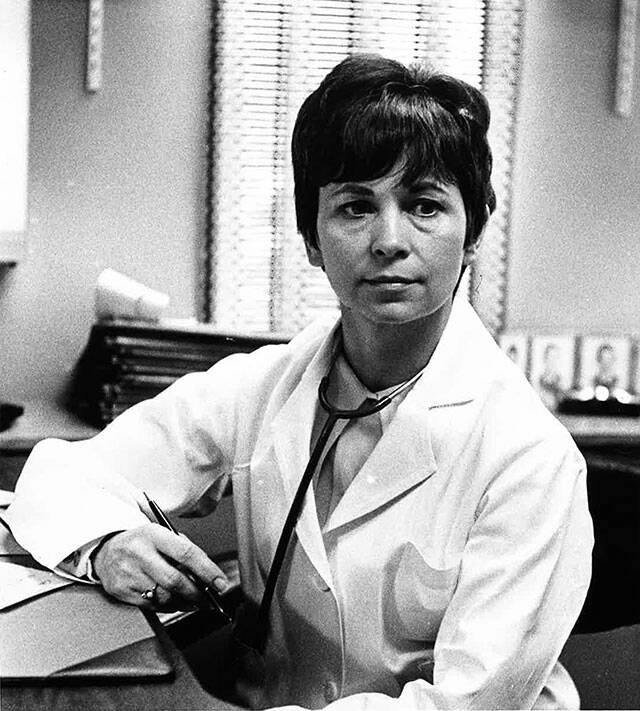

EVERETT — In 1924, the Everett Clinic was founded by four physicians. All men. It would be another 35 years until the clinic hired a woman as a physician. Her name was Lucille “Lucy” (Winkler) Mason.

Mason started work at the clinic in 1959. She recalled how many of her older male colleagues at the time were skeptical of her ability.

“Perhaps in the beginning they looked on me as a mascot that would be nice to have around if I behaved. But I earned their respect,” Mason said in a 1995 interview with The Daily Herald.

Mason entered the medical field at a time when women were a rarity among doctors. She specialized in family medicine and treated multiple generations of patients in Snohomish County.

On Aug. 13, Mason died of complications related to Parkinson’s disease. She was 92. Mason was preceded in death by her husband in 1993. She’s survived by four children and 10 grandchildren.

Aside from treating patients, Mason spoke publicly on women’s health at local workshops and “increased the transparency and the dialogue on things that back then were kind of very hush-hush, and weren’t talked about openly,” said her daughter, Linda Mason Wilgis, of Seattle.

Mason visited middle and high schools to speak on sex ed. A Herald article on Mason’s retirement described her as “a fearless straight arrow on a subject that was essentially taboo for general discussion in the ‘Leave It to Beaver’ years.”

Judy Matheson was a former patient of Mason’s. She met the doctor in 1967. As a shy 20-year-old, Matheson felt more comfortable seeing a woman doctor.

“I always called her my ‘no-nonsense doctor,’” Matheson said. “I went in and Lucy told me like it was. She would sit and listen to everything I had to say like we were old friends.”

One time Matheson saw Dr. Mason for what she believed was a spider bite. The doctor told her bluntly: “‘Judy, you have shingles,’” Matheson recalled.

The two remained friends after Mason’s retirement in 1995. She often visited her patient’s shop, J. Matheson’s Gifts, Kitchen & Gourmet, in downtown Everett.

Dr. Jim Finley remembers meeting Mason in 1973 when he joined the Everett Clinic. He joked he never received a complaint about her in his 18 years as medical director.

“Her patients absolutely loved her,” he said, and many followed Mason when she opened a private practice in 1983.

Finley recalled how he affectionately told his colleague “I Love Lucy,” a reference to the sitcom named after actress Lucille Ball.

“She was an interesting, colorful character,” he said.

Mason wasn’t just the clinic’s first, but its only woman working as a physician until pediatrician Katherine Runyon was hired in 1981. Mason Wilgis said it’s hard for people under age 45 to understand just how unusual it was for a woman to be a doctor back then. In grade school, a teacher asked Mason Wilgis what her father did for a living.

“I told her that both of my parents were doctors,” Mason Wilgis said. “And she said, ‘No dear, you mean your mother is a nurse.’ And I said, ‘No, she’s a doctor.’ And that was just inconceivable to her, and probably even just unlikely to have a mom working outside the home at all.”

Mason was born on Nov. 15, 1929, in Chicago, Illinois, the youngest of five kids, according to her obituary. She grew up amid the Great Depression.

She decided to become a doctor at age 12, after her sister’s appendix got infected and had to be removed. Mason was one of four women in her medical school class at Loyola University Chicago.

“My mom had a lot of confidence in herself,” Mason Wilgis said. “There were very few things that she thought she couldn’t do.”

In 1954, Mason married Dr. Gene Mason, also a physician. The two first met in a Chicago morgue and eloped six weeks later. The couple eventually relocated to Washington.

Mason Wilgis said her parents were adventurous and made the most of their time outside of work. They were avid boaters and took many trips to the San Juan and Gulf islands. Mason’s obituary noted her passion for crabbing, how she was known for hosting a “legendary Thanksgiving brunch” and was rarely without a book by her side. Mason Wilgis described her mother as a risk-taker. Several times, Mason woke her children up on Fourth of July by throwing lit fireworks into their bedroom.

“As a doctor, you think she’d be maybe cautious about things, or conservative, but she had this side that was just very spirited and exuberant,” Mason Wilgis said.

Mason Wilgis’ father was a world-class mountaineer who climbed some of the tallest peaks on four continents, according to his obituary. The family joined in on several of his expeditions, including a climb of Mount Kilimanjaro. The couple’s youngest daughter Lori got her picture featured in Sports Illustrated for being the youngest person to have climbed the mountain at the time.

In 1972, the Mason family relocated to Tanzania in east Africa. There, Mason’s husband lectured on anesthesiology at a university and she worked for the U.S. Embassy, which had no doctor until she arrived. She treated Americans for ailments like malaria. She also performed surgeries. The family returned stateside two years later, but their love of Africa remained for a lifetime.

When she retired, Mason received an outpouring of letters, cards and notes from patients telling her how much she meant to them.

“I’ve always loved what I did,” Mason told The Herald. Letters and phone calls “brought home to me how much a doctor can touch people’s lives.”

Eric Schucht: 425-339-3477; eric.schucht@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @EricSchucht.

Jacqueline Allison: 425-339-3434; jacqueline.allison@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @jacq_allison.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.