Beneath steep slope, Concrete neighbors fear landslides from logging above

Published 6:30 am Saturday, July 6, 2024

CONCRETE — A hillside rises 1,300 feet within less than a mile, right behind 83 homes known as Sauk River Estates.

If a logging company carries out its plans to cut 54 acres on this steep slope this summer, residents fear their neighborhood could become another Steelhead Haven, where 43 people died in the devastating Oso landslide in 2014. Sauk River Estates is only 26 miles away from remnants of the 650-foot-tall hill in Oso, along Highway 530 — and 10 miles away from Snohomish County lines.

It is hard to say if landslides have ravaged near this Concrete community before, as they did around Oso decades before the tragedy. State geologists haven’t mapped historic landslides in Skagit County yet.

In Sauk River Estates, bigleaf maples, Western redcedars and Douglas firs shade a stretch of homes and trailers along a single gravel road called Mountain View Lane, bordered with bleeding hearts, nettle and salmonberries.

Other than the rumble of an occasional car driving past, the community felt peaceful and still on a sunny morning in late June. The clear blue Sauk River rushed by in the near distance.

Resident Kim Skarda only learned about the nearby logging project this spring, when a neighbor noticed workers from Nielsen Brothers marking trees with orange and pink flagging tape. She lives and works on Orcas Island, visiting her trailer parked at Sauk River Estates at least once a month.

“If you see anybody out there flagging or on the property,” Skarda said to her neighbor, “ask for their card.”

And sure enough, a forester with the logging company, Sam Petska, gave Skarda’s neighbor his card. Only then did Skarda discover the Bellingham-based logging company already had permits to start cutting for its “Hokanson” project, with approval from a state Department of Natural Resources forester.

Petska obtained these permits, residents said, without consulting anyone who lives nearby.

On June 3, the Sauk River Estates Board appealed the project with the state’s Pollution Control Hearings Board.

“We believe the report from Samuel Petska includes factual inaccuracies and is a misrepresentation of the area in the permits,” the board wrote. “He failed to mention in his report there is an entire community below the property to be logged.”

They continued: “We are requesting that Nielsen Brothers Logging cease any and all conduct aimed at disrupting or harming the residents of Sauk River Estates until a licensed geotechnical engineer can assure all parties that we are not facing another Oso incident.”

Petska did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Daily Herald.

‘Potentially unstable terrain’

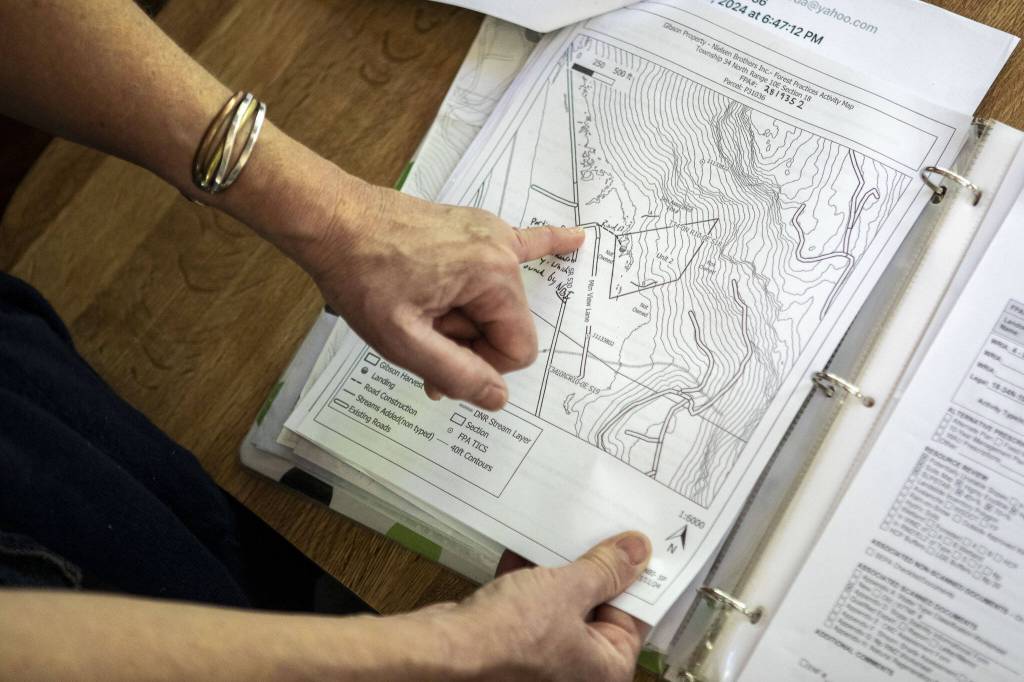

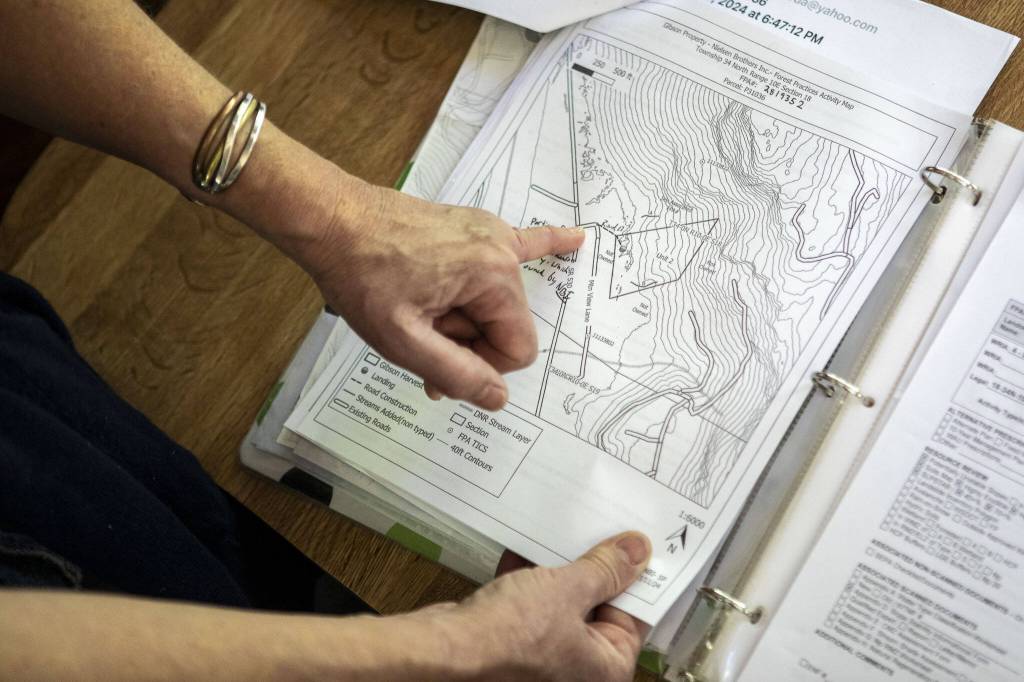

Skarda spent weeks sifting through Nielsen Brothers’ permits and consulting lawyers, as well as other experts, to learn more about the application for the project.

“When I first heard this was gonna happen, I got pretty upset,” Skarda said. “It was like something threatening something that is important to me — something that I love deeply. I realized how much I do love this place, and this forest, and this water and these people. I was so depressed. And then it got to a point where I was like, ‘I have to take action. I have no choice.’”

She hopes Nielsen Brothers will reevaluate the classification of the logging to note its potential danger to the environment and public safety. Tree roots anchor soil. When timber is logged, the ground loosens.

“Class I” and “Class II” permits describe situations with few to no public or environmental threats.

Petska, forester for the company, labeled the logging permits as “Class III” — meaning forest practices that have “an ordinary potential to damage a public resource,” according to the Governor’s Office for Regulatory Innovation and Assistance.

One step further, “Class IV special” permits describe forest practices with “potential for a substantial impact on the environment.”

Alex Gray, the Sauk River Estates’ president, hired geologists with Aspect Consulting in Seattle to assess the stability of the slope remotely. The geologists evaluated aerial photographs, landslide mapping and geologic surveys, identifying “multiple areas of potentially unstable terrain” not addressed in the logging company’s permits, according to the report.

The geologists also found evidence of a potential landslide inside the section Nielsen Brothers planned to log, by looking at lidar data. After the 2014 Oso landslide, geologists used this same aerial mapping technology, which stands for “light detection and ranging,” to discover that at least 25 major landslides scarred the Stillaguamish River valley prior to the slope’s collapse.

Staff with Aspect Consulting recommended Nielsen Brothers hire an expert to assess the potentially unstable features in person.

Aspect Consulting geologists also noted that a hired expert should address potential threats to Sauk River Estates residents and harm to the community’s drinking water.

“The report should include analysis and figures and be stamped by a licensed engineering geologist listed on the DNR-qualified expert list,” Aspect Consulting’s assessment states, “and provide justification that a Class III permit is appropriate” — not a Class IV special.

The slope assessment will cost Sauk River Estates up to $8,000

“This neighborhood’s worth it to me,” Gray said, ”certainly my own livelihood as well.”

Nielsen Brothers representatives told those involved with the case that they planned to consult their own geologist, shortly after the Sauk River Estates Board shared the report.

Last month, Gray called Kirsten Rowley, a resource protection forester with the state Department of Natural Resources, to point out the inaccuracies with the permits she approved.

Rowley supported the validity of the permits, Gray said, even when he told her Sauk River Estates residents were never consulted about the logging project.

DNR cannot comment on private sales, spokesperson Ryan Rodruck said.

In general, DNR officials will approve any timber sale if the forester completing the permit has the necessary qualifications, and filled out the application correctly, Rodruck said.

‘I hope we have witnesses’

A decade ago, the Oso landslide engulfed the Steelhead Haven neighborhood in 19 million tons of sand, clay and timber.

It is still unclear if timber sales starting in 1933 and continuing into the early 2000s in the Stillaguamish River valley loosened the hillside, placing those who lived below in danger.

Just days after the slide, some locals had insinuated nearby logging could have played a role in causing the slide. In 2016, victims’ families reached a $10 million settlement with the Grandy Lake Forest Associates timber company.

But geologists who studied the tragedy near Oso noted massive landslides flooded the valley long before commercial logging started in the region, according to lidar data.

This week, the Sauk River Estates Board hired a lawyer to represent them in the case.

“We have to try to find some help,” said Marjorie Sorenson, secretary and treasurer for the board. “We tried to be our own lawyers, and we kind of found out that we were in over our head.”

For a community with limited resources, Sorenson said the case is daunting: a small group of residents versus the state Department of Natural Resources and a logging company.

Sorenson and other neighbors worry Nielsen Brothers staff would damage Sauk River Estates’ aquifer, as the loggers trek vehicles and heavy equipment back and forth over the neighborhood’s easement road.

“They could ruin the ground there, which is unstable, and they could ruin our water source — everybody’s water,” she said.

By July 17, Nielsen Brothers representatives need to respond to the maps and reports submitted by the Sauk River Estates Board. The Board has has until July 31 to reply.

Even with the board’s appeal, Nielsen Brothers staff can still log the parcels above Sauk River Estates, with three days notice.

“Technically, because they have the permits, they can go anytime they want,” Gray said. “As the judge stated in our last meeting, if they decided to do that, the whole argument becomes kind of moot.”

And from a financial standpoint, Gray said the board will have exhausted all of its resources.

“I can’t take the HOA into debt,” he said. “We’d have to throw our hands up and say, ‘OK, well, it’s all over for us.’”

Residents would then have to seriously consider the risks of continuing life in Sauk River Estates.

Neighbors who want to move may struggle to find newcomers willing to live under the threat of a steep slope that was recently logged.

The Sauk River Estates Board plans to hold an informational meeting for residents to discuss the logging project and how it could potentially devastate the community.

“I hope we have witnesses,” Skarda said while walking around the neighborhood in late June. “I have to … bring as many people to the awareness of it happening and how it’s happening and why it’s happening in order to shine the light on the the practices that are in place that are allowing this.”

Ta’Leah Van Sistine: 425-339-3460; taleah.vansistine@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @TaLeahRoseV.