DARRINGTON — You’d think that kids in a town surrounded by forests and rivers would know every trail around, know a Douglas fir from a Western hemlock, know how to paddle a canoe.

That’s not always so. Which is why the Glacier Peak Institute exists. The local nonprofit collaborates with the Darrington School District to integrate outdoor and environmental lessons into subjects from science to physical education, in and out of the classroom.

“I think we are opening their eyes,” said Daniel Dusenberry, Glacier Peak’s program support coordinator. He has taught youngsters to make mushroom stir fry, catch bugs in nets, make natural dyes and put up a tent.

“We had a camping trip last year,” he said. “For all but two of the 12 kids, it was their first time camping, the first time ever not being home at night.”

The institute’s most consistent school contact with students in first through fifth grade. For one period a week, Glacier Peak staff teach lessons in the campus greenhouse or the nearby woods.

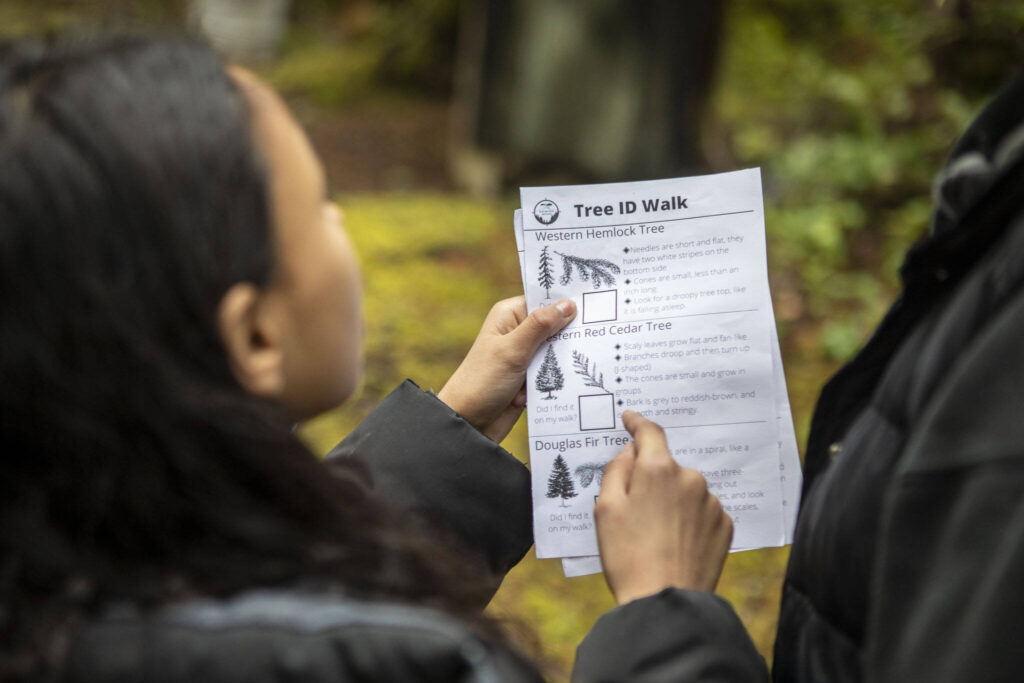

One mild February day, the objective was tree identification. Wriggly third graders listened as staffers Hannah Dreesbach and Bailey Huff laid out ground rules. There were tough rules, like don’t take anything from the forest, even pretty leaves. And there was the most important one: “Have fun!” On hearing that, the students dashed full throttle across athletic fields toward the woods.

After students identified six tree species, Dreesbach asked them to pick a favorite. The Big Leaf Maple was top-rated. Why? Holding up a leaf as wide as her head, one girl answered with a tone of isn’t-it-obvious? “Because it’s BIG!”

Glacier Peak’s roots lie in something that had been obvious to Darrington grownups for decades, and painfully so: The timber industry that supported the community was in decline. Jobs were disappearing, and with them, young people’s connection to the place and their reasons to return home after venturing into the world.

In the 1990s, Darrington Mayor Dan Rankin said a group of concerned residents drafted a proposal for outdoor and career-focused programs and took it to school officials. Their response: Fantastic idea, but we can’t afford it. Enrollment was dropping and state funding is based on enrollment. There wasn’t enough time and staff to design a program and get it approved by state education officials. The plan was shelved.

Then in March 2014, the deadliest landslide in U.S. history killed 43 of Darrington’s neighbors in nearby Oso. Highway 530, the main road out of town, was buried.

“That was our second disaster, after economic decline,” said Oak Rankin, who is Dan’s nephew and Glacier Peak’s executive director.

Oak Rankin graduated from Darrington High in 2001 and left for college. He majored in political science and environmental studies, won a Fulbright scholarship and taught English in Brazil. Then he worked for the U.S. Forest Service and Park Service. He also worked as a logger and outdoor guide.

He was guiding a Colorado rafting trip when the landslide crushed homes and spirits. He emerged from the Grand Canyon three weeks later, wondering if there was still any way he could help. His uncle Dan said: “You can come back here and make a difference.”

The long-shelved education plan was dusted off.

There was still no school district money to implement it, so the idea of a nonprofit institute emerged. Known locally as GPI, Glacier Peak is based in a rental that may be the oldest building in town but isn’t the fanciest. The organization has been successful at landing state grants from the No Child Left Inside and Outdoor Learning programs. It relies heavily on AmeriCorps volunteers.

“Only a few private foundations and organizations have come forward to help us with development,” Oak Rankin said.

The 2022 budget was $350,000. Glacier Peak hopes to more than double that this year using still-available pandemic stimulus dollars, but they have yet to come through.

Without funding for administrative staff, Rankin has become a jack of all trades and then some. His day can include coaching outdoor activities, coordinating with partners, driving a trailer, writing hiring policies, negotiating contracts. And of course, applying for grants. Rankin said he’s had to get more comfortable with asking for help — no small thing in a town where self-reliance is prized.

Fundraising includes the annual gear drive to build Glacier Peak’s inventory of outdoor recreation and gardening equipment. Rankin said boots and backpacks, to say nothing of mountain bikes, can be hard for kids to come by, especially for those who come to school with holes in their shoes.

“The outdoors is seen as having this high price of entry,” said Dusenberry, the program coordinator. While a lot of kids are uninterested in outdoor activities, he said, those who do venture out “just absolutely love to be there.”

Glacier Peak’s size limits its offerings, inside and outside of the classroom. Staff would like to see more teens involved and a return to middle school lessons that fell off during the pandemic. But its current efforts draw praise from Tracy Franke, who serves as both elementary school principal and superintendent of the 448-student district. Faculty members agree.

“Glacier Peak Institute has been an incredible asset to our school and community,” physical education teacher Gavin Gladsjo said.

He ticks off a long list of ways the institute has helped the PE program. Among them, teaching Leave No Trace principles to fourth and fifth graders. Providing 10 Essentials kits to promote outdoor safety. Showing middle and high school students how to collect pinecones as a way of making money. Securing grants to build an outdoor education classroom. Helping fund first-aid certification for students in health classes.

Mayor Rankin, who chairs Glacier Peak’s board of directors, sees plenty of room for the institute to grow. His dream is securing state accreditation for technical courses, such as wood shop where students can both learn and apply math. It’s critical to introduce kids in fourth through seventh grade to potential careers, he said.

“They need to know there are jobs in the woods, in the streams, in biology,” Dan Rankin said.

“Glacier Peak is doing phenomenal work out there,” he added. “But we’ve only scratched the surface of what the possibilities are.”

Julie Titone is an Everett writer who can be reached at julietitone@icloud.com. Her stories are supported by The Herald’s Environmental and Climate Reporting Fund.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.