EVERETT — The teen arrived in a Chevy Impala. He collapsed near Jason Cockburn’s recovery center, a pale blue house on Colby Avenue. The kid was overdosing on fentanyl.

“We had to Narcan him twice, laying on the couch,” Cockburn said in the meeting hall as coffee pots gurgled.

That was April 9, a Friday. That Monday, a 15-year-old showed up, recently revived from a fentanyl OD. He was looking for help finding addiction treatment — something to help him get off the deadly blue pills flooding the streets here and across the country. The synthetic opioid is 50 times stronger than heroin.

But a frantic scramble to find a detox program for the minor was unsuccessful.

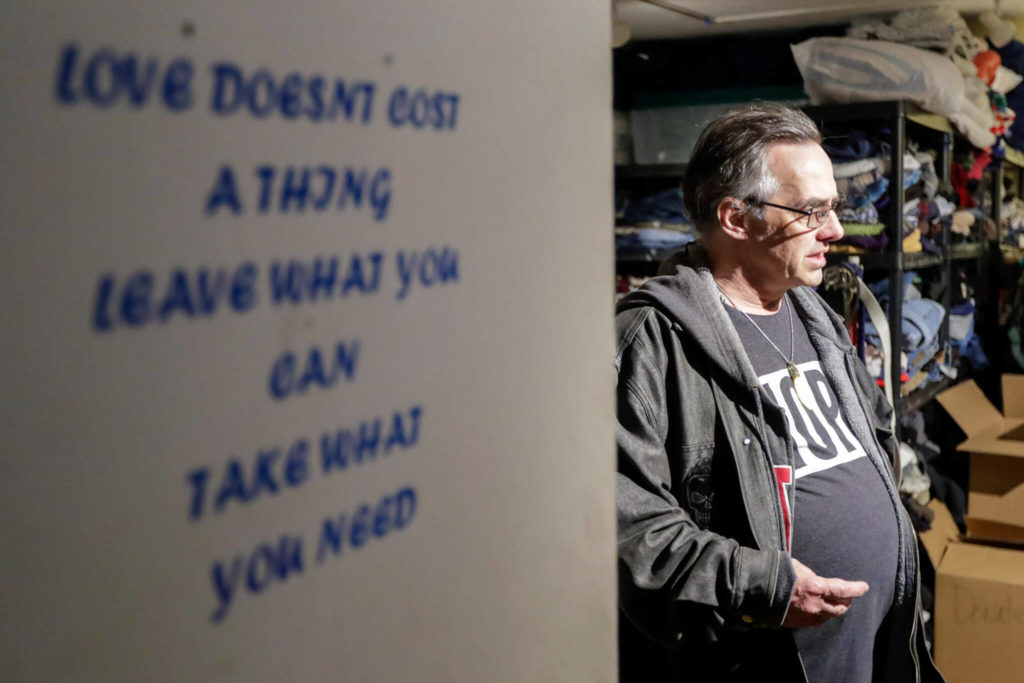

Cockburn called providers, nonprofits and social workers across the state looking for leads. Courage to Change President Mike Kersey lent a hand. So did The Hand Up Project founder Rob Smiley, staff from Everett nonprofit Cocoon House and others.

“It was hours of trying to find a resource for this teenager and just coming up short every time,” said Laura Reed, who volunteers with Cockburn’s Second Chance Foundation.

Smiley asked Facebook friends for help.

“This is the third time in the last 10 days of dealing with a minor trying to detox off of fentanyl,” he said in a video. “And there’s absolutely no place for them to go.”

Recovery from fentanyl can be a grueling battle for adults. For kids, legal questions and a lack of treatment centers accepting youth pose even more barriers. It’s delaying care and keeping kids hooked on the “blues.”

“The 230-pound adult male is taking the same pill the 70-pound kid is,” Cockburn said.

The illicit pills are mixed and pressed in basements and kitchens. One might have a speck of fentanyl, while the next can have a lethal dose.

“The reality is, if we can’t help them today, in the moment, we may not get another chance,” Cockburn said. “They may go out and get a bad pill that night.”

As for the 15-year-old boy who asked for help last month?

With no treatment beds in sight, he was taken to the emergency room, where he was discharged just a few hours later. Any hope for a detox program began to fade.

Two days later, Cockburn paced the sidewalk on Colby Ave.

“The kid was out here smoking blues again when I came in this morning. Same kid. Fifteen years old,” he said, pointing. “He’s across the street now.”

‘Does that actually say 15?’

Wendy Burchill coordinates Snohomish County’s “child death reviews.” Semi-regular meetings focus on either “accidental,” “suicide” or “undetermined” categories.

But this year, for the first time ever, a new category emerged: youth opioid overdose deaths. A special meeting was called in March to analyze those cases. Every accidental overdose was related to fentanyl, Burchill said.

Since 2020, at least 16 teenagers in Snohomish County have died of fentanyl overdose. Six were minors.

“Opioid overdoses in general are increasing. And now we’re seeing youth following the same pattern,” Burchill said. “Some people think we’re putting in a lot of effort into a small number of cases. But again, we’re looking at youth.”

Some evidence suggests overall substance use among children is on the decline countywide.

Over 15,000 students here completed the state’s Healthy Youth Survey last year. The results, in line with state trends, show high schoolers’ opiate use continuing to decline. A March press release about the data heralded “good news about substance use.” Some educators and parents have called the data puzzling, especially considering the trauma and tumult brought on by the pandemic.

Dr. Susan Caverly, who works with addicted teens in Snohomish County, is skeptical of the survey.

“I honestly don’t think we’ve got a full read on how many kids in school are using right now,” she told . “The people responding to that (survey) are actually showing up to class … but the kids I’m worrying about are the kids who aren’t showing up.”

At Ideal Option’s Marysville clinic, Benjamin Rae said he’s often shocked seeing such young patients on his calendar each morning.

“Like, does that actually say 15?” he told the Herald.

Even if fewer kids are turning to drugs, the substance that’s now greeting them on the streets is far deadlier and addictive than before.

Cockburn, at the recovery center, thinks back to when he was a child.

“The problem is the drugs have changed. Before, you might have explored with weed, dabbled in some acid. Your friend might’ve had a line of crank you end up trying,” Cockburn said. “Near-death experiences might’ve taken five years. Reality now is a 15-year-old is picking up a blue, smoking it for the very first time and dying.”

For now, officials and providers are encouraging parents to carry Narcan, the overdose-reversing drug, regardless of whether they think their child is using fentanyl. Fentanyl is often found in other party or study drugs bought off the streets.

Juliet D’Alessandro, a healthy communities specialist at the Snohomish Health District, said her team is looking to ramp up youth-focused awareness campaigns. She pointed to King County’s “Laced & Lethal” campaign as a potential model. The educational campaign also offers free Narcan kits through the mail.

There needs to be “a big flag waving,” she said, with the message: “Hey, we need to really make sure we’re not missing youth with our overdose prevention efforts.”

‘Our youth are paying the price’

Nearly all the teens who stop in at the Cocoon House drop-in center in Everett are struggling with addiction.

CEO Joe Alonzo said two things encourage them to seek treatment: convincing them of the value of their own life and “seeing their friends overdose.”

“I think there’s a real fear they’re going to die,” Alonzo said.

If there were a local detox that took kids, he said, Cocoon House could likely place about one teenager each day. But in reality, the nonprofit is only successful about once a month. Nine times out of ten, Alonzo said, there just isn’t a treatment slot available.

“It’s a tough spot to be in, and our youth are paying the price,” Alonzo said. “What ends up happening is youth get dropped off at local ERs, and the ERs are not equipped. … These young people just kind of bounce around without a real viable treatment option. Usually they’re waiting some pretty significant amounts of time.”

DJ Rivera, a youth clinical supervisor at Catholic Community Services, used to refer clients to a detox in Skagit County. But the facility closed years ago. Now his options are all the way in Spokane and Yakima.

Just up the street, Providence has a 14-bed detox. But teens who present at the emergency room are turned away from that inpatient program. It’s not licensed to treat anyone under 18.

Providence addiction specialist Dr. Todd Carran said his department doesn’t typically refer those kids elsewhere.

“Let’s see,” Carran said over the phone, racking his brain. “What else is there? Wow. There’s not much in this area. There’s very little in this area.”

Providence isn’t looking to open its detox to minors, he added.

“There aren’t a lot of providers trained to treat adolescents,” Carran said. “There’s a limited number of people who specialize in this field. And there’s a lot of people with addiction right now. So I think we kind of got overwhelmed with an increase of individuals using during the pandemic.”

The county’s recent review of child overdose deaths showed many of them sought medical attention for their addiction, Burchill said. That includes going to the ER. Now, Burchill’s team is trying to figure out why those interventions didn’t work.

“Do they just show up at the ER and then they’re treated and released with no resources? We just don’t know,” she said. “Why weren’t they admitted or referred to inpatient care?”

Yet another barrier Cocoon House runs into while looking for services: Some centers who accept teens insist on parental consent. That’s not always easy for kids who are homeless, on the run from abuse or no longer in contact with their guardians.

Under state law, kids 13 and up can submit to inpatient treatment for substance use disorder without parental consent. But the law, Alonzo said, is “a little bit up to interpretation.” That’s because the state also compels shelters to contact guardians within 72 hours.

Cocoon House staff push back if immediate treatment is needed and the child’s parents can’t be reached.

“We say to them, ‘Hey, you’re not a housing provider. You’re a treatment provider. Youth can consent to medical treatment at 13,’” Alonzo said. “We’ll go to battle with that youth for that placement, wherever we can. … It doesn’t sound like we have success every time.”

It’s “an extreme gray area,” Ideal Option’s April Provost said. “And most people would rather err on the side of caution.”

The clinic prefers to send clients to inpatient detox first. There, professionals can monitor the often-grueling and drawn-out withdrawal symptoms that come with discontinuing fentanyl.

But with so few options for teens, they’re often asked to wean off fentanyl on their own while the clinic slowly increases their Suboxone intake. The medication blunts cravings and eases withdrawal discomfort. Ideal Option staff said the more hands-off approach isn’t ideal.

For Cockburn, at the recovery center, it’s infuriating to see kids denied treatment if a parent isn’t around. Kids can consent to emergency medical services if no guardian is readily available, he noted. Considering how deadly fentanyl is, he said, detox and addiction programs should be treated the same.

“It breaks my heart when I try and fail, and see the same kid sitting here the next day doing the same thing,” he said. “Why do we need permission to save a life?”

Claudia Yaw: 425-339-3449; claudia.yaw@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @yawclaudia.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.