MUKILTEO — A century and a half after 82 tribal leaders gathered in Mukilteo to sign the Treaty of Point Elliott, some of their descendants are still asking the federal government to recognize them as Indigenous people.

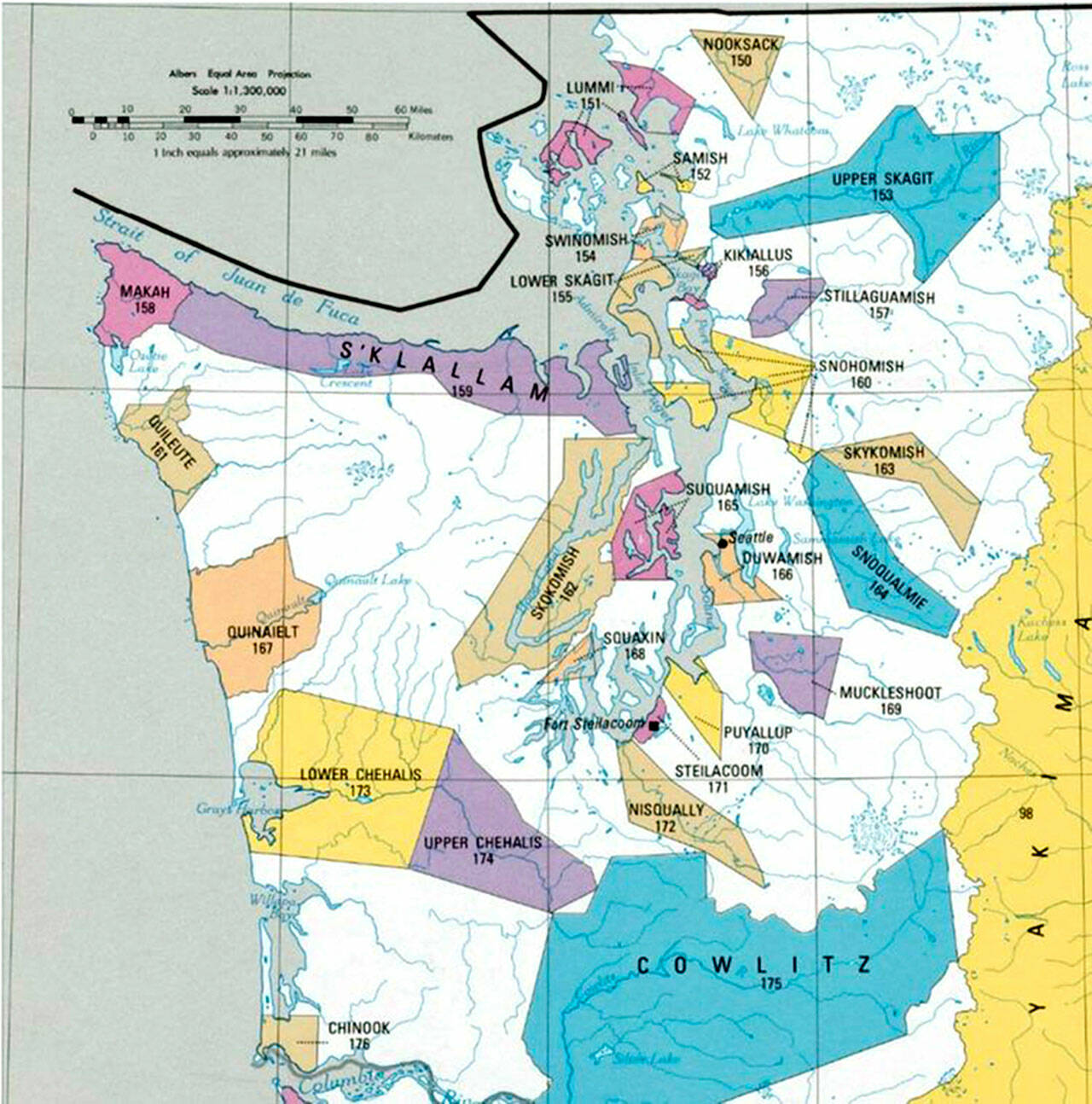

The Tulalip Reservation became the permanent lands of the Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skykomish and other allied tribes. It was first intended to be the permanent government-assigned home for the Point Elliott treaty tribes. Instead, other temporary reserves established in the treaty — Port Madison (Suquamish), Swinomish and Lummi — became permanent reservations.

The first signature on the treaty came from a Duwamish and Suquamish tribal leader: Chief Seattle.

Yet a designated reservation was never established for the Duwamish people, whose traditional land sits between Puget Sound and Lake Washington, according to a lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court in Seattle earlier this month.

The U.S. Department of the Interior “recommended for several years that the Duwamish Tribe be allotted a separate reservation ‘on or near the lake fork of the D’Wamish river,’ in present-day Renton on or near the Black River,” the lawsuit states. But settlers successfully petitioned against its creation.

“The Duwamish, we’re a treaty tribe,” said tribal council member Desiree Fagan. “… When I was younger, that was really confusing to me. … Like, we’re not a real tribe?”

Now they’re suing the Department of the Interior, alleging that while Congress has recognized the tribe’s treaty rights, they have been refused federal recognition.

They argue the department discriminated against the tribe on the basis of sex, basing prior decisions on data from the 1900s that largely excluded the tribe’s women and their mixed-race children. Many Duwamish women married white settlers. They also allege the tribe was “undeniably treated differently than similarly-situated tribes that primarily descend from Indian men, which violates the Tribe’s guarantee of equal protection under the laws.”

The Duwamish first brought suit against the government in 1925. In 1978, they filed their first petition for recognition. They’ve been working for acknowledgement since.

“The Department of Interior apparently contends that the Duwamish Tribe that signed the Treaty of Point Elliott has somehow ceased to exist,” the lawsuit states. “That contention not only conflicts with the historical record, it also conflicts with determinations made by other federal authorities.”

Some Duwamish tribal members are enrolled in the Muckleshoot Tribe, Fagan said. As part of a federally recognized tribe like the Muckleshoot, members gain access to tribal health care, education and economic programs. Those “benefits” were guaranteed in treaties.

The people who didn’t go to the reservations lost access to those resources. The Duwamish’s 600 members are the descendants of those people, Fagan said.

“These things called reserves aren’t really nations that belong to the people that are living on it,” Duwamish Tribal Councilmember Ken Workman said, “but, rather, they are land that the government has set aside and told people if you move there, and we will take care of you, and we will recognize you as a person.”

“If we were to be federally recognized our three priorities are health, welfare and education for our people,” Fagan said. They want the treaty rights that they were denied.

Many Duwamish people just want to be seen as equal. Or seen at all.

“What it would mean to be recognized would be that I would be able to move around in Native circles,” Workman said. “There are people that are federally recognized who say, ‘Well, you’re not a real Indian. … And and that hurts a lot as well.”

‘Let the Natives fight it out’

Copies of each page of the Point Elliott treaty are laid out under a glass panel in the Hibulb Cultural Center on the Tulalip Reservation.

The yellowed document calls for the signatories to move from their expansive traditional homelands to small parcels of land: reservations. The word Tulalip comes from the Lushootseed word dxʷlilap, meaning “far to the end,” according to the Hibulb center. It describes how canoes had to keep a wide berth around the southern sandbar. It was never, historically, the name of a tribe.

The Duwamish are not the first group of descendants of the signatories to the 1855 treaty who have fought for recognition.

Federally recognized tribes have often intervened in efforts by smaller tribes or bands to gain recognition. In the case of the Snoqualmie tribe’s appeal for recognition, the Tulalip Tribes were the primary opponents. Tulalip lawyers argued the Snoqualmie people splintered from the tribes, and some Snoqualmie descendants enrolled with the Tulalip Tribes.

The Snoqualmie people ultimately gained federal recognition in 1999.

The Stillaguamish people remained on ancestral land and lived mostly undisturbed until the 1870s, said Tracey Boser, a Stillaguamish elder and cultural resource specialist. They, too, were signatories to the Point Elliott Treaty and ordered to go to Tulalip.

But not everyone did.

Esther Ross, a former tribal chair, spent decades fighting for the Stillaguamish to be federally recognized. In 1976 the stuləgʷábš, or People of the River, were federally recognized as the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians.

In 2014, the Stillaguamish Tribe was finally granted a reservation: about 64 acres of land west of Arlington.

Snohomish Tribal Chair Mike Evans says it has been a similar story for his tribe’s hundreds of members, except they still haven’t received recognition. In a 2004 appeal, the tribe argued poor living conditions in the early years of the Tulalip Indian Reservation kept many Snohomish people from living there.

In 2008, the Snohomish Tribe filed another lawsuit in U.S. District Court to overturn a decision that denied it federal recognition.

The Tulalip Tribes became successors to the Snohomish Tribe, said Teri Gobin, chair of the Tulalip Tribes.

As for those who are fighting for federal recognition, “they are descendants, they are Native,” Gobin said. But it’s complicated, she said.

“It’s a tough situation,” she said. “We know they have Indian blood, but we have to protect our treaty rights.”

Most of the policies causing present-day disagreements between tribal nations are a result of federal policies.

The government decided “to let the Natives fight it out,” Gobin said. “We have to protect what we have left.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.