EDMONDS — It started with jaywalking, an offense a sheriff’s office investigator would later call “the most minor pedestrian traffic infraction.”

What followed for Sharon Wilson, then 25, was a tackle by a sheriff’s deputy, a traumatizing night in jail, a public uproar and a civil claim against Snohomish County that ended in a $75,000 settlement this month.

In March, Wilson, who is Black, sued the sheriff’s office in federal court, claiming she was running to catch the bus after a shift as a certified nursing assistant when sheriff’s deputy Matt Lease tackled her for no reason three years prior.

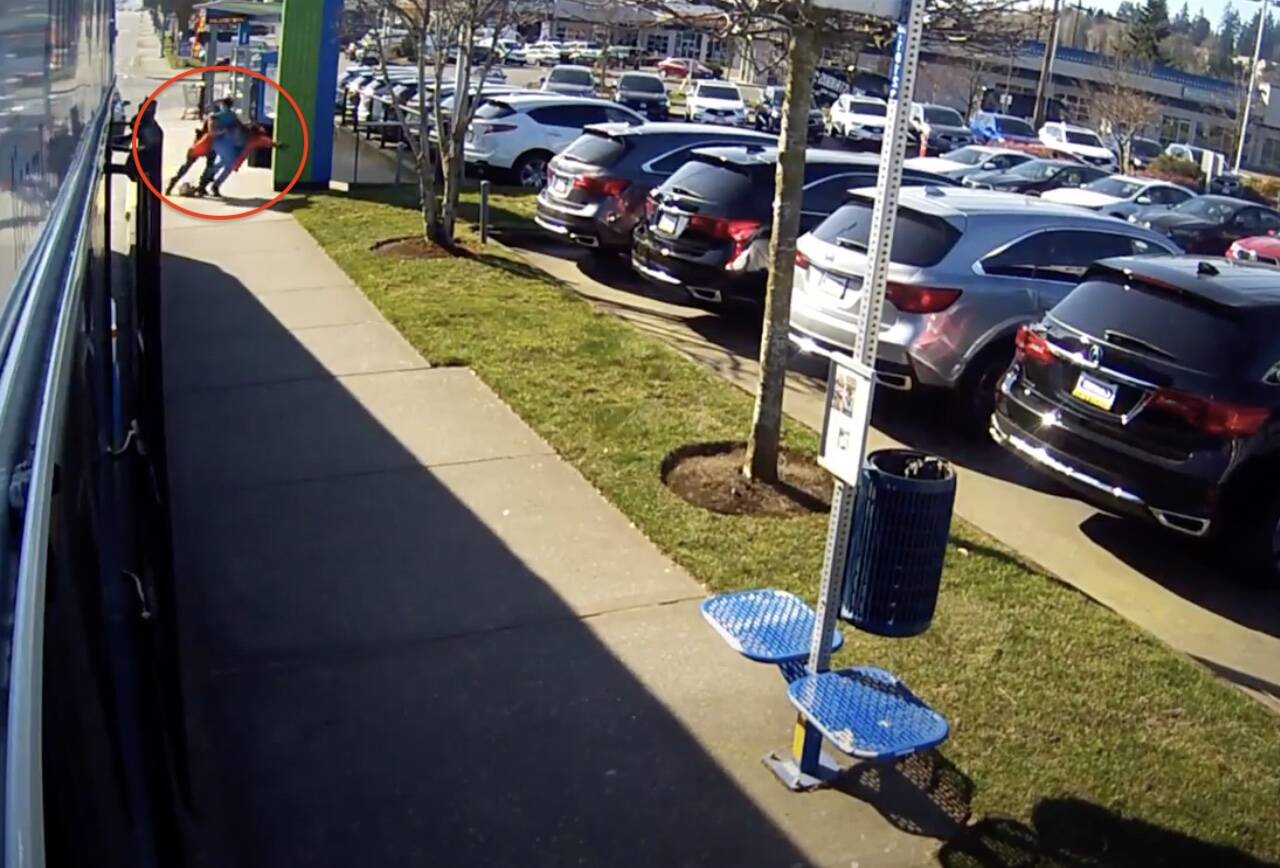

Records and surveillance footage from the scene obtained by The Daily Herald paint a more complicated picture of the March 2020 episode that resulted in Wilson’s arrest for investigation of resisting arrest and obstructing law enforcement.

Sheriff’s office spokesperson Courtney O’Keefe deferred to the county prosecutor’s office for comment Monday.

Bridget Casey, the county’s chief civil deputy prosecutor, noted in an email that “the County defendants admit no liability as acknowledged by the settlement agreement and resolved this matter for a nominal amount.”

The Seattle Times first reported the settlement Monday.

Then-Snohomish County Prosecutor Adam Cornell asked his counterpart in Whatcom County, Eric Richey, to review the allegations against Wilson at the time.

Richey declined to file the resisting arrest and obstructing law enforcement charges against Wilson. He acknowledged probable cause existed for the charges. But writing just weeks after police killed George Floyd in Minnesota, he noted there could be issues proving the case to a jury.

“Following the death of George Floyd, and the subsequent public reaction,” Richey wrote, “it would be unlikely that a jury would consider it appropriate for a law enforcement officer to tackle a jaywalker just to check her for warrants, especially where the subject is a person of color.”

His decision made no judgment on how authorities treated Wilson.

Wilson’s arrest was used as evidence in one of the failed recalls of Sheriff Adam Fortney, as petitioners claimed the elected sheriff failed to investigate the case before taking to social media to defend Lease’s actions, amid an uproar over the force used against a Black woman working as a nursing assistant in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Describing the sheriff’s quick response, defense attorney Samantha Sommerman said in an interview earlier this year that Fortney has a “knee-jerk reaction to defend police in any circumstance.”

Sommerman, one of the leaders of the recall effort, raised the question of whether this would’ve happened had Wilson been white.

Wilson’s lawsuit argued the sheriff’s office discriminated against her because of her skin color.

A sheriff’s office investigation found deputy Lease followed internal policy on biased policing and use of force. Wilson was not interviewed as part of the inquiry, despite attempts to reach her.

Wilson was represented by the Bellevue-based James Bible Law Group. Bible has represented the families of Manuel Ellis, who was killed by Tacoma police the same month, and Tirhas Tesfatsion, who died by suicide in the Lynnwood Jail in 2021.

Wilson’s attorneys didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The tackle

On the afternoon of March 21, 2020, Wilson ran to catch a Community Transit bus after finishing a shift as a certified nursing assistant at the dawn of the pandemic.

In her version of events, laid out in the lawsuit filed in March in U.S. District Court in Seattle, she was listening to music on her headphones. But before she could hop on, Lease tackled her.

In the sheriff’s office version, Lease, a deputy with the Transit Police Unit, had stopped Wilson after seeing her jaywalk across Highway 99 at the intersection of 216th Street SW. In his report, Lease wrote Wilson walked in the crosswalk, but didn’t have a signal to walk. Despite having a green light, Lease and another car had to slow down to allow Wilson to pass.

Lease told Wilson to sit on the bus stop bench, where he added she wasn’t free to leave, according to a sheriff’s office investigation.

Wilson told the deputy she needed to catch the bus because her grandmother was in the hospital. While this happened, the bus approached, as Lease reported later in the investigation interview. Lease advised Wilson another bus would come in 20 minutes. He reported offering to drive her wherever she needed to go, but that he wanted to verify her identity first.

The next few moments were caught on security footage from the bus.

The bus pulls around Lease’s patrol car, with its lights flashing in the bus lane, the video shows.

“Can I please get on my bus?” Wilson pleads with Lease.

As the bus stops, Lease stands over her. Wilson gets up from the bench and runs.

“(Expletive) you, don’t touch me,” Wilson tells Lease.

She screams as Lease pushes her down into the grass next to the stop, just steps from where she’d tried to run. The deputy holds her down with his knee as the bus leaves the stop.

After the bus left, passengers wondered what happened. A man who had just gotten on explained Wilson had crossed the street “while the light was red because she was trying to catch the bus, and he’s giving her a hard time.”

Lease called for backup and handcuffed her after a struggle for her wrists, he told sheriff’s office investigator Lt. David Bowman. Lease’s supervisor, a fellow deputy, an Edmonds officer and paramedics responded.

In the lawsuit, Wilson reported Lease was on “top of her, yelling accusations at her that she had not obeyed his commands.”

“Ms. Wilson tried to explain that she had not heard any commands because she was wearing headphones and could not hear over her music,” the complaint reads.

The lawsuit says Wilson felt an “agonizing amount of pain” from the tackle due to sickle-cell disease that makes her hypersensitive to contact. She declined aid from paramedics, according to the internal inquiry.

Wilson was hyperventilating, so the Edmonds officer gave her an inhaler.

Wilson also reported asking for a woman to frisk her, instead of Lease. He continued anyway, at DeWitt’s instruction, “making her feel further violated and harassed,” the lawsuit says.

The other deputy on scene, Blake Iverson, later told his supervisor he wasn’t “super comfortable with the level of force as far as tackling somebody over jaywalking,” according to Bowman’s investigation.

After their interview, Bowman showed Iverson the security video of the tackle. After watching, he changed course, reporting “that’s exactly what I would have done.”

Lease’s supervisor, Sgt. Glenn DeWitt, also felt the deputy acted appropriately.

“It sounds like you did everything right and I would have done the same,” DeWitt reportedly told Lease. “In your situation … I have done the same.”

After seeing the video, a sheriff’s office instructor also told Bowman the use of force seemed reasonable.

Bowman’s investigation found Lease didn’t violate sheriff’s office use of force policy. He wrote “this use of force was minimal to gain control of Wilson.”

The jail

Just weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, heavy booking restrictions were in place at the Snohomish County Jail.

Specifically, the jail accepted far fewer suspects accused of nonviolent and misdemeanor charges. Over two weeks in March 2020, the jail population dropped at least 30%.

While Lease detained Wilson at the bus stop, his fellow deputy, Iverson, asked what the plan was. Lease told his colleague he was going to book her into jail.

Iverson expressed concerns, according to the sheriff’s office inquiry.

He later told Bowman, the sheriff’s office investigator, “we were at the height of our COVID pandemic, we had some pretty strict jail restrictions,” records show. He noticed Wilson was wearing scrubs, indicating she may have been working in a hospital or adult family home where she could’ve been exposed. And not long before the arrest, agency leadership had ordered staff to “curtail/limit proactive criminal enforcement given our current environment.”

DeWitt, the sergeant, described Lease as one of his most proactive deputies. DeWitt was also named as a defendant in Wilson’s lawsuit.

Lease reiterated to his colleague that Wilson was going to jail. Iverson encouraged Lease to call the jail to confirm they’d accept her, according to sheriff’s office records.

“If I had to use force, she’s going,” Lease reportedly responded. “If they have a problem with that, we’ll deal with that later.”

Wilson argued in her lawsuit that being immunocompromised was another reason she shouldn’t have gone to jail.

Lease planned to arrest Wilson only for investigation of obstructing law enforcement, DeWitt, his supervisor, told Bowman. But DeWitt overrode Lease, directing him to add a resisting arrest allegation based on the struggle to get Wilson into custody.

On the way to jail in Lease’s patrol car, Wilson called him a racist, the deputy reported. In an interview with Bowman, his supervisor said Lease didn’t disproportionately stop people of color.

Sheriff’s office policy required all employees to attend racial profiling training. Lease believed he had participated. Training records reviewed by Bowman didn’t appear to show he’d attended, however.

The policy at the time defined racial profiling as “the practice of detaining a person based on a broad set of criteria which casts suspicion on an entire class of people without any individualized suspicion of the particular person being stopped.”

Bowman determined “that is clearly not the case in this incident, both from the information from Dep. Lease seeing a violation on the road and a witness recorded on the coach talking independently about the observed violation.”

Wilson spent that night in jail. At one point, Lease visited her while she was in custody, according to the lawsuit. The deputy told her it was all a “misunderstanding,” she reported. He hoped she “learned” from what happened.

Meanwhile, the arrest meant she was banned from riding Community Transit buses. Community Transit later lifted that ban, however.

The aftermath

Five days after the tackle, Wilson’s lawyer took to Facebook.

“WE WILL NOT BE SILENT ABOUT POLICE MISCONDUCT,” James Bible’s post began.

Bible called on the public to do a few things. He wanted them to tell the prosecutor’s office to decline to file charges and tell the sheriff’s office to “stop covering up wrong doing.”

“Please spread this story far and wide,” the lawyer ended the Facebook post.

Some community members answered the call to action. One emailed the sheriff’s office that “this was a ridiculous and hateful attack.” Another called for an immediate public apology. Yet another wrote she was “tired of hearing stories like this happening to African American members of our community.”

The day after Bible’s post, Fortney penned a lengthy one of his own. He rebuked the public narrative, arguing Wilson broke the law when she crossed Highway 99, leading to Lease’s stop. He repeatedly mentioned Wilson didn’t comply with Lease.

“While this entire incident is unfortunate, it is unfortunate because of the actions of Ms. Wilson,” wrote Fortney, who took office a couple months earlier. “It would simply be unreasonable to have an expectation of law enforcement to simply watch people who decide to suddenly get up and run from the police and watch them run away.”

That same day, then-operations bureau chief at the sheriff’s office Ian Huri, who is now the undersheriff, asked Bowman to look into the case, despite the complaints seemingly being “based on opinion instead of fact,” Huri wrote.

Bowman, the lieutenant who later investigated the case at the sheriff’s office, wrote in an email to Huri: “I do not believe there is anything to look into.” His inquiry later cleared Lease of any policy violations.

In May 2020, a group of four local attorneys behind a recall effort cited the Wilson episode as an example of Fortney’s mismanagement of the sheriff’s office. They argued he needed to authorize an internal inquiry following Bible’s post.

“Instead, Sheriff Fortney continued his pattern to defend his deputies against any and all allegations of misconduct in the apparent belief that his deputies are incapable of misconduct,” the recall reads.

In a written response filed in court, Fortney said his social media statement was “entirely informed and driven by a desire to get accurate information to the public.” He noted the post didn’t indicate he was clearing Lease of wrongdoing.

In June, a San Juan County Superior Court judge found this allegation legally sufficient to be included in the recall. But on appeal, state Supreme Court justices tossed the charge from the recall.

“Though the petitioners allege Fortney failed to perform his duty to properly investigate a complaint, they have not provided the complaint for review,” Justice Mary Yu wrote. “There is no record that provides the necessary details. Without this information the petitioners have failed to show ‘identifiable facts’ to support their allegations and assess Fortney’s actions.”

The recall failed after the attorneys failed to turn in the signed petitions needed to put the recall question to voters.

The settlement in the Wilson case comes as Snohomish County voters decide whether to keep Fortney as sheriff for four more years, as he faces a challenge from a former colleague, Susanna Johnson, now the deputy police chief in Bothell.

Jake Goldstein-Street: 425-339-3439; jake.goldstein-street@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @GoldsteinStreet.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.