EVERETT — Imagine a place so popular that every morning brings about 40 more people than the day before, each one intent on finding a place to squeeze inside.

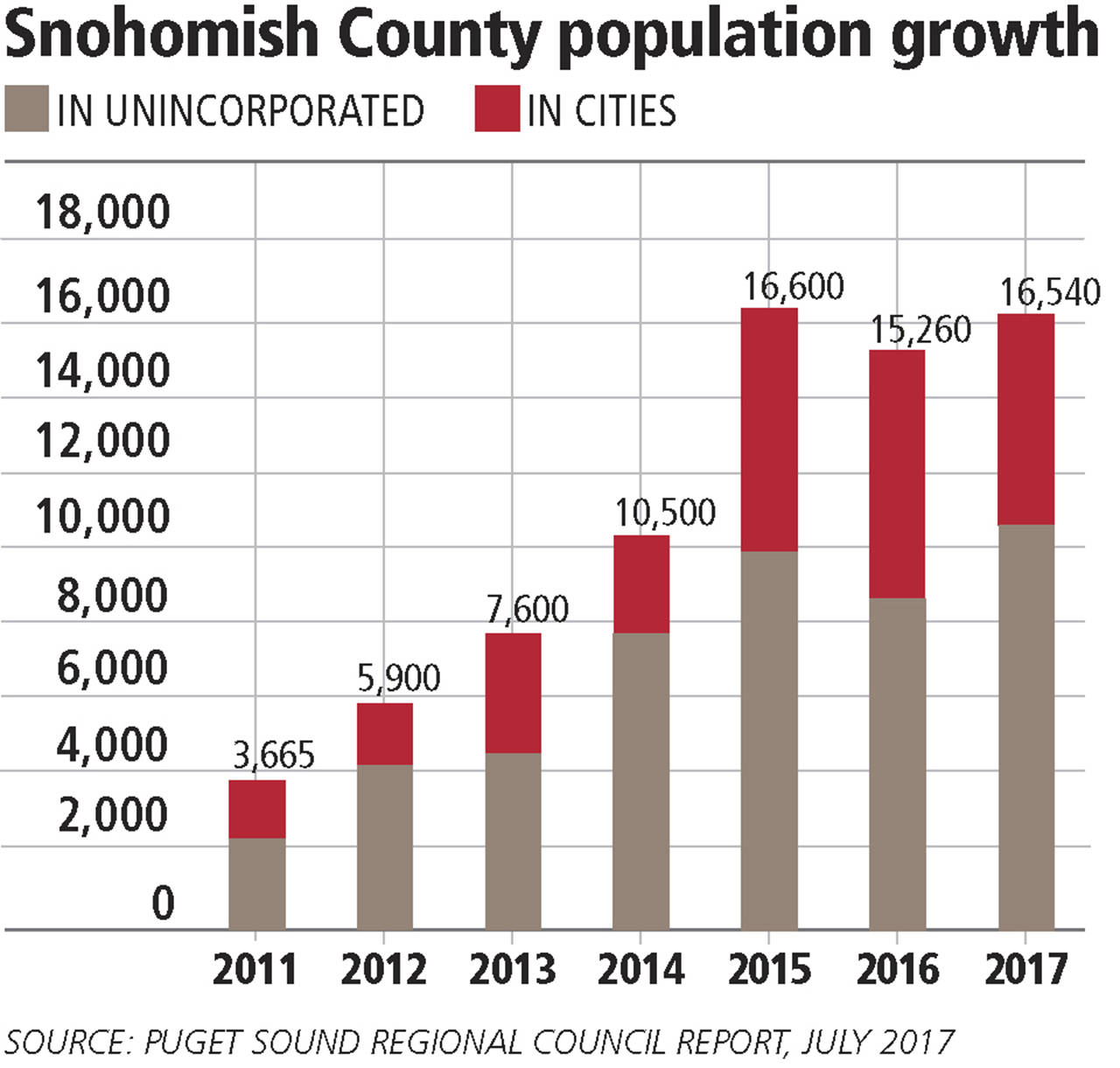

The numbers add up fast: roughly 300 a week, more than 16,000 a year. That’s the equivalent of a small city of newcomers, enough to easily fill every seat in Xfinity Arena for an Everett Silvertips playoff hockey game — twice over.

This has been the unexpectedly rapid pace of growth in Snohomish County the past three years, according to data released early this month by the Puget Sound Regional Council.

Since emerging from the doldrums of the recession in 2014, the county’s population has swelled by more than 48,000 people and now hovers around 790,000 and counting.

Six in every 10 of those newcomers landed in the county’s unincorporated areas, particularly around Bothell, North Creek, Lake Stevens and Marysville. Among cities, Everett added the most new residents in the past three years, 4,900, followed by Marysville (3,300) and Lake Stevens (2,570).

Not only is population growing faster than county and city leaders anticipated. Most of those new folks are not settling in locations where county officials hoped they would.

The comprehensive plan adopted by the Snohomish County Council in 2015 estimates how many more people will move into each city, and unincorporated areas near them, in the next two decades. It predicts the county population will grow by 200,000 by 2035 and the majority of the new arrivals will settle in a city.

Just the opposite has been occurring. Population has risen faster in unincorporated areas than cities in each of the past seven years, data show. Of the 76,065 new county residents since 2010, 47,508 found a home in an unincorporated area compared to 28,557 who now live in a city.

“We tried to encourage more growth in our urban areas,” said Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers, a former county councilman. “When we pick a number it’s not what we’re allowing or allocating. It is a prediction. It is a planning target. What happens in reality is not what you’ll necessarily get.”

Mike Pattison isn’t surprised at what Snohomish County is experiencing. He cautioned county council members to not ignore the marketplace in the course of its hearings on the comprehensive plan.

“The amount and location of growth we’re seeing is exactly what we’ve been seeing for some time now,” Pattison, the government affairs manager for the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties, said Friday.

Consumers desire single-family homes and the one place in the region where they’re getting built is in Snohomish County, and in particular its south end, he said.

“Buyers are willing to drive until they find them and the first place they’re finding them is south Snohomish County,” he said.

More on the way

Snohomish County isn’t the only place getting more crowded.

The regional council noted the central Puget Sound region — Snohomish, King, Pierce and Kitsap counties — is now home to more than 4 million people.

King County leads the way with 2,153,700 followed by Pierce County with 859,400, Snohomish County with 789,400 and Kitsap County at 264,300. Snohomish County grew 2.1 percent this past year, second only to King County at 2.3 percent.

Everett, at nearly 110,000 people, is the region’s fifth most-populous city. Marysville, at nearly 66,000 residents, is the county’s second most-populous place. It now rounds out the region’s top 10. Bothell, Edmonds and Lynnwood are in the next tier for the region.

In terms of new residents, Everett added the most of any city in Snohomish County since 2010. Everett gained 6,781 followed by Marysville with 5,880, according to the data.

But the population in Lake Stevens grew by the largest percentage of any city in the county, in part due to annexations. Lake Stevens added 3,671 residents representing a 13 percent boost. Marysville and Snohomish both recorded 10 percent growth with 5,880 and 912 more residents, respectively.

Meanwhile, population in the unincorporated area has experienced a 16 percent growth since 2010.

Making it work

A failure to foresee the housing boom in south Snohomish County is why infrastructure in that area — especially the transportation grid — is overwhelmed. New services, resources and road improvements envisioned in the comprehensive plan are tied to the assumption that population growth will occur mostly in the cities.

Democratic state Sen. Guy Palumbo lives in Maltby — which is near the epicenter of south county’s recent surge. One reason he ran for office is to find state funds to help the area deal with the negative effects.

“We do want to have growth in the Urban Growth Area,” said Palumbo, a former Snohomish County planning commissioner. “The problem is it is not going into the cities, it is going into the county.”

He said the update of the comprehensive plan in 2005 also sought to steer new growth to cities. It didn’t succeed either and failed to help one of the fastest-growing areas of the county prepare.

“We didn’t plan for the growth that has come here. We have to be more nimble in our planning procedures when the reality of what is happening on the ground does not match what was in a planning document from 10 years ago,” he said.

Growth means different things in different places.

Edmonds Mayor Dave Earling oversees “a community that, in essence, seems to be pretty well built out.”

As planners in this city of 41,000 figure out where to accommodate thousands more, they’ll be looking toward the city’s approximately 2-mile stretch of Highway 99 and other busy thoroughfares.

“Highway 99 will be a critical piece for us,” Earling said. “We see that as an area where we can expand affordable housing.”

Somers said Friday it may be time for the county and cities to revisit the population targets on which the comprehensive plan is based. He said he’ll bring it up at a meeting next month of Snohomish County Tomorrow, a collaboration of cities and the county.

“It’s not real concerning to me,” he said. “But we’re coming in hot right now so do we need to make adjustments or do we let it play out. There is not a spigot with a handle that you can turn growth on and off. It happens to you and you plan it for as best you can.”

Reporter Noah Haglund contributed to this story.

Jerry Cornfield: 360-352-8623; jcornfield@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @dospueblos.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.