EVERETT — It has now been three years since the city of Everett took on the challenge of eliminating growing budget deficits.

The city enacted a series of tax hikes and cuts to some services, bridging a $13.1 million gap in the 2015 budget and reducing deficits in the years that followed.

The city still anticipates its expenses will outstrip its revenues for some years to come.

That will be a major challenge for whoever becomes Everett’s next mayor.

“When the economy gets a little less robust, and it will, we need to make sure our spending rate doesn’t exceed our revenue in a down economy,” Mayor Ray Stephanson said.

Complicating matters is the trade-off between continued belt-tightening and spending to meet critical needs.

The Everett Police Department has 18 open police officer positions that it’s been trying to fill as quickly as possible. There’s a chronic opiate problem across Snohomish County and gang violence is spiking.

But 48 officers have retired in the past three years, with another two scheduled to leave by the end of June. Hiring has barely been able to keep pace.

While services haven’t been hit too hard, the officers have been squeezed by scheduling and limited when it comes to taking time off.

In May, the City Council approved a hiring bonus for officers brought over from other police agencies in the hopes it would help fill the ranks faster.

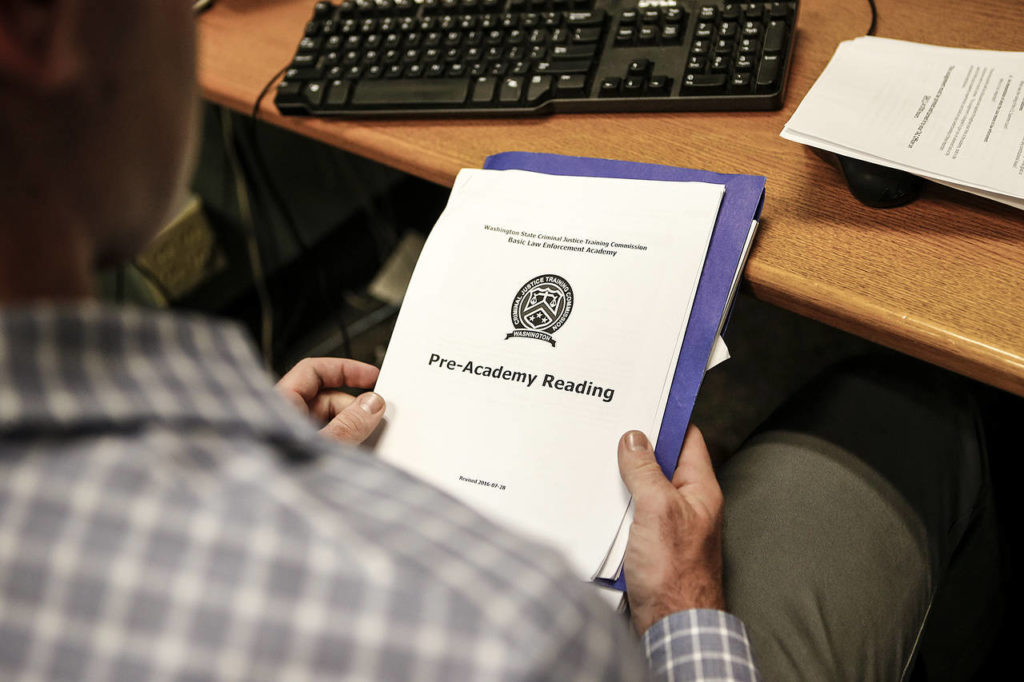

Officer Ora Evans, who was sworn in June 14, was a lateral hire from the Vancouver Police Department. She moved north after a classmate from the academy convinced her to visit Everett.

“It felt like home,” Evans said, “which was important, because Vancouver felt like home, too.”

She became the 51st officer hired by the city in the past three years. Because she was a lateral hire, she started field training without having to go back to the state Law Enforcement Academy.

Hiring affects the city’s finances because when jobs go unfilled, the money set aside for those salaries has helped balance the budget.

This isn’t a new practice. With a budgeted staff size of nearly 1,200 full-time positions at the city, there are always a certain number of vacancies.

It can add up to a lot of money. At the end of 2016, the city balanced its budget in large part due to carrying forward $6.2 million in unspent salaries.

As of June 1, there were 32 vacant positions in the city government, including in the police department. Based on a newly hired officer’s starting salary of $68,052 per year, filling those 18 officer slots means the city would have about $1.2 million less to help balance its budget.

Filling all 32 positions at once is unlikely, but if it were to happen, the cumulative impact could reach up to $3 million.

Earlier this year, the City Council moved about $6.4 million into a reserve fund to pay for some expenses in 2018, essentially eliminating the projected deficit in advance.

“Honestly, having those vacancies has given us the ability to prepay things like insurance and retirements,” Stephanson said.

“If we continue to spend responsibly, our ability to balance the budget will be every bit as successful as it has been,” he said.

That doesn’t mean it won’t be a challenge.

Police hiring is expected to pick up as retirements taper off in the near future, Officer Aaron Snell said.

Officers hired from other departments, such as Evans, have higher starting salaries, but require less training and get out on patrol sooner, so it’s a worthwhile expense.

“They bring with them a wealth of experience,” Snell said.

Offsetting those newly filled positions will require savings elsewhere.

“As we fill those positions going forward it will be much harder to balance that budget and resolve the deficit,” said Susy Haugen, the city’s treasurer.

Rolling deficits

Everett’s structural imbalance can be traced back to the 2001 passage of Initiative 747, which prevented local governments from raising property tax by more than 1 percent without a public vote. The initiative was found to be unconstitutional, but the Legislature later enacted its provisions into law.

The hit to the city government’s finances was compounded by the multi-year recession, in which property values declined, sales and business tax collections plummeted and construction activity slowed and sometimes stopped.

By 2014, the economy was rebounding, and revenue coming into the city coffers was growing at 2.3 percent per year. At the same time, expenses were growing at 4.1 percent annually.

“We were recovering from some pretty dark days,” Haugen said.

If nothing had been done, Everett’s projected 2015 deficit of $13.1 million was forecast to grow to $21.4 million by 2018.

The city took several steps that year to balance the 2015 budget and shrink the projected deficits for years ahead.

The biggest increase in revenues came from increasing utility taxes over the following years and adding new taxes on cable TV and garbage collection. As a result, in 2016 the city collected $4.6 million more than if the city had not raised the taxes.

In addition, the $20 car tab fee has provided about $1.5 million in new revenue per year to help pay for street repairs.

On the expense side, the city cut 15 full-time positions from the budget, most of them vacant, saving $1.4 million. The city also eliminated the library outreach program and bookmobile and streamlined contracting for smaller jobs, among other measures.

The biggest reduction in spending came from the longer process of negotiating union contracts, especially for police and firefighters, so they’d pay more for their health care premiums.

Police officers now pay 10 percent of their health insurance costs, the same as most other city employees. Beforehand they hadn’t had to pay anything. The same was true with the city firefighters, who now pay 5 percent of their medical premium following an arbitrator’s ruling earlier this year. The total savings to the city from those changes is estimated to be about $1.8 million per year going forward.

Today, expenses are still outstripping revenue, but because of those earlier measures, the city is starting from a higher baseline, leading to smaller overall deficits.

Looking forward five years — the same view the original projection took — a projected budget deficit of $6.4 million in 2018 is expected to grow to $15 million by 2021.

Earlier this year, the City Council approved the transfer of about $6.4 million from the city’s general fund into a reserve fund for the coming year — essentially paying down that budget gap months in advance.

Department heads continue to review each new staff opening and work with the city administration to either fill it or reorganize the office, Haugen said. Other expenses are carefully reviewed and managed throughout the year.

“I think we’ve currently benefited from a strong economy and a strong construction environment,” Stephanson said.

“My hope is that city leaders will continue to show a lot of discipline about spending,” he said.

Unstable funding sources

There are many factors contributing to the ongoing deficits that are outside the city’s direct control. The three largest categories of tax — property, business and sales — together account for 75 percent of the city’s revenue.

Business taxes and sales taxes are notoriously volatile, rising and falling with economic fluctuations.

The largest single revenue source is property tax, which makes up about 27 percent of the city’s income.

One of the top priorities for cities and counties across the state is to get the Legislature to lift the 1 percent cap on property tax increases. If not that, they want to at least be able to factor in the inflation rate so that local government doesn’t continually lose ground.

The annual inflation rate was about 2.2 percent for the year ending in April 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, but many city leaders say that some costs, especially construction, are rising faster.

Growth in Everett is expected to increase the total property tax collections an average of 1.7 percent annually through 2021. That’s a combination of the city taking the maximum 1 percent increase each year, plus the effect of new construction in the city.

Business and occupation tax, which is levied on businesses’ gross receipts and accounts for more than 60 percent of all business taxes, is expected to be mostly flat over the next five years, according to the city’s budget forecast. Sales tax income is expected to grow by a comparatively robust 1.9 percent per year.

All taxes on business together account for 28 percent of city revenue, while sales tax accounts for another 20 percent.

The hope is that city income eventually will rise faster than spending and inflation and that will erase the deficit. It will take more work in the coming years, however.

“Local government is sort of at the bottom of the food chain,” Stephanson said.

Stephanson said that between the Trump administration and the challenges faced by the state Legislature, there is still an uncertain financial environment for the city.

He remains optimistic that Everett will continue to look for better and smarter ways to do business.

“I think we’ve got the discipline, we’ve got the mindset to manage our way through it,” Stephanson said.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.