EVERETT — The last time anyone could recall seeing Rodney Peter Johnson alive, it was 1987, or maybe 1988. He was about 25 years old, working at a Chinese restaurant in the Ballard neighborhood of Seattle, living with a cousin and an aunt along NW 60th Street.

He spent a brief time in jail in late 1987, and then records of his whereabouts dry up.

Johnson wasn’t reported missing until 1994, by a sister who notified a bureau of the Salvation Army in Seattle. Months later, on the afternoon of June 11, 1994, in an apparent coincidence of timing, two men tried to untangle a fishing line on the north shore of Lake Stickney. Among thick lily pads and murky water, they found a man’s body, fully clothed, decomposed so badly his tissue had turned into a kind of soap, known as corpse wax, or adipocere. The process of underwater decay takes months, if not years.

An autopsy showed the man had been shot in the head. It was classified as homicide. He became known to investigators as the Lake Stickney John Doe, an enigma whose name, age, race and other clues to his past dissolved in the shallows south of Everett.

More than 26 years after the body was found, the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office confirmed Wednesday that DNA proved it was Johnson.

His sister and father, too, made an official missing person report to the sheriff’s office, in 1996, but there was little follow-up over the past 2½ decades.

At the time he vanished, Johnson was a grown man.

Investigators believe his remains stayed under the water for years, weighed down by something, while houses and neighborhoods sprouted up near the lake south of Everett.

It’s unclear why the body floated to the surface when it did.

Now detectives are a giant step closer to solving a new mystery.

Who killed Rodney Johnson and why?

Johnson came from a family with many cousins. His mother, June, had three brothers and five sisters. Yet he was about the only cousin Eleanore “Ellie” Perry, 64, of Anacortes, never got to know. Perry, it turned out, is a genealogy hobbyist, and she was well aware that law enforcement has been using the combined powers of family genetic history and crime scene forensics to solve seemingly unsolvable cold cases in recent years.

Earlier this year, Perry gave police permission to use her DNA in criminal investigations through a public genealogy database. It was a decision she weighed for weeks before deciding to check a box saying she would “opt in” — figuring she had nothing to lose.

“You can check me out, I have a clean record,” Perry said. “I don’t have nothing to hide.”

Cold case detective Jim Scharf contacted her earlier this year with an odd question. It was something like, “Of all your cousins, who is most likely to have been missing for the past few decades?”

She told the sheriff’s detective to look at the Johnsons.

Shifting faces

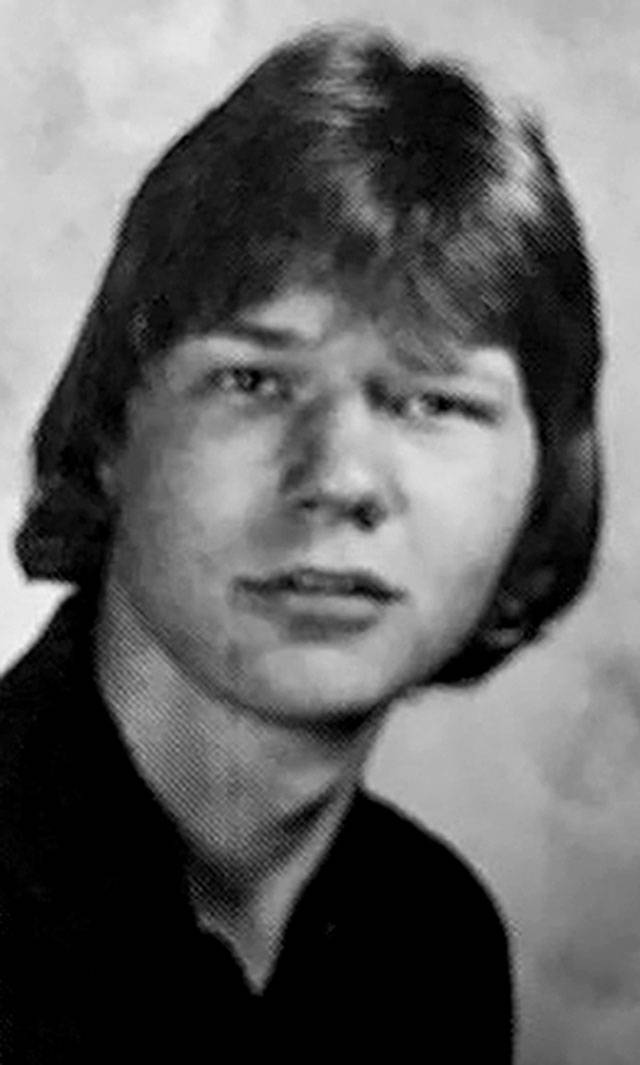

Rodney Johnson’s biography has blurred with time, but some basic facts have survived. He was a foster child, one of four brothers with a half-sister. He attended Darrington High School, and he worked at a Seattle restaurant called The Golden Dragon, according to the sheriff’s office.

As a young man, Johnson had a short rap sheet for burglary as well as a felony assault case from October 1987. Court records show a warrant for second-degree assault remained active for almost 10 years, until it was dismissed for want of prosecution — after the body was found in the lake.

Johnson’s father, now an elderly man, reported that Rodney called him once in the late 1980s, asking for cash, according to the sheriff’s office. Police wonder if it had something to do with legal trouble.

One tip suggested Johnson went camping with a girlfriend and was never seen again, though the timeline of that trip is imprecise.

Detectives are asking anyone who knew Johnson to come forward with information that could help solve the killing. They’re especially interested in anyone who knew his girlfriend, or anything about his camping trips around 1987 or 1988.

At the time the unidentified remains were discovered, it was clear the man had been in the water “for a significant period of time,” according to the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office.

He wore brown work boots, a pair of black socks, a belt with a 1¼-inch-wide buckle, shrink-to-fit Levi’s and a slender pair of Hanes underwear. One of his collarbones had been broken, then healed. He’d been to a dentist for a root canal and fillings. His lower teeth were skinny at the front of his bite, leaving five gaps that would have made for a distinct smile.

All of this was made public over the years in media reports, but tips never led detectives to zero in on Johnson.

An early forensic reconstruction based on the man’s skull showed a face with a dark mullet and a pronounced brow line. It was printed on the seven of hearts in a deck of playing cards that featured local cold cases. The sheriff’s office began giving out decks to prisoners in 2008 with the goal of generating fresh leads. The Lake Stickney man was the only card without an actual name. He was just John Doe. The card described him as “most likely white, but could be Hispanic or of mixed race,” based on an autopsy from the 1990s.

Those conclusions were revised during a renewed effort to find his name in 2016. State forensic anthropologist Dr. Kathy Taylor looked at the skull and determined it had traits often associated with African heritage, or perhaps Asian heritage, or a mix of ethnic backgrounds. A second opinion from Dr. Laura Fulginiti, forensic anthropologist at the Maricopa County Office of the Medical Examiner in Arizona, suggested he was likely white, age 25 to 35.

So forensic artist Natalie Murry took it in all different directions — drawing him as a younger Black man with stubble, then an older Black man with a receding hairline, and last year as a stout Asian man, in a new attempt — with the hope that one reconstruction would be close enough to jog somebody’s memory.

As it turned out, the original findings were almost spot on.

Johnson was about one-eighth Lummi, on his mother’s side. Otherwise, his family came from European immigrants.

Many potential matches to missing persons were ruled out through thousands of hours of research by detective Gregg Rinta. One lead, out of California 2005, caused another Snohomish County sheriff’s detective to send a DNA sample to the University of North Texas, to compare it with that man’s family members. It was another dead end, no apparent match, but it gave investigators a DNA profile that could be uploaded to a national FBI database, CODIS.

Scharf inherited the case in 2008. Dozens more possible matches were ruled out through dental records, DNA and the national missing person database NamUs.

In 2018, Snohomish County death investigators mailed a heel bone, a knee cap, a femur and teeth to an Oklahoma lab, DNA Solutions, to extract a new, more comprehensive genetic profile that could be uploaded to public genealogy websites such as GEDmatch. The same technique was used to catch the suspected Golden State Killer, as well as to crack a growing number of recent cases in Snohomish County.

The lab was able to obtain one-fifth of a nanogram of DNA — that is, one-fifth of a billionth of a gram. About 98% of the sample was bacteria. A typical consumer genetic test, like the kit people often mail back to Ancestry.com, has at least 750 nanograms of DNA.

In this case, the lab was working with about 20 cells, said David Mittelman, of Othram, the Texas lab that sequenced the profile.

“You couldn’t even see it,” Mittelman said. “It’s just a speck.”

In this day and age, it was still enough.

“We weren’t able to identify him until this new tool of genetic genealogy that’s come forward recently, and it’s been a saving grace for a lot of cases,” Scharf said. “So we’re really fortunate that we have the technology now … and that we can identify someone through such a small, minuscule amount of DNA. It’s amazing.”

Othram uploaded the profile to GEDmatch in May 2020.

Ideally, you need a second-cousin match or closer to start building a family tree based on DNA. Jane Jorgensen, a cold case investigator for the Snohomish County medical examiner, saw in GEDmatch that the Lake Stickney Doe had a first cousin living in Anacortes.

Jorgensen has worked with several forensic genealogists on cases in the recent past — and with such a solid head start, she figured she could probably take it from there. In days, she built limbs of the man’s family tree, finding he had dozens of cousins. Then she and Scharf decided to just call up Perry, the cousin on GEDmatch. Perry said she hadn’t heard from two particular relatives in a long time.

One of them Scharf recognized from missing person reports. The man was on a list of possibilities, but he had disappeared way back in the 1980s, in Seattle. Until then, it seemed like a stretch to think he could end up in a lake south of Everett in the middle of 1994.

His name was Rodney.

Spirit Cove

You can trace Johnson’s native lineage in the Pacific Northwest back to the early 1800s. His great-great-grandfather was Thomas She-Kla-Malt, a Lummi man who gave up his tribal rights for a homestead on the far north tip of San Juan Island that is now the site of a family cemetery, Spirit Cove, east of Roche Harbor.

Indian Tom, as he was known to white settlers, died in 1900.

His daughter, Maggie She-Kla-Malt Fitzhugh, had been “born on the property facing Spieden Channel and which has always been her home,” according to her 1943 obituary in the Friday Harbor Journal. The property looks out on the barren southern half of Spieden Island, along a channel known for powerful currents.

Maggie Fitzhugh left behind a daughter, Pearl Little, who was deeded most of the 77-acre waterfront estate on the day before her mother’s death, at the price of “Ten Dollars and Love and Affection in hand paid.” A hearing in front of the Bureau of Indian Affairs later concluded Little inherited the Indian burial ground, too.

Little died with no heirs and no will in 1983.

Claims over who should inherit the land, with an assessed value of over $1 million in the 1980s, gave rise to complex legal questions that reached the state Supreme Court. For example, did a $10 deed bequeathed on a mother’s death bed count as a gift or a purchase?

The She-Kla-Malt lore led Perry to investigate her family’s ancestry and its melding of European and Native American cultures. She took a class at the University of Washington to become a certified genealogist around 2003, she said, and as part of her studies she sent her saliva to a lab for DNA analysis.

It was not until much later that she shared her genetic profile with GEDmatch. Her father’s side has roots in the British Isles, and an Irish heritage group encouraged her to upload her profile this year. It’s a site where people can import genetic tests by different ancestry companies like 23andMe, AncestryDNA and others, in search of relatives.

Debates over privacy and informed consent have sparked controversy in genealogy circles ever since GEDmatch and other DNA banks began allowing police to peruse millions of genetic profiles, without a warrant.

GEDmatch updated policies in light of public criticism of how police used the database, now requiring people to approve police use of their information. Another site, FamilyTreeDNA, branded itself proudly as a tool to not only find long-lost relatives but to help catch criminals. Many users, including Perry, are willing to trust that police won’t abuse the power inherent in their DNA.

Scharf emailed Perry in late May.

“My reaction was, ‘It’s your lucky day, Jim, because I’m going to help you find this,’” Perry said.

She told him what little she knew about Rodney’s family — and how out-of-place that was, since she kept in good contact with almost all of her cousins. In the 1960s, she remembered seeing her aunt, June Johnson, born June Miller, who was Rodney’s mother.

“She came over to where we lived, and she brought her children over,” she said. “It seems to me there were three boys, and they were all little, and that’s about the only thing I knew about the Johnsons.”

A couple of times, Perry’s mother would pass off the phone and tell her to talk with one of the boys — Rodney’s brother.

Rodney’s mother died in 1976. Perry never really got to know the son, and never really knew what became of him.

One of Rodney’s brothers, Christopher, died in Gold Bar in March 2017 when he was electrocuted by walking into a downed, fully charged power line behind the Mountain View Diner.

In May, police tracked down surviving members of Rodney’s family to notify them of their tentative findings about the Lake Stickney case. Samples of the relatives’ DNA confirmed it was Johnson.

The sheriff’s office announced the identity Wednesday at a news conference in downtown Everett.

“It’s many years later than we would have hoped, but we are very glad we’re finally able to identify Rodney and properly return him to his family,” Snohomish County Sheriff Adam Fortney said.

Marianne Lambert is Johnson’s sister, who reported him missing back in the 1990s. She fought tears Wednesday morning as she read a statement to a wall of TV cameras and news reporters.

“Our family wants closure and justice for whoever did this to Rodney,” she said. “His life was snuffed out. He didn’t get a chance to live long, or get married, or have children, or be with his family.”

Johnson’s family plans to bury him in Enumclaw, along with other relatives. To truly put him to rest, detectives are hoping to identify his killer, too, and bring that person to justice.

“Maybe you were too afraid to come forward before,” Scharf said, “but now’s your chance.”

Tips can be directed to the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office at 425-388-3845.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.