MONROE — Seven months after a nurse found a lump in his chest, an inmate at the Monroe prison wrote a note to the only people who could help him.

“I do not have long to live according to an outside specialist who is the fourth leading cancer doctor in the world,” the man wrote in fall 2018. “He told me I need to start chemo aggressively right away or would not live nine months. This was 2 months ago. What is taking so long?”

The man died in June 2019. For more than a year, he’d received no real treatment for his cancer, according to findings released Monday by the state Office of the Corrections Ombuds.

The man was due for release six months after the date of his eventual death, with time off for good behavior. His passing has led to reforms in how medical issues are handled and documented at the Monroe Correctional Complex.

The findings come months after The Seattle Times first reported the head doctor at the prison, Dr. Julia Barnett, “failed to advocate for these patients and delayed emergency medical care, which was essential to life and caused significant deteriorations in patients’ medical conditions,” according to a Department of Corrections investigation.

Management found Dr. Barnett appeared to make decisions “to reduce health care costs rather than for the benefit of the patient or for the benefit of the staff,” leading to inadequate care for at least six inmates, including three who died.

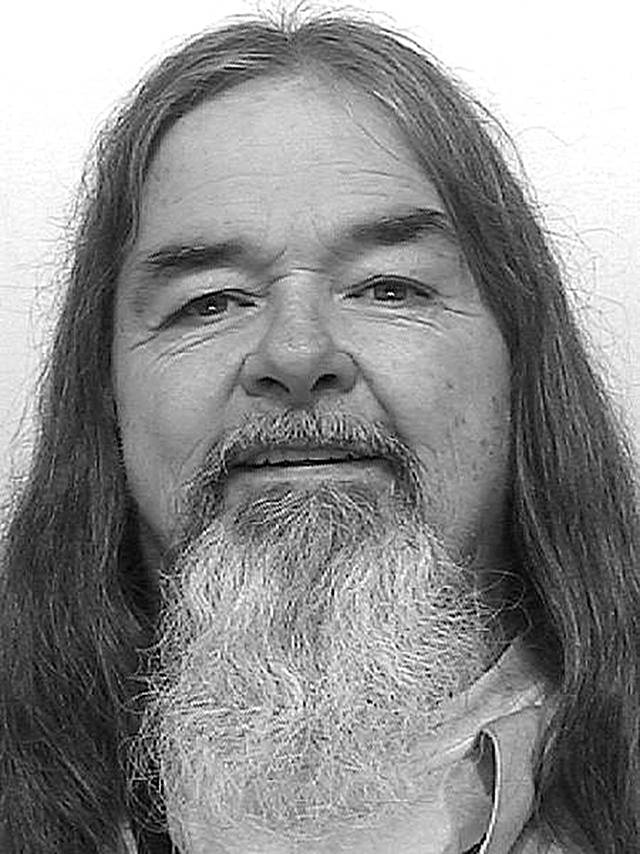

The new report released Monday did not name the deceased man. A spokeswoman for state Corrections said she was unable to confirm his identity. Snohomish County death records, however, show he was Kenneth Wayne Williams, 63, of Kent. He’d been found guilty of two counts of second-degree assault for hitting his girlfriend and shooting her son at a condominium in early 2015.

Williams was sentenced to seven years behind bars in 2016.

Less than two years later, in March 2018, the inmate began feeling ill, and a registered nurse found a lump on his chest. Supervising staff members in the prison were notified, but they “took no action,” according to the report completed by assistant ombuds Matthias Gydé.

After two months, the inmate wrote a note: “I need to see a provider. I have signed up 5 times, wrote one kite (a message to prison staff), went to sick call where the nurse felt the lump in my breast and told that I would surely see a provider but still nothing on the call outs. … I feel I have been very patient, can you help me please. Thank you.”

Four months had gone by when the man saw a physician assistant, who saw an urgent need for a mammography and ultrasound. But it took “another month for these ‘urgent’ needs to be satisfied,” the report says.

A biopsy in August 2018 revealed invasive carcinoma.

Thirteen days passed.

Then during an unrelated trip to the medical ward, staff noted he hadn’t been informed of his cancer diagnosis. He was told about it then. A treatment plan was set up: genetic counseling, a staging workup, port-placement, surgical and radiation consultation with an oncologist, CT scans, a brain MRI, and chemotherapy — “as soon as possible.” Only the staging, a CT scan and a bone scan were ever completed, according to the investigation.

“The oncologist told me on Aug. 22nd, 2018 that I needed to start aggressive chemotherapy ASAP and said he would schedule me for the following week,” the inmate wrote in his seventh month of waiting for treatment. “This was now seven weeks ago, almost two months and I have not been given any reasons for the delay. I am dying, what is holding up my treatment that will save my life?”

The following month, the man signed a “do not resuscitate order.” He had requested comfort measures only, when he died this year of metastatic breast cancer.

In the complaints quoted above, the man’s grievances were returned to him to be rewritten, for reasons that aren’t made clear in the report. After they were not resubmitted in seven days, the grievance was automatically withdrawn.

Reports show that Corrections medical staff gave “varied” or uninformed answers about what to do for notifying a health provider after hours or on weekends; what actions to take when they found a suspicious lump or lesion; or how to make followup appointments.

“There does not appear to be any system in place whereby the reviewing provider actually makes a note that they have received, reviewed, or acted upon the orders,” Gydé wrote. “In fact, at least two staff members interviewed state that they are often asked to initial something and they do so as a matter of routine, … but they do not necessarily read and or respond to what they are signing.”

It turned out staff was not able to look at reports from outside providers, except to see that they had been signed.

The report gave a series of nine recommendations to learn from this case: a new, clear policy on following up on reports of lumps and lesions; a clear policy on how to handle urgent medical requests, with a timeline; a clear policy on how to notify a patient of a diagnosis in a timely manner; a better system for documenting every interaction with a patient; extensive retraining; and other fixes.

The Monroe prison has a plan to follow through on all of those recommendations by spring, according to a response written by Steve Sinclair, secretary of state Corrections. Some of the issues have already been addressed, with reminders sent out to staff Friday.

Janelle Guthrie, the agency’s director of communications, released a statement Monday: “Department of Corrections health services staff care deeply about providing high quality care to incarcerated individuals. Following an internal review of this tragic situation, the Department identified and is implementing significant process changes to address failures identified in the review. Those process changes are outlined in the Department’s response to the Ombuds report. The Department of Corrections remains committed to operating a safe and humane corrections system, and to continually improving how we care for individuals in state custody.”

Since the systemic breakdown came to light in this case, the man’s primary care provider has resigned, Guthrie said.

The prison’s former head doctor, Barnett, was fired in April.

Anyone who wishes to make a report to the state Corrections Ombuds — the office that investigated this case — is welcome to call 360-664-4749.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.