeber said in an interview this week.

Then, during the bridge’s planning phase, the 9/11 terrorist attacks put officials on high alert. The federal Department of Homeland Security restricted access in and around the port’s federally secured shipping facilities at the south waterfront.

For each beach access point removed, BNSF had to contribute $300,000 for the Terminal Avenue project.

Meanwhile, the Port of Everett opened the Pigeon Creek Trail in 2005 — a skinny strip of asphalt hemmed in by chainlink fence, with the railroad tracks on one side, shipping containers and massive cranes on the other.

A community group fought to keep the Bond Street underpass open, and so it remained for another 11 years. To improve safety, the city had to build a “cattle crossing” to make people look left and right before crossing, Lefeber recalled.

In 2014, then-City Engineer Ryan Sass explained at a City Council meeting that BNSF’s risk management team saw many people crossing while trains were parked on the tracks. BNSF asked the city to close the underpass to pedestrians. After the city refused, BNSF didn’t ask anymore. The rail company told the city it would close the walking route on its own. A fence went up in July 2014.

BNSF did not respond to emails requesting comment sent to its media email address, via a media form or to spokesperson Muru Murugappan.

The city has little leeway to fight BNSF’s decision, because Everett is considered a “Class I Railroad” city at “the Western Terminus to the BNSF mainline across the nation,” according to the port.

“If this were to happen in Edmonds, even in Mukilteo, there would have to be a public process,” Lefeber said. “The railroad has authority to shut down crossings at their discretion for safety.”

The city tried to reach a compromise with the railroad.

“At this point,” Sass said in 2014, “the city continues to have a dialogue with the railroad to try to get them to reconsider that decision and to be open to a pedestrian-grade crossing of any kind at this location.”

He added that BNSF planned on having longer trains parked for longer periods of time and wanted no “grade-crossing” – where a railroad intersects with a street – at Bond Street for safety reasons.

John Witters opposed the decision in that same City Council meeting.

“From Pigeon Creek to Port Gardner in the west, to Junction Avenue to the east, an iron curtain has descended around Everett,” he told the council. “Behind it are the citizens of the city wanting to get access to their waterfront.”

His son had used the underpass, first on a tricycle, then a bike.

Before the closure, the family would go down to Pigeon Creek Beach weekly in the summer. When the underpass closed, the family stopped going as often. Witters’ son, then 8, couldn’t bike all the way to the Terminal Avenue Bridge.

Nearly 10 years later, Witters still lives in Everett. And he still longs for a shorter ride to the sea.

“My son will be off to college next year,” he said last week. “That’s over seven years of missed recreational activities for my son and his friends at Pigeon Creek. I hope that something can be worked out so that, in the future, families in the neighborhood will be able to enjoy Pigeon Creek, like we did before 2014.”

‘Imprisoned’

The Port Gardner neighborhood stretches from downtown Everett to Pigeon Creek No. 1, with many scenic views of the city, port and bay. Historically, the neighborhood enjoyed easy access to all of these areas.

In 2024, residents feel disconnected from the shoreline. To get to the Pigeon Creek Trail, residents must drive to a parking lot with six spaces and confusing signage at the base of the Terminal Avenue Bridge.

To your left, freight trains a mile long often rumble through the rust- and mud-colored corridor.

To your right, white-and-green gantry cranes tower over motley-colored stacks of containers. Closer to the beach sit loose I-beams, empty wooden spools and security cars with vibrant green mold growing around the windows.

It’s a scene that leaves Jack O’Donnell feeling “imprisoned.”

“It’s pretty unpleasant,” he said.

Lefeber agreed, calling it “the worst possible location for a trail.”

“There’s nothing unfortunately we can do to improve it,” she said, noting the port installed the barbed wire because people jumped the fences.

The trail opens at dawn and closes at dusk. Lefeber would prefer to close it entirely during the winter.

Several Port Gardner residents said the trail has a reputation in the neighborhood as a gathering place for homeless people.

Seeking better health care, Carol Hunter moved here from Texas six years ago. She was also excited about the shoreline.

“But it’s getting there that’s a problem for me,” she said. “I think if more people like you and I would go visit the beach there’d be less, shall we say, trouble?”

‘Millions and millions and millions’

Pigeon Creek Beach sits at a critical point on Everett’s shoreline, with no other public roads for at least a half-mile in each direction.

In the 2019 shoreline access plan, it’s seen as a “particularly important” piece of a 4-mile-long waterfront trail system that could connect downtown Everett to Mukilteo.

The plan envisioned a public trail, 8 to 12 feet wide, that would extend a terrace of rocky seawall into Puget Sound alongside the railroad route. At the point where Pigeon Creek Road approaches the railroad tracks, the plan suggested either an underpass or overpass for pedestrians to reach the beach.

The project has been mentioned in the city’s annual six-year Transportation Improvement Program since 2020. The most recent report projected a crossing from Pigeon Creek Road to the beach would cost $925,000 — an amount the city reported would merely cover the cost of repairing the road.

Lefeber thinks an overcrossing is the only viable option, like the one a half-mile west at Howarth Park. Lefeber said it would more likely cost “millions and millions and millions of dollars, potentially on par or more expensive than the Grand Avenue Bridge.” That’s because the port needs a 35-by-35-by-50-foot “envelope” of clearance to transport airplane parts to Boeing.

Pigeon Creek Road is “unlikely to be reopened unless or until a public crossing of the BNSF Railway mainline were to be constructed at the bottom,” city spokesperson Kathleen Baxter said in an email.

Baxter said the city could not comment on any potential litigation related to the Bond Street closure.

“If this litigation/negotiation results in a resolution requiring Council action, that action will be discussed and acted upon at an open public Council meeting,” she wrote in an email.

The 62-page shoreline plan offered dozens of other concepts for projects: a waterfront boardwalk around the Delta neighborhood; a bridge from East Marine View Drive to Langus Riverfront Park; and an expanded trail network all across Everett’s peninsula.

‘Not everybody can go to Hawaii’

Elsewhere in Everett and around the county, there has been a push for improved waterfront access.

The port has invested over $26 million in new waterfront public access projects since 2006, with a focus on Everett’s marina. The vision is a “balanced working and recreational waterfront” with development at the south end and recreation to the north, port spokesperson Catherine Soper wrote in an email.

Jetty Island, reachable by ferry or private boat, has long offered 2 miles of man-made sandy beach.

In 2014, a new trail opened at Everett city limits, leading to the 1-acre Edgewater Beach and park.

Two years later, Everett restored public beach access at Howarth Park. The city invested $1.5 million in a project to repair a rusting overpass bridge and add sand to Howarth beach and four other locations between downtown Everett and Mukilteo.

In 2023, Meadowdale Beach Park in Edmonds reopened after a $15.5 million renovation. The project rerouted 120 feet of railway onto two bridges, where pedestrian walkways provide easier access to the shore.

Everett’s shoreline plan suggested looking at this example set to see if it can be replicated.

Liz Fox, of Everett said shoreline access could be improved for a seaside city. She pointed out that Bellingham, for example, managed to reclaim industrial spaces for the public.

“That’d be difficult with Everett, because the port is a big part of the economy,” she acknowledged.

She noted the importance of third spaces, where people can socialize and foster community outside of work or their homes.

“It’s important to feel connected to the environment,” Fox said. “Take kids for free outdoor activities.”

Neil Anderson, a longtime Everett resident, said visiting the available beaches shows they’re in great demand.

“On a sunny July or October day, especially if it’s a Saturday or Sunday, you’re not going to park anywhere near (the beach),” he said. “The parking lots just fill up.”

To Anderson, the city must address this need.

“The city population increases and there needs to be more areas for recreation,” said Anderson. “Not everybody can go to Hawaii and not everybody has a beach cabin.”

Aina de Lapparent Alvarez: 425-339-3449; aina.alvarez@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @Ainadla.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.