EDMONDS — A white cartoon rabbit with his hand raised in a perpetual wave beckons northbound drivers crossing into Snohomish County on Highway 99.

The neon sign marks Harvey’s Lounge, a local pub that offers billiards, pull tabs and beers.

Set back the clock about 90 years, and customers could still find a stiff drink and chance to gamble here — with a few differences. The hare would be gone, not yet relevant to a tavern known in the 1920s and ’30s as Albright’s Cafe. The pool tables would be absent, swapped for a large dance floor and stage fit for a jazz ensemble. And the betting and drinking would be criminal, outlawed by prohibition and other early temperance laws.

Local prohibition historian Brad Holden said the pub is one “physical remnant” of a rich history of roadside inns, taverns and dance halls — commonly known as roadhouses — that operated along Highway 99 and Bothell-Everett Highway. Centers for sin, dozens of roadhouses popped up in Snohomish County in the 1920s. Only a few still stand today.

Their stories live on in “Lost Roadhouses of Seattle,” a new book by Holden and fellow historian Peter Blecha. Published this August, the book documents almost 60 of Puget Sound’s “most decadent and debaucherous nightclubs,” many of which were actually located north of the Emerald City, in Snohomish County.

“The Highway 99 roadhouses were kind of the seediest roadhouses in the area,” Holden said. “They were the most notorious because a lot of them offered gambling in addition to illegal drinking. And there was a lot of prostitution, too.”

‘Countrified’ clientele

The story of Edmonds roadhouses begins in Seattle, the “epicenter of vice” from the 1890s to 1910s, Holden said.

“Pretty much every corner on every block was a saloon or a brothel or a gambling parlor or a boxhouse, billiards rooms,” Holden said. “It was quite the place back then.”

A local temperance movement rose up, but due to “corruption” of local officials who often drank at the speakeasies alongside the owners, it did little to stop the boozy behavior, Holden said. It wasn’t until the mid-1920s when the Seattle police and King County sheriff’s deputies really “clamped down,” he said.

Around the same time, new roads were built to accommodate the rise of automobiles and connect Seattle and Everett. Two of the earliest roads, Highway 99 and Bothell-Everett Highway, helped push illicit conduct north. Saloon and speakeasy owners opened on the “other side of the county line” to escape Seattle law enforcement, Holden said.

“The highways at the time were really remote. They looked nothing like they do now,” he said. “They were really wooded, so it was easy to open these new places up along these highways and be out of the beaten path.”

Where Seattle speakeasies catered to the affluent — including Seattle Mayor Edwin Brown, who frequented bootlegging businessman Doc Hamilton’s Barbecue Pit, one of the city’s most popular speakeasies — the northern joints were usually “countrified” by backwoods customers, Blecha said.

“This is where you got those brawls going on, the huge headlines … people fighting the cops,” Blecha said. “It was just a different clientele out there.”

Despite police raids, the Snohomish County roadhouses persisted.

“The owners would be put in Snohomish County Jail,” Holden said, “but as soon as they would get out, they’d just go right back to business.”

Even after Prohibition ended in 1933, roadhouses continued to skirt the law. When the state’s newly founded Liquor Control Board barred restaurants and taverns from selling hard alcohol, while limiting beer and wine to 3.2% alcohol by volume, many roadhouses converted into “bottle clubs”

“They just started allowing customers to bring in their own bottles of booze,” Holden said. “They pretended to look the other way, but they knew what was going on. In fact, they offered them mixers and pitchers and devices so they could just mix their own cocktails.”

The accoutrements were usually delivered by tray and included in the cover charge, Holden said. Customers would keep their liquor bottles on the floor and “discreetly” fix their stiff drinks.

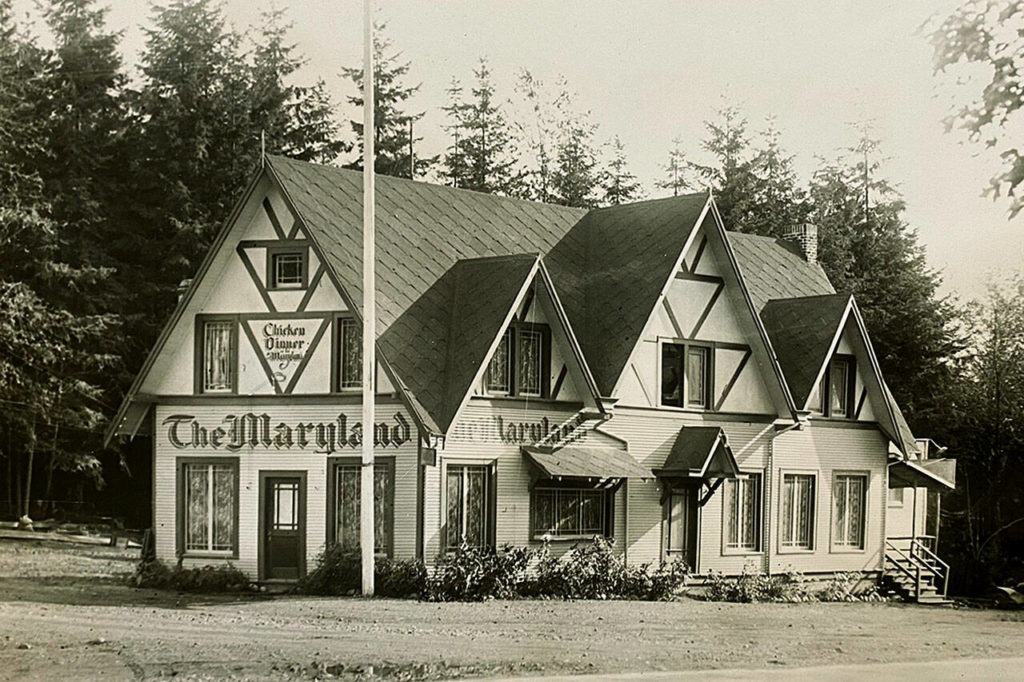

Each roadhouse offered its own personality. Some were large and ornate, like The Maryland, a Bavarian-style building with three gables prominent on the front, located across the street from Albright’s. Today, The Maryland is gone, replaced by a Jack in the Box.

Other taverns resembled roadside shacks, like the Jungle Temple No. 2.

Blecha said he especially likes George McKenzie’s Bungalow Inn, a roadhouse near Silver Lake.

“I get a kick out of that one, because there it is, way out there on a lake, yet the marketing of the thing was an attempt to portray a glamorous (business),” Blecha said. “It’s not a log cabin like a couple of these places. It was the place that was bragging in its advertising about having an 8,000-square-foot maple dance floor, one of the biggest in the area.”

No matter the appearance or amenities, in all of the roadhouses, drinking and skulduggery ran rampant.

‘Suddenly the place would be on fire’

Jazz and big band musicians set the soundtrack for raucous evenings. The music is a big part of what makes the roadhouses historically important, Holden said.

Many roadhouse-era dives boasted big stages and dance floors. Regional stars headlined, including Oscar Holden, dubbed the Patriarch of Seattle Jazz. Brad Holden — no relation, he said — found evidence that the jazz pianist and clarinetist made appearances at the Jungle Temple No. 2.

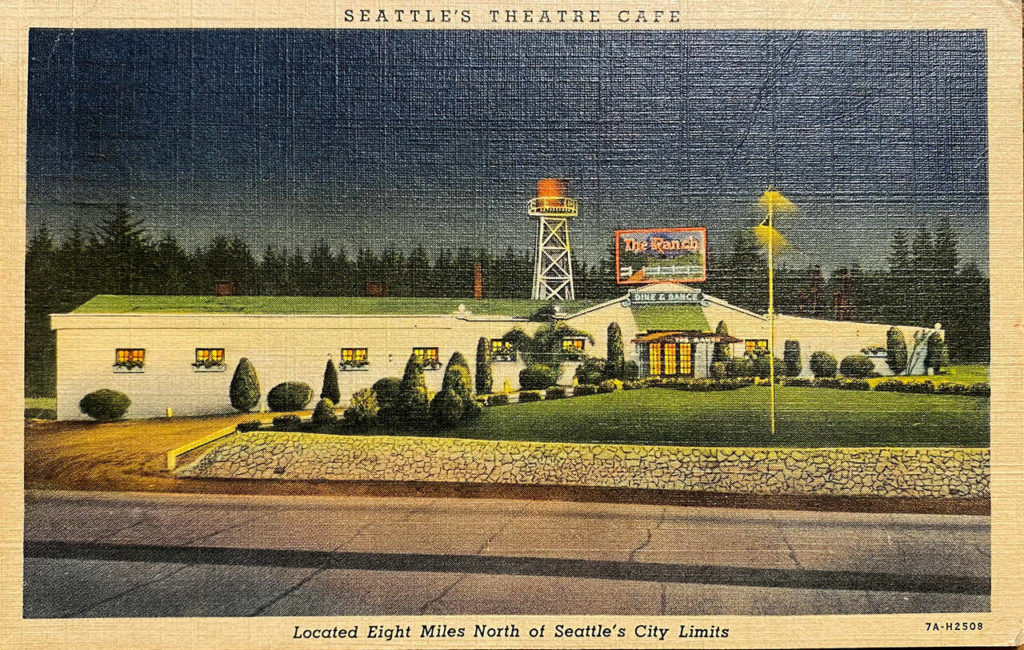

“Despite its ramshackle appearance, the Jungle Temple No. 2 (located on Hwy. 99 in Edmonds where Ranch 99 now sits) was one of the musical epicenters of the local roadhouse scene…” Holden wrote in a July tweet.

Customers would drive up to Edmonds in their jalopies, head to the bar to order drinks and spend the night dancing, Holden said. Most of the music was “first-generation boogie woogie and ragtime jazz,” Blecha said.

Ironically, music led to some of the roadhouses’ downfall. In the 1950s and ’60s, rock ’n’ roll rose up as the hot new music trend. Roadhouses that continued to host jazz artists saw their crowds age and shrink.

Liquor laws also loosened up, allowing for the sale of hard alcohol and pushing once-forbidden culture into the mainstream.

“(Roadhouses) weren’t as popular. It was mostly the older people who were going out to those places that were still in existence,” Holden said. “They weren’t really focused on the crazy vice aspect of it (anymore). It was more going out and dancing to some wholesome music.”

Some speakeasies were converted to legal pubs. Such was the fate of Carl Melby’s Echo Lake Tavern. After its namesake owner died 1942, the building operated as a “number of different taverns.” Today the building hosts Woody’s Tavern, a modern watering hole that gives a nod to its rowdy origins. A mural on the outside of the building shows what it looked like in the ’20s. Historic photos and newspaper clippings on the interior walls retell the story of Melby’s bootlegging glory days.

Woody’s current owner Summer Marez said for years she has heard stories about when the bar was a speakeasy. Marez and her bar manager have researched the history for photo displays inside.

“I think people like to see what (used) to be present in the same exact spot decades prior,” Marez wrote in and email to The Herald. “How people might have dressed or the architecture of buildings. What was here in this location before … all the cars and rush hour traffic.”

She said the exterior of the tavern hasn’t changed much since Melby owned it, but the inside has “been updated to a degree.” Years ago, there would have been a false floor and trap door on the main level that was used bring alcohol into the bar in the evenings — and to conceal it during the day.

“Carl Melby had been arrested on more than a few occasions for transporting alcohol during prohibition,” Marez wrote. “He used to run Canadian whiskey and other alcohol from BC down the coast on boats to Woody’s via Richmond Beach.”

Albright’s Cafe reopened as Harvey’s Tavern in 1949. The business probably ran as a roadhouse from the late 1920s to the mid-1930s, but “it’s entirely possible Albright’s existed as Albright’s up until 1949,” Holden said. Official records weren’t always scrupulous, for obvious reasons.

Other roadhosues changed hands and business models several times over. The Olympic Tavern, a roadhouse about a block west of Highway 99 on modern-day 220th Street SW, closed after a 1927 New Year’s Eve raid. It has since operated as a hospital, hunting lodge, brothel, dog training business and church youth center. The building still stands today, now a home.

Many more roadhouses “mysteriously” burnt down, a phenomenon Holden has a hunch about.

“What would happen is these places would get raided. The owners would basically know, ‘I’m not going to be able to continue operating,’” Holden said. “And then suddenly the place would be on fire, probably to collect insurance money, to end things and get a paycheck for it.”

All that’s left of most local roadhouses are physical mementos, like matchbooks, postcards and photos. Holden said he learned about a number of the clubs on Highway 99 from local historian Betty Lou Gaeng, who grew up on the route when it was still a rural road. Her father was a sheriff’s deputy who raided some of the speakeasies. She shared with Holden stories of collecting leftover booze bottles after a “jumping” Saturday night at The Maryland. She and her siblings would turn them in for change.

“I was able to consult her and get a lot of information to fill in the blanks,” Holden said. “But it took a lot of research.”

‘Still surprises’

Holden and Blecha continue to uncover the stories of past roadhouses. About a week ago, Blecha discovered two more dance halls that used to sit along the Bothell-Everett Highway. The Rebels Inn would have fallen into the Southern-themed taverns covered in the book, while The Ship offered dancing and drinking on the deck of a vessel docked in Kenmore.

“There are still surprises to be had as we stumble across new clues,” Blecha said.

“The Lost Roadhouses of Seattle” is what Holden calls a “COVID project,” born out of extra time at home and a shared love of local roadhouse history. He and Blecha spent almost two years compiling research and editing it into a cohesive text.

Holden said learning about the local lore has helped him appreciate a good dive bar and “micro-history” on a deeper level.

“It’s my neighborhood history, almost,” said Holden, who used to live two blocks down from the the former Olympic Tavern. “And it’s a cool part of of neighborhood history. … So that’s why it was a joy to write this book and chronicle it for the first time.”

The duo will host a book release 2 to 5 p.m. Saturday at the Shanty Tavern on Lake City Way, a former roadhouse site covered in the book.

“Lost Roadhouses of Seattle” is available for purchase at local bookstores and on Amazon.

Mallory Gruben is a Report for America corps member who writes about education for The Daily Herald.

Mallory Gruben: 425-339-3035; mallory.gruben@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @MalloryGruben.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.